Gen Y Speaks: I chose not to study medicine because of my love for insects

Earlier this month, I started my first term at the University of Cambridge for a three-year degree in natural sciences. While many of my peers are entering medicine, I am pursuing my passion for biodiversity and entomology.

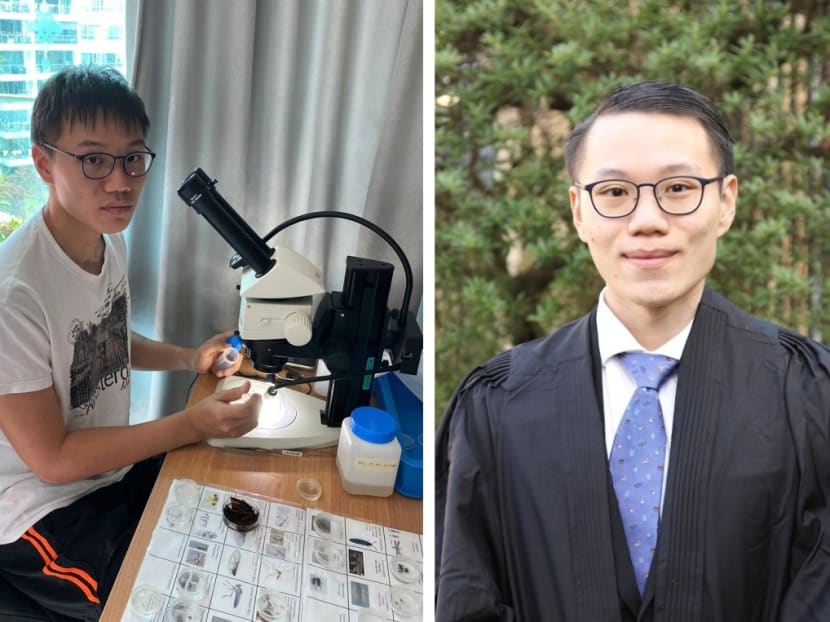

The author working at his makeshift home lab sorting insects during the circuit breaker period and at his matriculation at University of Cambridge.

Earlier this month, I started my first term at the University of Cambridge for a three-year degree in natural sciences. While many of my peers are entering medicine, I am pursuing my passion for biodiversity and entomology.

As a biology student, I was told by my parents to steer towards medicine for a “good job”. And while I did excel in biology, I never felt an inclination towards human biology.

Rather, I was more fascinated by the inner workings of insects.

It started when I was 17, on a visit to the Green Corridor for an extracurricular lesson on insect diversity.

Within my first half an hour of ever wielding a butterfly net, I found countless insects, each wildly different and specialised for their lifestyle and environment.

The sheer variety of insects made me want to discover more about this group of overlooked animals.

One that I specifically recall was a species of leafhopper. I had seen its sleek, red shell many times near my home, but this was the first time I was holding it on my palm.

My teacher described how it feeds on plant sap by piercing stems with its proboscis, and extracting nutrients, before forcefully shooting out excess water in a stream of droplets, thus giving them the common name of sharpshooters.

I was amazed by the unique behaviours and abilities of such a common insect, and wondered what other secrets I could learn from insects.

After that, I spent lots of time exploring green spaces to learn more about Singapore’s biodiversity.

I started by observing the flora and fauna in my surroundings, such as weaver ants near my home folding leaves into intricate nests, or the development of flowers near my class bench.

My friends thought I was a little obsessed, especially when I gave nicknames to the nearby snails, but they would always listen to my excited ramblings of today’s discoveries.

I participated in nature-related activities, which taught me about our natural world and introduced me to people who dedicated their lives to understanding and caring for biodiversity.

One person who greatly inspired me was Dr Ng Ngan Kee from the Department of Biological Sciences at the National University of Singapore, whom I met while in the International Biology Olympiad training team.

She taught us taxonomy, a topic I would not encounter in my own school curriculum.

She shared stories of her overseas adventures, spending entire days looking for new species of crabs, which was her area of expertise. She made no illusions to the fact that it was difficult, laborious work but it was also worthwhile and fulfilling.

