Gen Y Speaks: How I overcame hardship and self-doubt as a marine scientist, with some help from giant clams

As a young Asian female marine scientist, I have felt left out and isolated in many global academic-related meetings and discussions, especially those where I’m a minority in a predominantly male setting. It didn’t help that I was researching on a highly niche subject — the giant clam.

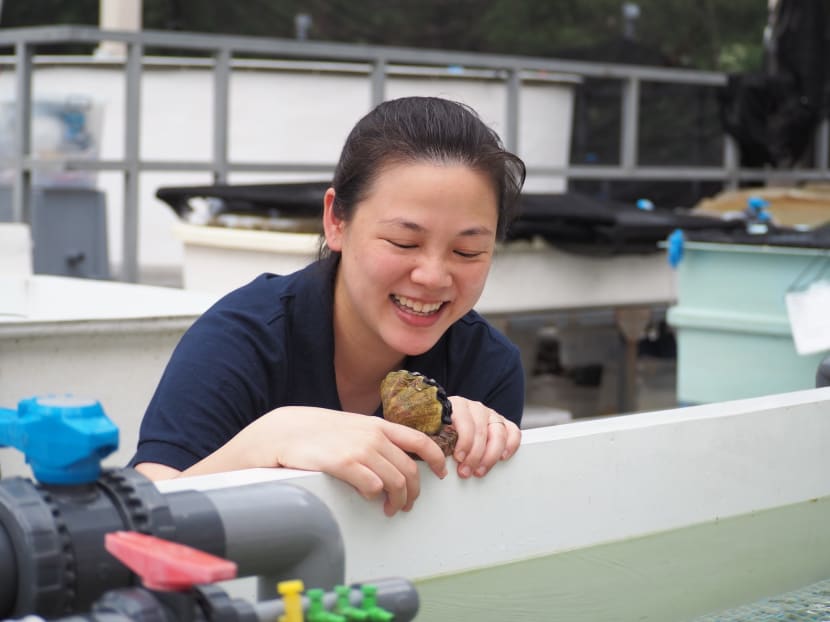

The author with a giant clam cushion at the Western Australia Museum. In her 15 years researching giant clams, she has experienced self-doubt which led to question her decisions to get a doctorate degree and pursue a career in science.

I was very fortunate to have spent most of my growing up years in the 1990s and 2000s exploring the outdoors on our sunny island.

I’ve always felt a certain affinity with nature, and was especially curious about the biodiversity that I encountered on these trips.

I’ve never had a favourite animal that I can recall. This all changed when I sought a research project as a second-year biological science undergraduate in 2006.

I remember checking the listings of projects online and finding only two options.

The first one was an investigation on the physiological responses in lungfish and the other was understanding the behavioural ecology in giant clams.

It was an easy pick for me as another personal criterion was to do something outside the lab.

When the time came to meet the giant clam face-to-face at the marine station at St John’s Island, I was amazed and amused to find it measuring all of 5cm.

For a clam with a big name, I was expecting the animal to be much larger than the size of my palm.

I was later corrected by my seniors who explained that these were baby giant clams grown in the marine station for experiments, and that these gentle giants could grow up to 1.5m long.

It was not love at first sight for me with the giant clam — it was an odd-looking creature that looked nothing like the clams I’ve seen in the supermarkets.

This first unexpected encounter with the giant clam initiated a chain reaction that led me to building my career as a marine scientist focusing on marine conservation issues.

Becoming a marine scientist was not part of my plans.

Instead, I was meant to go into teaching to fulfil my scholarship bond.

As I approached the end of my bachelor’s degree, my hard work won me the right to continue researching the giant clams for a two-year master’s degree.

By then, I was hooked on my research subject matter.

I reached a turning point of whether to continue pursuing a doctorate degree in marine ecology or fulfilling the teaching bond.

It was a time of much frustration and tears, and heavy conversations with my family who had to bear the brunt of financing the bond.

Eventually, they relented and loaned me money to break my teaching bond to pursue my passion for science.

Having overcome one hurdle, I continued to face challenges while trying to build a career as a woman scientist.

As a young Asian female, I have felt left out and isolated in many global academic-related meetings and discussions, especially those where I’m a minority in a predominantly male setting.

It didn’t help that I was researching a highly niche subject — the giant clam, and many of these meetings that I had attended usually focused on the charismatic organisms such as the corals and marine megafauna such as whales, sharks and sea turtles.

With very few peers to interact with and discuss my research work, I faced a lot of anxiety and self-doubt on the worthiness of my scientific research to the larger academic community, which led to underlying imposter syndrome issues.

I found myself questioning my earlier decisions on taking up a doctorate degree. Did I make the right decision for myself? Can I really carve out a career in science?

I also feel that the more hierarchical work environment in academia has led to unconscious biases and discrimination against women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Stem) fields.

It was difficult to see myself as a successful scientist as I did not have a female figure in Stem fields who “looks like me”.

There were moments when I felt like giving up on science.

So when I had received news that I was selected to be part of the renowned TED Fellows programme in 2017, I felt a tinge of hope that someone out there had thought that my research work mattered.

