These women are the triple hot-shots in S'pore's photography scene

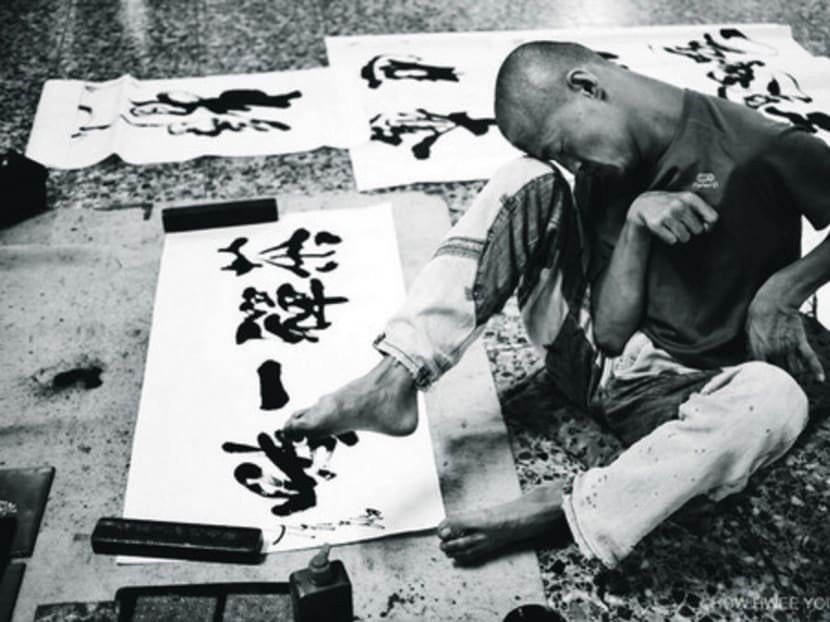

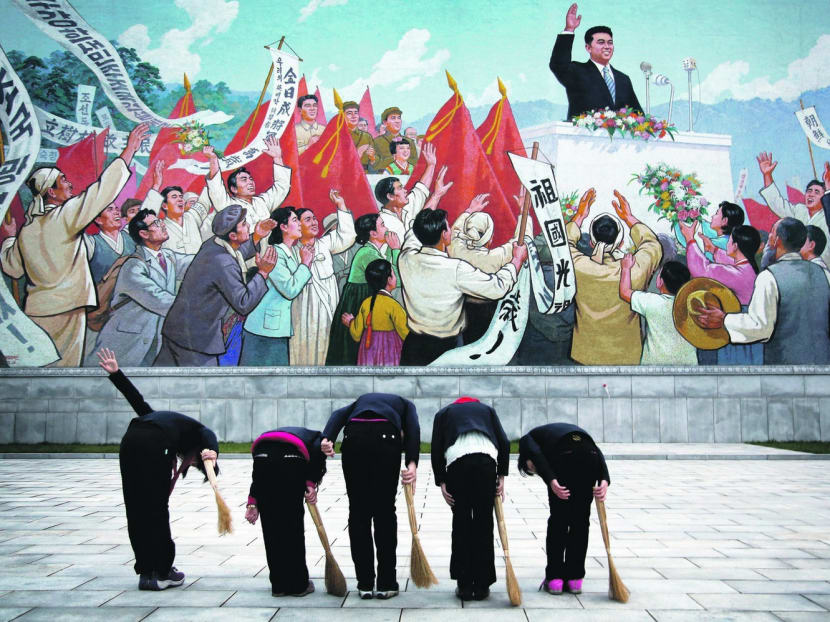

The man bowing before Lee Kuan Yew’s portrait; the Chinese miner with silicosis, piggy-backed by his wife; the street artist writing elegant calligraphy with his feet ... You might have seen these vivid, striking images in newsstands all over the world — in the pages of The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, Time and Foreign Affairs.

The man bowing before Lee Kuan Yew’s portrait; the Chinese miner with silicosis, piggy-backed by his wife; the street artist writing elegant calligraphy with his feet ... You might have seen these vivid, striking images in newsstands all over the world — in the pages of The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, Time and Foreign Affairs.

They are by, in fellow photographer Darren Soh’s words, “the three most successful Singaporean photojournalists/documentary photographers of our generation”, and it is time to open our eyes to their achievements.

The three photographers are all, coincidentally, women in their 30s, who cut their teeth in the local press. How Hwee Young went on to join the European Pressphoto Agency (EPA) in 2004. Covering Singapore and South-east Asia initially, she eventually joined EPA’s China bureau in 2010 and is currently chief photographer for the China region. Her work was exhibited in France in 2013 and she won a POYi (Pictures of the Year International) Award of Excellence in 2014.