Though my grades could qualify me for medical school, I was already tenuous on the prospects of studying medicine after hearing horror stories from my seniors of medical students leaving for work before sunrise and only going home late in the night.

Dr Ng’s stories made me realise that my interest could be more than a hobby and an actual career.

Under the recommendation of one of my junior college teachers, I applied for the natural sciences course at Cambridge and was delighted to be accepted.

The author checking camera traps — which are crucial for capturing data on native wildlife — at Mandai as part of his field work during his internship with Mandai Park Development. Photo courtesy of Daniel Lim Yu Hian

To gain more hands-on experience in biodiversity research, I contacted Dr Hwang Wei Song, an entomology curator at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

He recommended an internship with Mandai Park Development, which is funding the Mandai Insect Survey, an ongoing museum project to study the insect population in the secondary forests of the Mandai precinct.

My primary job in the survey was to collect insect samples from insect traps set up in the forested buffer areas of Mandai Rejuvenation Project, and to bring them back to the lab for sorting.

I would also help with data management, from cleaning up Excel sheets of wildlife observations to sorting through thousands of camera trap photos.

I learnt about the various field techniques used to gather insect samples and other biodiversity data, and the work that goes behind refining and processing this data.

Furthermore, I better understood the relationship between researchers and corporations, and the cooperation between them that allows research to happen.

During the circuit breaker, fieldwork had to cease. Although this was disappointing, there was a bright side.

I was allowed to bring home a microscope to continue sorting through insect samples. It felt very cool having my own mini lab at home, and it also meant that my parents could finally see the work I was doing.

At that point, my parents remained sceptical about my prospects in entomology and academia.

Afterall, it was an unconventional route that they, as IT professionals, were unfamiliar with. But seeing my mini lab and jars upon jars of insect samples piqued their curiosity.

They often asked to look through my microscope and queried why certain insects are classified in certain groups.

After coming into contact with my work, my parents understood that this was something of genuine interest to me. That it was not just a hobby gone too far, but also a legitimate, if unorthodox, career path to take.

Aside from working on the Mandai Insect Survey during his internship, the author also helped with other surveys, including a monitoring project for the Malayan colugo (flying lemur) in the Mandai area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Lim Yu Hian

Though my internship did not go as planned due to the circuit breaker, I still gained much from it.

It was difficult work, not just from the long hikes in the forests, but also from the hours spent gazing into a microscope to sort through what felt like a never-ending amount of insect specimens.

But in the end, I felt fulfilled and accomplished because the work contributes to scientific knowledge that hopefully helps to preserve and protect green spaces in Singapore.

Insects may live brief lives, but through the work of researchers, they become part of a scientific legacy that stretches far beyond human lifetimes. Being able to share this knowledge and love for these fascinating creatures makes this work meaningful to me.

I understand entomology is not for everyone. It is hard to appreciate insects when most of your encounters are chasing them out of your house.

But I hope that Singaporeans learn to better appreciate the vast world at our doorstep.

Each field is a hidden society; each pond a secret world, and each pile of leaves an ecosystem unseen. Singapore is not lacking in biodiversity, you only need to pay close attention to see it.

If you, too, have a passion and interest in a field that is less conventional, I hope you find the motivation and opportunity to follow it.

Find people who have the same interest; they might be more common than you think. There is no such thing as worthless knowledge. Much like how nature needs a diversity of organisms, the world can only progress with a diversity of people and ideas.

I chose to go to Cambridge not only due to the long history of biodiversity research in the United Kingdom, but also because I would be in contact with passionate and dedicated scientists from across the globe.

I hope to learn from the myriad of experiences of people who study vastly different organisms in wildly different cultures and environments.

I want to take this learning back to Singapore, and see how I can apply it to my own country.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Daniel Lim Yu Hian, 21, studied biology at Hwa Chong Institution and is now pursuing a three-year degree in Natural Sciences (Biology) at St Catharine’s College, University of Cambridge.