Just when things were looking up for me, I suffered a traumatic personal loss that same year with a miscarriage at 21 weeks.

By this point in my life, I didn’t know how to function mentally and physically. I needed help, badly.

Help came to me in the form of a personal development coach, whom I had met through the TED Fellows programme.

Under her guidance, I began to reflect deeply on the issues that bothered me and encouraged me to tackle each of them by taking baby steps.

After six coaching sessions, I felt a sense of liberation. I have freed my mind from my own chains of insecurities.

More importantly, I also began to welcome success by my own definition, such as finding contentment in receiving notes from supporters of my work and mentoring students who also joined a career in science.

Despite my personal awareness, overcoming my insecurities was not so straightforward. It was a work in progress that took me around four years to accept my successes at work.

There are still times when I slip back into self-doubt, but I have now learnt to be kinder to myself.

I often tell myself: It’s perfectly okay to have bad days to cry and be alone and let out these frustrations.

Being able to embrace my vulnerabilities makes me a stronger person to take on my work again.

I can relate my personal struggles to the giant clam.

As tiny, microscopic larvae, the giant clam spends most of its time navigating the tough ocean environment to grow and survive.

Amid their struggles, they reveal to me “tips” on how they cope with these changes to eventually succeed in becoming an adult.

It may sound absurd to many that I took life lessons from a clam, but it has been an anchor when things don’t go too well for me.

Despite the odds stacked against them, they have shown me what it means to not give up easily on life and be brave to face these challenges even when the going is tough.

On the scientific front, the giant clam has deepened my understanding of marine conservation.

I’ve worked on countless research projects on marine wildlife but one experience made me realise science alone cannot save the oceans.

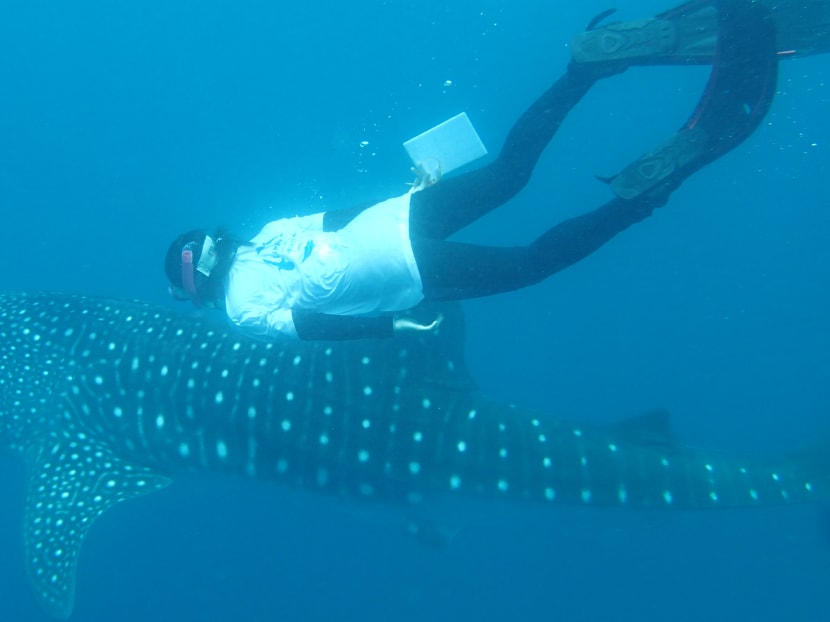

I took a research internship in the Philippines to observe the interactions between whale sharks and humans who lured them into lagoons daily for tourists.

I saw for myself that marine conservation is a complex web tangled with issues influenced by multiple stakeholders such as the whale sharks, fishermen, locals involved in tourism, tourists and scientists.

After this internship experience, I began to question and look for new ways to engage the masses on marine conservation.

I also began to work more closely on the ground to understand and navigate the complex conservation issues that surround marine wildlife in local coastal communities.

When I was starting out as a marine conservationist 15 years ago, there was no Greta Thunberg.

I applaud Greta’s determination in moving the needle for the youth-led climate movement, and showing young people around the world the endless possibilities for them to act now on climate change.

But the advocates I admire most are those already driving genuine local impacts in their homes and communities.

Many youths across the world, some of them young Singaporeans, through their own means, are leading conservation and sustainability projects ranging from protecting biodiversity to ensuring clean water supply to local villages.

They are my true inspirations.

As a parent now, I am responsible for the upbringing and well-being of my children, and this also means leaving them a planet where they can continue to live healthily.

I’m doing what I can for the environment today to ensure a future for my children tomorrow and I’m also heartened to know that there are a growing number of Singaporeans who are equally committed to conservation and protecting our oceans.

For all of the great things that have happened in my life, I am glad that I haven't given up. All thanks to a giant clam.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Neo Mei Lin is a senior research fellow at the Tropical Marine Science Institute, National University of Singapore. She is also the National Youth Council’s Singapore Youth Award recipient for 2019 and Asean Youth Fellow for 2021.