Seven things to know before leaping into the literary scene

SINGAPORE — The global success of authors such as JK Rowling, Haruki Murakami and Stephen King has cast a glamorous spotlight onto the world of literature, and many of us, I’m sure, are guilty of fantasising about spending carefree days at a cafe, writing a best-selling novel while sipping a cuppa.

SINGAPORE — The global success of authors such as JK Rowling, Haruki Murakami and Stephen King has cast a glamorous spotlight onto the world of literature, and many of us, I’m sure, are guilty of fantasising about spending carefree days at a cafe, writing a best-selling novel while sipping a cuppa.

Unfortunately, the business of publishing back home is not as rosy as it seems. Sure, there are some exceptional “unicorns” — we mean titles that have struck gold, and the hearts of readers — but plenty more have fallen by the wayside and made nary a ripple in the literary pool.

We share some little-known tidbits about the publishing scene, which we had gleaned during a backroom tour of Singapore publishers on Saturday (Nov 5), a programme organised as part of the 19th Singapore Writers Festival.

1) It is not a money-making venture

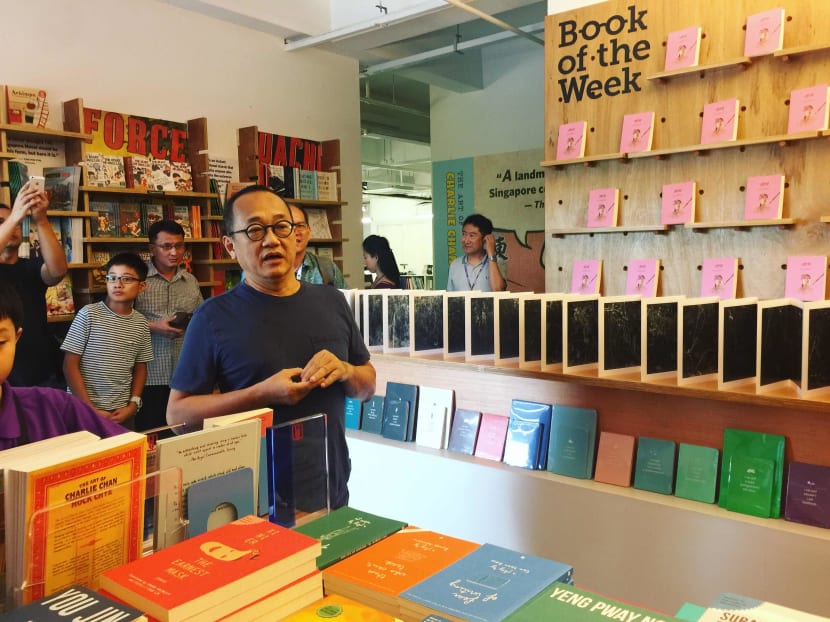

The publishers were unanimous on this front: Publishing does not make money, and margins, if any, are small. According to Edmund Wee, publisher and chief executive officer of Epigram Books, proceeds are usually split in this manner: “The bookshops take about 40 per cent, the distributor takes about 20 per cent, the author five to 10 per cent, and the publisher is left with about 30 per cent”. After paying the printer, the designer and rent, there’s only a margin of about five per cent, he said. “So if you sell (a book) in a bookshop for S$10, you are only getting S$0.50. You really need to sell big volumes in order to survive.” Founder of Ethos Books, Fong Hoe Fang, agreed, adding that the company has decided to “restrategise” and place greater focus on a smaller number of new books to keep costs down and ensure those that are printed get more attention. From next year, Ethos Books will be rolling out around 15 books a year, down from around 25, so it can focus more on marketing these books, he said.

2) Publishing is costly

Wee said Epigram spends about S$1 million to produce some 50 titles a year, and grants from the National Arts Council, while appreciated, only cover a small fraction of the cost. A grant ranges from S$2,000 to about S$4,000 on average per book, and the firm does not receive a grant for every book, he explained. In contrast, it costs S$20,000 on average to produce a book. “This year, we’ve got around S$56,000 so far from the National Arts Council for our publishing efforts. But we would have spent about a million dollars,” he added. This is also why since starting the company five years ago, it “still has not gotten into the black yet; we’re still in the red”.

3) In fact, publishing is more like a pet project, or a social mission

“Publishing in Singapore doesn’t make money at all, (but we are in it) because we believe in literature, we believe that reading will help to open up our horizons and allow us to have a peep into other people’s cultures,” said Fong. Wee said he went into book publishing — his company was a design firm initially — after looking “at the state of publishing in Singapore”. “I didn’t like the (local) stories, I felt there was too much navel gazing. I didn’t like the design of the book as well. To me it’s very important that when I buy a book, it must look good,” he said. He also had budding writers, graphic artists and photographers approach him, saying that they could not find a publisher for their work. “So we said, why not, although it’s financially more risky and we have all these problems,” Wee said. The design of the book became key, as did telling untold interesting stories. “I think we have a commitment to doing good things,” he mused.

