Is Singapore’s hawker culture faltering?

SINGAPORE — Everybody in Singapore loves it. Renowned chefs such as Ferran Adria and Gordon Ramsay have raved about it. There is no doubt hawker grub is quintessential Singapore, and any Singaporean worth his or her salt would know where to tuck into the best char kway teow, chicken rice or laksa.

SINGAPORE — Everybody in Singapore loves it. Renowned chefs such as Ferran Adria and Gordon Ramsay have raved about it. There is no doubt hawker grub is quintessential Singapore, and any Singaporean worth his or her salt would know where to tuck into the best char kway teow, chicken rice or laksa.

But despite the renewed interest, the street food culture here is in danger of fading into the sunset. Why? Because older hawkers are retiring or passing away, and there is not enough new blood to take their place, said industry observers.

With the Government building 20 new hawker centres over the next 12 years — the first, co-located with Ci Yuan Community Club at Hougang Avenue 9, opened in August after a hiatus in 1985 — it is now more essential than ever to revitalise this tradition and attract a larger number of hawkers to run the stalls.

But, what is holding aspiring hawkers back from entering the trade?

While some may say entering the hawker business seems relatively simple with little capital cost, those in the know say it’s not as easy as it seems.

The biggest hindrance stems from a lack of opportunities for aspiring hawkers to learn how to cook and enter the business. There are no comprehensive and sustained efforts to ensure these continue for the long haul, said Makansutra founder KF Seetoh. “There is not enough information, not enough opportunities or support to ignite the continuation of this heritage food culture for tomorrow,” he noted.

Many younger hawkers also prefer to whip up what they feel is more interesting fare, such as fusion or western cuisine, and few know how to cook authentic dishes such as bak chor mee and char kway teow, he said.

And even if some aspiring hawkers do manage to learn some techniques, nobody teaches them how to market their food or which events to participate in, locally or regionally, to get more exposure, he added.

Seetoh had launched Street Food Pro 360 course last year to train the next generation of hawker entrepreneurs, but found it difficult to sustain. The subsidised programme was meant to give participants an overview of street food business operations, skills training and an understanding of the culture of Singapore’s food heritage.

“I felt the industry needed but ... Then I could not light it up,” he said. “I wish it was done on a larger scale, officially, at the higher level ... Ideally the Government should just take an old school and convert it into a street food academy,” he said.

Executive director of social enterprise Project Dignity Koh Seng Choon agreed. “Many people now want to have more experience before they jump in. They want to learn first,” he noted. “So you must have a structured learning process to train them, that’s what’s missing at the moment.”

While there are a few programmes out there (Fei Siong Food Management launched an entrepreneurship programme, for example); projects to train hawkers are relatively ad hoc and individual in nature, he said.

In 2013, a collaboration between Knight Frank, Business Times, YMCA, National Environment Agency (NEA) and Singapore Workforce Development Agency initiated the hawker master pilot training programme to train aspiring hawkers. It had “master hawkers” such as Thian Boon Hua of Boon Tong Kee Chicken Rice and Sulaiman Abu of D’Authentic Nasi Lemak impart their skills to trainees. While it was launched with much fanfare, the second round never took off in a big way because of a lack of sponsors. Due to the small budget, they are currently running the course for only four people, said Koh.

IT’S ABOUT SPACE AND PERCEPTION

Another problem, said industry players, is the lack of sufficient spots for aspiring hawkers to set up a stall. This was cast in the spotlight after Douglas Ng, 24, who runs a fishball noodle stall at Golden Mile Food Centre, complained about the selection process of upcoming hawker centre at Bukit Panjang. Ng said the shortlisting method adopted by NTUC Foodfare, which operates the hawker centre, was unfair and lacked transparency.

Foodfare clarified later that they had purposefully introduced a new set of criteria that would not award the stalls based on the highest rental bids. The new evaluation criteria is based on a scorecard with only 40 per cent weightage for tendered rent, while the remaining 60 per cent consists of quality, variety, selling price, operating hours, experience and concept. They had shared with interested tenderers during their briefing that only shortlisted cooked-food stall tenderers with the best scores were required to participate in a food-tasting exercise by a selection panel, said Foodfare.

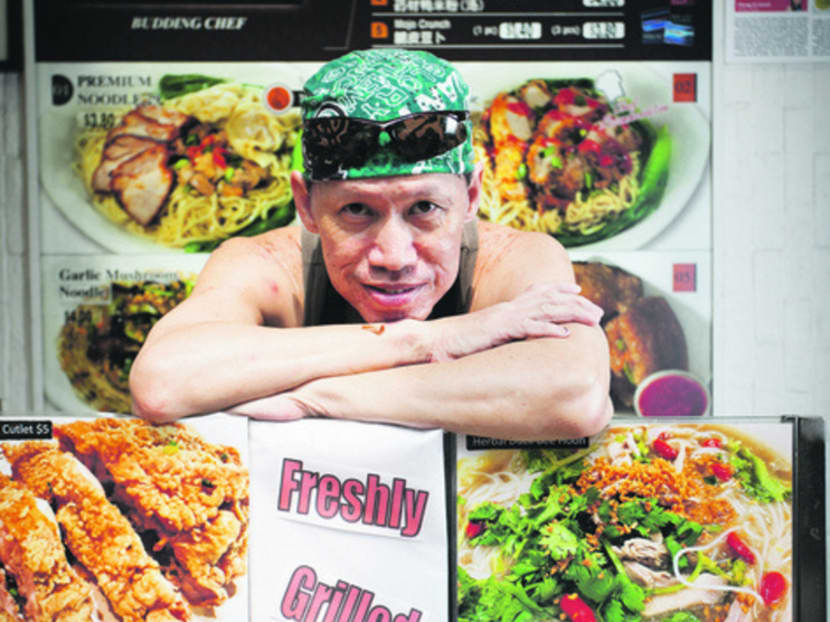

For new hawker Peter Mok, who opened his stall Noodle Evolution last December, finding an available location at Government-owned hawker centres was his biggest challenge. There are not many options — and not many stalls are available for bidding every month, with most meant for Indian or halal cooked food, he pointed out.

