What low-income countries need is not more economic growth, it’s less shrinking

It is widely accepted that countries are poor because their economies don’t manage to grow sufficiently. But, perhaps surprisingly, the ability to create growth is not what most poor countries are lacking. In fact, all countries actually have this ability. Instead, countries are poor because they shrink too often, not because they cannot grow.

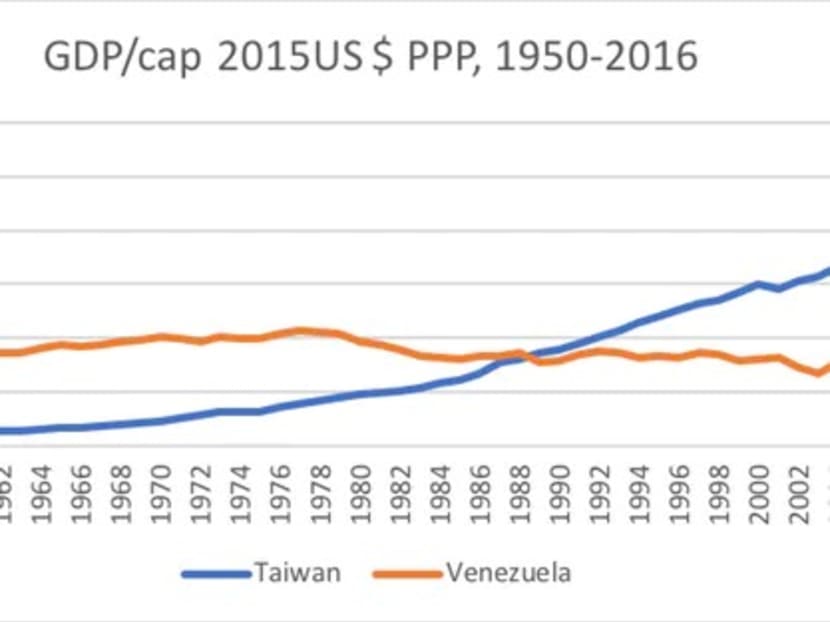

A metro running through Taipei. In 1950, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person in Taiwan was only about an eighth of Venezuela’s. By 2016, the tables had turned and the fortunes of both territories had been reversed.

It is widely accepted that countries are poor because their economies don’t manage to grow sufficiently. But, perhaps surprisingly, the ability to create growth is not what most poor countries are lacking. In fact, all countries actually have this ability.

Instead, countries are poor because they shrink too often, not because they cannot grow — and research by the United States National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that only a few have the capacity to reduce incidences of economic shrinking.

As the authors of this research say: “We show that improved long run economic performance has occurred primarily through a decline in the rate and frequency of shrinking, rather than through an increase in the rate of growing.”

Comparing development in Taiwan with that in Venezuela (see graph below) illustrates the point.

The X-axis shows years; the Y-axis shows GDP per person expressed in 2015 US$ Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). Source: The Total Economy Database from The Conference Board.

In 1950, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per person in Taiwan was only about an eighth of Venezuela’s.

By 2016, the tables had turned and the fortunes of both economies had been reversed. By then, the GDP per person in Venezuela was only a third of that in Taiwan.

This has very little to do with Venezuela’s inability to grow. With substantial natural resources, Venezuela can create growth and has done so. Indeed, the average per person growth rate during the years that the country’s economy did expand was 4.13 per cent — not an insignificant number.

Over the same period, Taiwan had a per person growth rate of 5.62 per cent during its own growth years. But this 1.5 per cent difference cannot explain the enormous difference in the two relative levels of prosperity in the two economies.

So, if the difference cannot be explained by growth, perhaps it can be by the frequency with which the two economies shrank. Tellingly, since the 1950s, the Taiwanese economy shrank only three times, while the Venezuelan economy shrank 31 times – almost every second year.