4) Dreaming of selling millions of books? Unlikely.

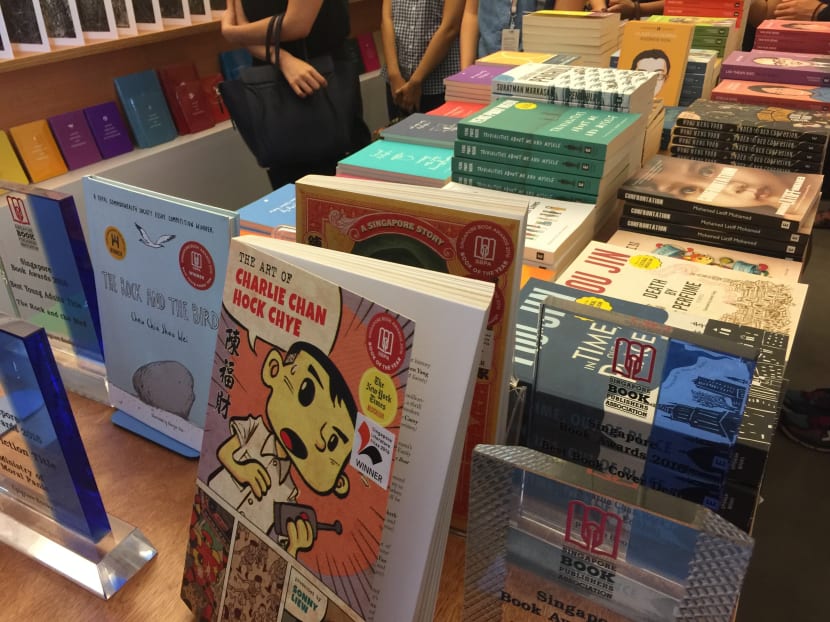

There are some hits, of course. Epigram’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye has sold about 14,000 copies so far, while the Amos Lee series has sold about 250,000 copies in total. The Sherlock Sam series has sold about 50,000 copies. Usually though, “if you can sell 1,000 copies, that is considered quite an achievement”, said Wee. “But 1,000 copies will never cover the cost of doing a book. You need to sell about 5,000 (to do that).” According to Ethos, a “good” title sells 4,000 to 5,000 copies — over a period of seven to eight years. However, a title typically sells less than 500 copies, it said.

5) Publishing just fiction alone is not enough

Rilla Melati Bahri, director of educational content producer Mini Monsters, says creating Malay-language story books for children alone won’t do. It has to “multi-task”, such as organising Malay enrichment programmes and speech and drama and workshops — its main trade, in fact — as well as conduct performances. “We realised that Singapore is such a small country, with the Malay population making up such a small number, so if you just depend on retail, you can sell Malay books until the day you die, you still cannot get the profit, because by sheer volume alone there’s just not enough buyers,” she pointed out, adding that the programmes keep them afloat. Similarly, Wee says Epigram still has to take on design jobs to supplement the expenditure. “Publishing doesn’t really make money so the design (portion) has to make a lot of money in order to support the publishing (end),” he said wryly. “It’s hard in Singapore. If you have a great book, you can sell 10,000 copies here. But the same great book can sell maybe 50,000 copies in the United Kingdom or United States, or maybe even 100,000 copies.” Fong added that Ethos, too, has to do commercial books, such as trade books for businesses. “That’s where our money comes from to help us fuel this passion,” he said.

6) You have to be great to get noticed

“If it is a subject that has been often written about, the quality of writing has to be really top-class,” said Ng Kah Gay, associate publisher of Ethos Books. For example, the firm is “flooded by a lot of manuscripts” on poetry that focus on the personal voice, so they would not stand out “unless the grasp of the language, such as the cadence, is very different”, said Ng, adding that Ethos receives an average of 50 manuscripts a year. “It helps if you have a great title,” suggested Wee. “Ninety per cent of the books we get, we change the title. Most of the titles (authors come up with) are too literary and not commercial enough.” For example, Now That It’s Over, by O Thiam Chin, which won the first Epigram Books Fiction Prize last year, was originally titled The Infinite Sea, while Wong Souk Yee’s Death of a Perm Sec was initially titled Expelled. Non-fiction genres also do better in Singapore, such as memoirs or self-help and inspirational books. “These books sell very well. Fiction — people feel that it’s a waste of time reading stories,” said Wee.

7) E-books are not king

Wee said while they are in the process of converting all their books into e-books, sales so far have not been encouraging. Epigram has put up 58 books on Apple’s iTunes, but “in one year, we only sold 18 copies”. Wee added: “It’s quite pathetic. Everyone talks about e-books, but actually once you put your books into Kindle and what not, there are five million books there. How are you ever going to find my book? It’s really very difficult, unless we have a big marketing campaign.”