With few stalls available for bidding, Mok, a former quality assurance inspector in the apparel industry, had to bid for a stall at Kopitiam’s Lau Pa Sat instead, where rents are higher. Add maintenance and washing fees, and wages for workers; and it comes up to quite a large sum, he added.

Foodfare said the Bukit Panjang Hawker Centre had received more than 300 bids for six kiosks and 26 cooked-food stalls. An NEA spokesman also said that their cooked-food stalls “are generally well taken up”, with a vacancy rate of 2 per cent. NEA currently manages and regulates 107 markets and hawker centres.

But, observers say this is not reflective of interest from young hawkers. For instance, Seetoh pointed out that the number of bids also includes bids from existing players looking to expand their business. As for existing hawker centres, they are not vacant because many old hawkers refuse to let go of their stalls as they are paying old rental rates, he noted.

The stigma surrounding the hawker culture is another factor inhibiting the industry’s growth. Despite growing interest in hawker fare, fewer young people are interested because it is still seen as “unfashionable”, said Seetoh.

Hawker centres are seen as very hot and dirty, hawkers are not dressed well “and the presentation of food is not as fancy as many would like it to be”, he added.

“The bulk of a newer generation still likes to eat what’s trending online, such as pop-ups, food trucks, or artisanal farmer’s market type of food ... If given a choice, street food isn’t up on their list.”

This disconnect with hawker food among the younger generation also translates to their lack of enthusiasm in taking it up as a form of livelihood, he added.

While some young hawkers have emerged in the headlines recently - such as Ng, prawn noodle seller Li Rui Fang and Japanese teenager Reina Kuribara who is learning the ropes of serving mee pok from her father - this trend is “very sporadic and far and few between”, said Seetoh.

Many old hawkers also do not want their children to take over the reins, and so many types of “authentic food” may disappear, he said, citing Mitzi’s Cantonese Restaurant as an example. “With every falling legend, a chunk of heritage falls off.”

“The youngsters will not work in this kind of environment,” added Mok. “Nobody wants to work so hard because there are other opportunities available. (Old-style) hawkers are dinosaurs, society will evolve and they will no longer

be found. The hawker culture will change with the changing tastes of the newer generation.”

A SUBSTANTIAL SUM NEEDED

Then there are the financial risks of setting up a hawker stall. While these may be less daunting compared to a restaurant or cafe, it can still be considerable; and many face the problem of having enough seed money.

The prospect of having to bid for a stall and compete with more seasoned hawkers is another hurdle they’d have to face, said some observers.

Starting a stall at an old public hawker centre — including equipment, utilities and ingredients — could set a hawker back by some S$18,000 to S$20,000, said Seetoh. At private food courts, that could go up to S$50,000.

The challenge could be in having enough money to set up, as well as to sustain for at least three months, said Mok. “When you first start, your customer base is not established, so you may not be able to break-even, or make a profit, until three months later. You can have partners, borrow from banks, work in a stall and try to build up some cash, or borrow from relatives.

“This is one of the barriers to setting up — the basic finance,” Mok said.

Whether one can earn money from the business also depends on several factors, such as stall location, the number of operating hours, cost per bowl and the quality of the food.

“All these things have to be factored in before one opens a stall, but nobody teaches you that,” said Seetoh.

This is important as take-home profits for a hawker can range between S$2,000 to S$3,000 a month and a five-figure sum “for really good ones”, he noted; while Mok opined that hawkers can earn an average of between S$50 and S$1,000 a day.

NEA said several of their recent policy changes have lowered barriers of entry to the hawker trade. For example, the agency disallowed the practice of sub-letting or assignment of hawker stalls to prevent stallholders who have no intention of operating the stalls themselves from engaging in rent-seeking behaviour which could drive up food prices. It also removed the concept of reserve rent for tendered stalls in 2012, which resulted in some cooked-food stalls getting awarded for as low as S$1 rent per month.

“This has allowed aspiring hawkers to enter the hawker trade without having to pay high rentals,” said the spokesman.

NEA has also invited social enterprises to operate its new hawker centres, to bring new ideas as well as their experience in food and beverage operations, property and lease management, to diversify food options and enhance the dining experience, she added. “NEA will continue to explore suggestions and proposals from all stakeholders to ensure our hawker centre policies and initiatives remain relevant and continue to serve their social objectives.”

Still, a glaring loophole remains: Hawkers do not come under any ministry, neither does it have any central body that could guide hawkers, pointed out Victor Thya, the Singapore Marine Parade Merchants & Hawkers Association’s honourary secretary. Hawkers are usually members of loosely formed associations within their individual hawker centres, and the amount of help and guidance differs. A large part of their discussions are about logistics, such as which cleaning services to employ.

It would be nice if hawkers could have consultants provide advice and transfer skills, said Thya. “We just go our own right now — we survive on our own.”

Restaurants or small and medium-sized enterprises have associations of their own, hawkers do not, noted Koh. And while hawkers need to be licensed by NEA, they don’t require company registration. Without that and CPF contributions, it will be difficult to access Government grants, said Koh.

With an estimated more than 20,000 hawkers in Singapore, it is strange that this group is not taken care of, he added. “This is like a lost baby that nobody wants to look after. Hawkers have no parents.”

Added Seetoh: “NEA only runs hawker centres, they don’t own food culture. Nobody does. Perhaps the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth should.”