A GLOBAL ISSUE

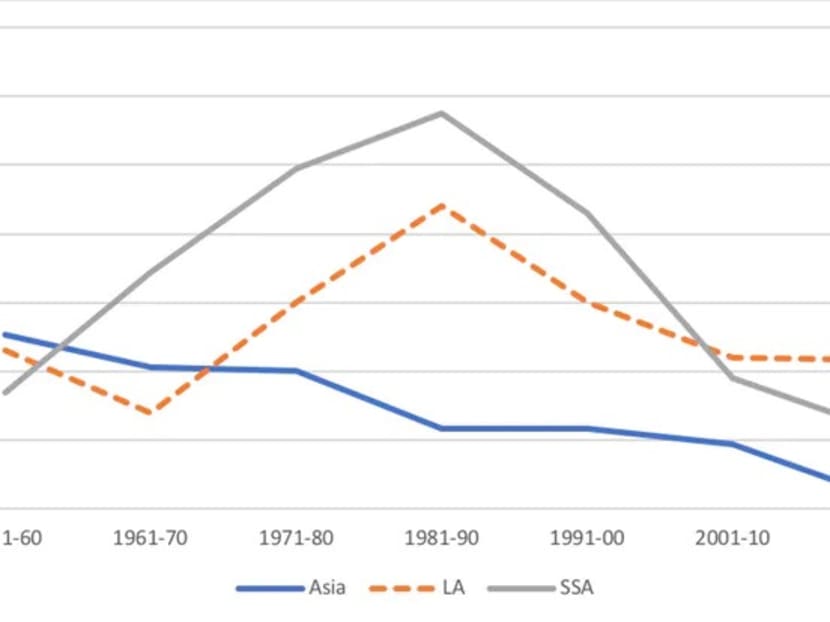

In the 1950s and 60s, many other low income countries in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia were experiencing shrinking of their economies with roughly the same frequency (see graph below).

The X-axis shows decades; the Y-axis shows the frequency of economic shrinking expressed as a percentage. The graph shows the average frequency of shrinking among the countries in each of the three regions per decade. The number of Asian countries = 17; Latin America (LA) = 10; Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries = 20.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, however, countries in Asia managed to reduce their incidences of shrinking while countries on the other two continents started to shrink more and more often. In the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, economies shrank, on average, every other year.

Again, in growth years, the Asian economies had an average annual growth rate per person that was only about 1-1.5 per cent higher than that during growth years in Latin America and Africa. But the Asian economies overall made much greater gains over the period.

Again, this shows that all countries can create growth but only a few can reduce the number of years they experience shrinking. These patterns are also in line with what new research in economic history is showing: That it is the ability to reduce economic shrinking that explains why the West grew rich and the rest of the world did not.

PEAKS AND TROUGHS

Ultimately, occasional peaks punctuated by frequent dips will not take you very far. Such a stop-go pattern will also waste resources, create uncertainty, deter investment and promote short rather than long-sightedness.

Studies on subjective well-being also show that people generally react much more strongly to economic loss than economic gain. This suggests that when the economy shrinks, when the absolute size of the cake diminishes, people respond more negatively than they do positively when things are on the up.

But in the ongoing discussion about global development and how to close the income gap between rich and poor countries, not least in the context of the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), there is no mention of how to limit the devastating impact of regular economic shrinking.

Despite this, we need to investigate more closely what social arrangements and institutions should be in place to limit incidences of economic shrinking.

The growth process very seldom is linear, especially in low income countries. Leading development economists have for some time complained that standard theories of economics might be relevant for understanding why economies grow, but are of little use for understanding why economies are different in terms of their ability to limit economic shrinking.

Theories of economic growth performance are geared towards explaining accumulation, allocation and perhaps innovation — but not shrinking.

WHAT TO DO?

We can still only speculate on what factors are important for creating resilience to shrinking and I am, together with a team of researchers, seeking to shed light on this puzzle.

It seems likely that countries with more diverse, sophisticated and “complex” economies are less volatile. Indeed, it appears essential that poor countries engage in manufacturing and new technologies.

Furthermore, inclusive societies with a more equal distribution of income, assets and economic opportunities are more likely to experience sustained growth.

Economies are probably also more stable and less prone to shrink if their governments are impartial, can stand free from the influence of vested interest groups, and deliver goods and services in a fair and efficient way.

Textbooks and policy agendas are filled with ideas about how to get growth going, but you’ll rarely read about what countries should do to avoid regular shrinking.

This leads to a flawed understanding of what low income countries should prioritise in order to create better standards of living, meet the SDGs, and catch up with rich countries.

We need to recognise that occasional high rates of economic growth, sometimes reported in the financial media as an annual contest between countries, are more a sign of volatile and unsustainable development than a measure of the prospects for long term development.

We also need to acknowledge that striving for a less shrink-prone growth process, rather than chasing short term high growth, is socially, economically and environmentally more sustainable.

We must learn from economies that have gone from frequent shrinkers to infrequent ones. If we know more about what those countries managed to accomplish, there are grounds for optimism in an economically less divided world.

Ultimately, however, we would be wise to pay greater attention to resilience to economic shrinking than continue our one-sided focus on economic growth. THE CONVERSATION

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Martin Andersson is Associate Professor, Lund University, who specialises in the process of economic development in low- and middle-income countries.