My journey from aspiring to be a chicken rice seller to becoming a teacher and igniting sparks in children

Primary One. I’m not too sure what you remember about that time of your life other, other than having to hold your partner’s hands when moving from place to place, being called out for talking in class, or simply adapting to an institutionalised environment.

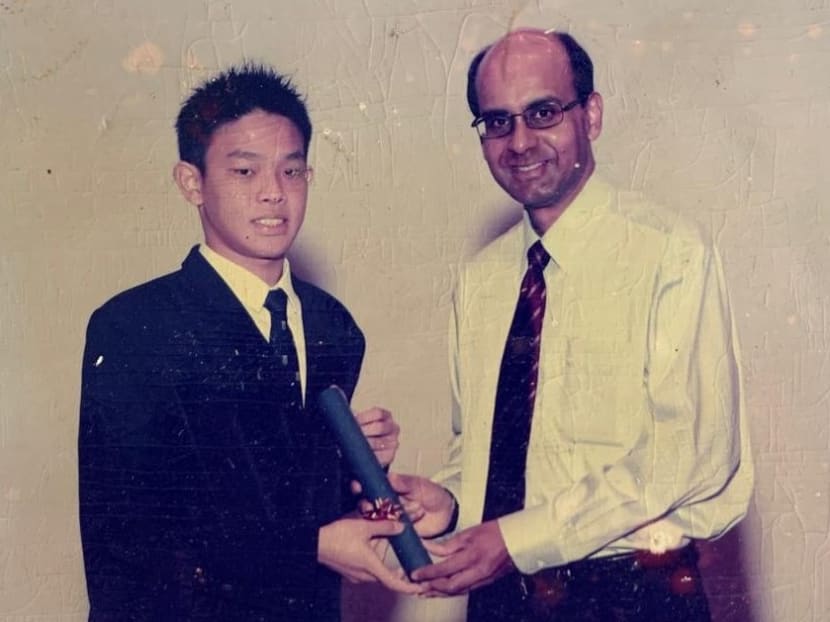

David Hoe taught in a school for three and half years before transferring to the Education Ministry headquarters to support work areas relating to disadvantaged students.

Primary One.

I’m not too sure what you remember about that time of your life other, other than having to hold your partner’s hands when moving from place to place, being called out for talking in class, or simply adapting to an institutionalised environment.

But for me, the most impressionable memory in Primary One was Art lesson.

Perhaps you recall a time when the teacher asked you to draw your ambitions with crayons on an A3 drawing block with the prompt “When I grow up, I want to be …”.

Most of my peers would end up with illustrations of lawyers, doctors, teachers, pilots, firemen, and policemen. Maybe the odd astronaut or soldier.

My teacher was flabbergasted when she saw my caricature of a chicken rice shop uncle — replete with the prototypical “Good Morning” towel wrapped around his neck.

I couldn’t understand the incredulous look on her face, coupled with her beseeching me to take more effort to think about my aspirations in life (that align my goals with social desirability or acceptability).

I genuinely thought being a chicken rice seller was perfectly acceptable in my world.

After my divorced mum became completely blind after a failed cataract operation, I spent much of my childhood selling tissue paper and tidbits with her to support ourselves.

While others traversed playgrounds in the common spaces, I became familiar with a host of hawker centres and kopitiams as my mother and I relied on the grace of diners to tide us through financially.

In the midst of my formative years, two of my observations culminated in my chicken rice uncle aspiration.

First, I realised that most chicken rice stores back then sold their gastronomic offerings for S$2 to S$2.50 a plate. And a plate comprised just a few slices of meat heaped on top of aromatic rice.

Second, living in a rental public housing unit meant that air-conditioning was an unattainable reality.

To beat the heat, my mother and I would seek refuge at the nearest NTUC Fairprice. Every so often, I would literally dip my head into the freezers.

I soon realised a whole frozen chicken cost less than S$5. And given how it seemed a whole chicken could well be apportioned into numerous plates of chicken rice, the younger me concluded that chicken rice uncles would have made fortunes.

