Navigating between a rock and a hard embrace

A key feature of Singapore’s foreign and security policy is its insistence to not “choose sides” between the United States and China.

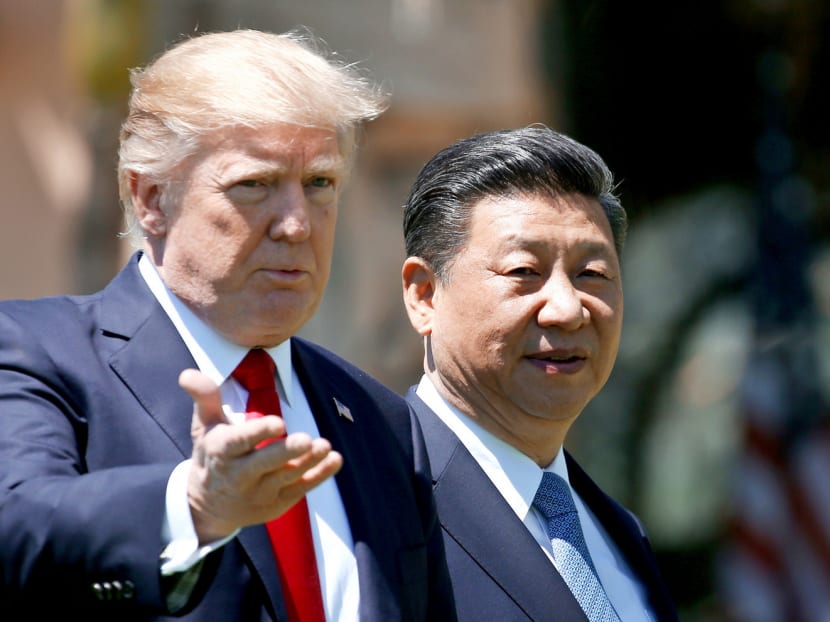

President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, in April. Singapore may have to be more active in taking steps to handle the changing nature of Sino–US relations. Photo: Reuters

A key feature of Singapore’s foreign and security policy is its insistence to not “choose sides” between the United States and China.

Singapore’s long-standing approach has so far relied on substantive overlaps in US and Chinese strategic interests. But changing strategic orientations in Beijing and Washington now see greater Chinese willingness to apply pressure to achieve its interests, along with less US attentiveness to the region.

Singapore’s traditional political space may be shrinking, as might that of its traditional partners in the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) elsewhere in the Asia Pacific. These developments may press the city-state to fundamentally recalibrate its strategic outlook.

Differing perspectives on the South China Sea territorial disputes, the nature of Singapore–US ties and Singapore’s unilateral military training in Taiwan have made Singapore a target for popular and sometimes official criticism in China.

Beijing did not invite Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong to the inaugural Belt and Road Forum, prompting speculation as to whether it was a deliberate snub. China also consistently warns Singapore “not to take sides” when it articulates positions that depart from China’s, even when such statements simply reflect Singapore’s own interests.

This suggests China’s preference for silence from Singapore on key issues.

In comparison, the past year has seen Washington’s Asia policy vacillate from opposing China’s expansive maritime claims to a lack of interest in the region.

Such events make Singapore’s external environment much more uncertain.

With Asia caught between greater US–China friction, the range of realistic options for Singapore when it comes to not choosing sides is shrinking.

Should the US effectively cede its Asian influence to China, not choosing sides may come to mean that Singapore should refrain from actions or voicing concerns that Beijing finds objectionable.

Such issues would, at best, emerge behind closed doors in bilateral settings where Beijing wields a significant advantage, given the stark power asymmetry.

Singaporean concerns would be dependent on China’s pleasure.

Singapore’s increasingly restricted options may limit it to a policy of strict neutrality that leaves both Washington and Beijing dissatisfied.

Not only might such conditions reduce Singapore’s ability to exercise initiative, it would also invite the US and China to coerce Singapore into a sympathetic position, or result in the city-state’s isolation.

One risk of Chinese dominance for Singapore over time is Finlandisation, even if many find this option unpalatable.

Singapore’s future prosperity and security would be subject to Beijing’s largesse; Singapore would have to defer to China under such an arrangement. The concept comes from Finland’s relationship with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, in which Helsinki kept all the formal trappings of sovereignty, but submitted to Moscow’s preferences on foreign and security policy.

Sovereignty is not a dichotomous quality — it can be parsed into different components, each to varying degrees. Finlandisation is arguably already happening in South-east Asia at some level, given China’s growing regional dominance.

Self-neutralisation is another possible response to greater US–China contention in Asia, but this would risk making Singapore either irrelevant or an object of competition between the two major powers.

There is, of course, the choice of picking between Washington and Beijing, but such a move introduces the danger of betting on the wrong ally, provoking major power ire, or being reduced to a major power proxy.

Another reaction could be to work with like-minded regional actors facing similar circumstances on regulating regional affairs in ways that go beyond the Asean framework. Candidates include Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and potentially Malaysia — all have long-term interests in maintaining substantive autonomy alongside regional stability, prosperity and sustainability.

Such partnerships, if successful, can effectively manage the key aspects of regional affairs evenhandedly, and blunt Washington and Beijing’s need to directly oversee regional developments or compete for influence.

Nonetheless, establishing an enhanced basis for jointly handling regional affairs must overcome significant collective-action problems and major power opposition.

The enormity of such tasks places Singapore’s fate in the hands of potential collaborators and ad-hoc cooperation rather than the established institutions and regimes to which Singapore is accustomed.

Political dynamics in Asia may ultimately compel Singapore to re-examine its long-held position on external affairs. The old, comfortable approach of working with Washington for security and Beijing for prosperity — having its cake and eating it too — may be becoming increasingly unsustainable. Adjustments in US–China relations might turn Singapore’s fence-sitting from strategic advantage into cause for consternation.

Going forward, Singapore may have to be less complacent and more active in taking steps to handle the changing nature of Sino–US relations and its consequences for Asia as disentanglement becomes more difficult.

It may even need to demonstrate visible leadership on tricky issues ranging from managing disputes to regulating regional relations or tackling cross-border crime.

This means being prepared to take political risks.

Singapore and other actors can no longer simply hope for a happy middle ground between Washington and Beijing, and must instead address a much more uncertain and unpredictable reality. EAST ASIA FORUM

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ja Ian Chong is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the National University of Singapore.