And hence I viewed chicken rice as the solution to break out of poverty and embrace riches.

Fast forward six years. It wasn’t surprising that I landed up in the Normal Technical stream in secondary school with a dismal 110 T-score for my Primary School Leaving Examination.

I was devoid of focus, mentorship and purpose, and so my primary school years were a mere blur.

Like many Normal Technical students, I struggled academically.

A significant portion of each lesson would entail the teacher telling us off. While feeling remorseful, some of us were secretly happy because this meant less homework for us as the teacher would not be able to complete the topic or chapter of the day.

That was my first time paying attention during a Mathematics lesson. The class was about the area of circles and I was intrigued by the formula, πr2 because π looked visually foreign.

Midway through the lesson, I realised that if I could replace the variables with the right values, the correct answer would follow.

After a few more tries, the rare taste of success led me to believe I wasn’t that bad at Mathematics.

Success begets success.

Towards the year-end examinations, some friends asked if I could teach them Maths given my remarkable academic turnaround for the subject. I explained how I answered each question with considerable effort, and there was a sense of satisfaction when my friends understood what I shared.

It was then I thought to myself I would ditch my chicken rice uncle aspirations for teaching.

Armed with Yahoo! Search and a 56k dial-up modem, I searched “How to be a teacher in Singapore?”.

It didn’t take me too long to be disappointed. I realised that regardless of what tertiary qualifications I attained, I could never be a teacher because I would not have had a GCE O-Level certificate — a prerequisite for teachers.

But with a healthy dose of serendipity — including an appeal to the Education Minister — and opportunity, I managed to complete my O-Levels after spending two more years in secondary school.

These experiences made me realise that while most of us were not stellar in our academics and struggle to pass regardless of how hard we tried, there were still things we excelled at — like street soccer or basketball.

Perhaps, we could have excelled in other areas, but most of us lacked access to opportunities.

And accessing opportunities is largely contingent on both academic performance (which places you in schools with more resources or even having a higher chance of being selected for programmes to represent the school), and socio-economic capital of his or her family (which means access to a host of resources outside of school).

Most Normal Technical students are unfortunately not endowed with either.

As for me, I was fortunate to get into a junior college and eventually secured a teaching scholarship for my university course in economics.

After graduation, I finally got to realise my aspiration of being a teacher and taught in a school for three and half years before transferring to the Education Ministry headquarters to support work areas relating to disadvantaged students.

I am only able to be where I am today as an education officer because opportunities were serendipitously presented to me.

I recognise that the privileges I enjoy are not necessarily accessible to all.

Hence, with the networks and platforms I have attained through my unconventional life journey, I pay it forward by creating opportunities for kids to discover their talents.

One instance of this is the “I Am Talented ( IAT )” programme.

IAT reaches out to secondary school students without access to opportunities to learn skills beyond the formal curriculum such as song writing, fashion design, photography, robotics, website design and more. Each workshop is also designed with challenges, such that if the child persists, he or she will achieve something.

Given our participants’ profiles, this could potentially be their first time tasting success. Unintentionally, this success might ignite a spark within each child.

There is some truth to the old adage: “Teach a man to fish, and you will feed him for a lifetime”.

But if we can ignite a spark in every child, they will be able to discover what fish they like and be discerning in applying themselves.

What we need to see more clearly is the immense potential of every one of our youth. To unlock this potential, our youths need to have access to myriad opportunities regardless of their socio-economic or academic backgrounds.

Not everyone has access to equal opportunities. But what is true isn’t necessarily right — it shouldn’t always be like this.

My appeal to you is to create opportunities for others with less, especially if you are endowed with more.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

David Hoe is a community partnerships officer at the Ministry Of Education, a district councillor for Central Singapore Community Development Council, a council member of the National Youth Council and founder of I Am Talented. This first appeared in The Birthday Book (2020), a collection of 55 essays on the theme “Seeing Clearly”.