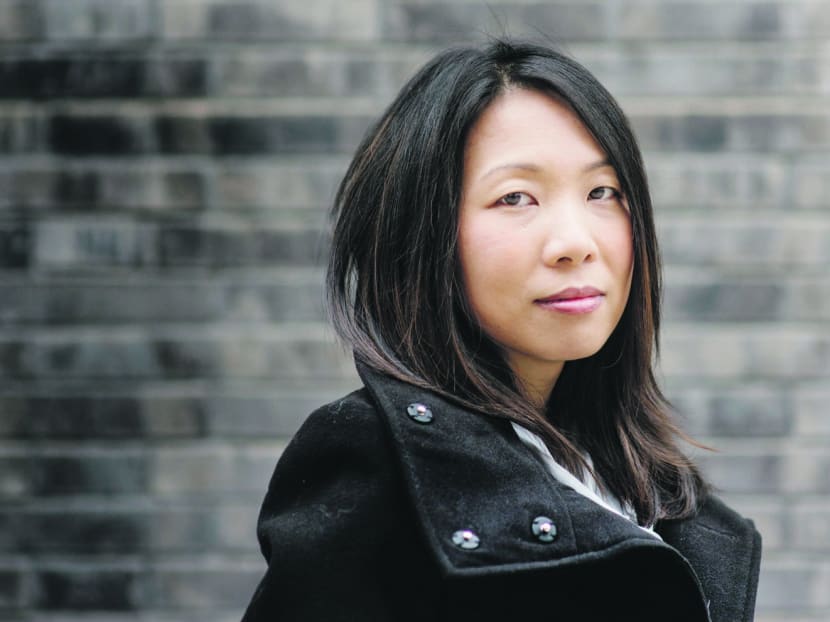

Wong Maye-E, 36, became an Associated Press (AP) photographer in 2003 and was named the AP lead photographer in North Korea in 2014. In September this year, her first solo exhibition opened at the Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film to an enthusiastic reception, seeing more than 4,500 visitors in the space of a month, according to the Objectifs director Emmeline Yong.

Sim Chi Yin, 38, began her career as a journalist for The Straits Times and became the China correspondent in 2007, before striking out on her own as a documentary photographer in 2010. This year, after two years of provisional membership, she became a full member of the prestigious VII Photo Agency. Her work has been exhibited in the United States, France, Norway and China, and she was identified as an emerging photographer to note by Photo District News in 2013 and by the British Journal of Photography in 2014.

Soh, 40, who had worked alongside the three photojournalists early in their careers, said: “Never have we had two successive representatives to the World Press Photo jury until them — Hwee Young (in 2015) and Chi Yin (in 2016).”

“I could not be prouder to have grown up with the three of them,” he said.

Tay Kay Chin, 51, another compatriot and well-known photographer, added: “Nothing happens by chance in this cut-throat world of photojournalism ... I am in awe of their works and know how hard they worked to be where they are today.”

STANDING OUT

The trio had also succeeded in a male-dominated field. How said she was the only female among the wire photographers based in Beijing (EPA, AP, AFP, Reuters, Kyodo and Getty Images), while Wong said that the number of male photographers she sees at big events, such as the Olympics, makes it “obvious that it is still a male-dominated profession”.

Sim summed it up: “There really aren’t many Asian women photographers practising in the international space, it’s still a pretty rare thing.”

Their success in this environment is as admirable as their humility and their down-to-earth, can-do attitude. All resisted being called pioneers and none felt especially disadvantaged by their gender or complained about having to compete in a male-dominated space.

“There are many other (female photojournalists) who have come before me and whom I very much look up to like former epa chief photographer and Pulitzer Prize winner Anja Niedringhaus who dedicated her life to covering conflict and its impact on people,” How pointed out.

Sim called gender a “double-edged sword”. She shared that in China, where she is based, she looks like a local young woman, which meant that she was “at the bottom of the food chain” and was sometimes “treated very badly”. For example, when she was on assignment with Western colleagues, she had been mistaken “for the interpreter’s assistant, or the maid”.

On the other hand, she also agreed with How, who said: “Being a female photojournalist also has its advantages, we are often seen as less intimidating than male colleagues and better able to gain the trust of our subjects and allowed better access in some situations.”

Wong said that being Asian has also helped her as a photojournalist, since she “doesn’t stand out in situations where (the presence of) foreigners is frowned upon”.

EMOTIONAL VS CEREBRAL

Gender aside, the three photographers have their own unique focus and styles. Sim’s best-known feature is Dying to Breathe, which documented the last four years of the late gold miner He Quangui’s life, and told the story of Chinese miners suffering from pneumoconiosis. Sim said that she prefers long-form storytelling, and it was clear that she was also passionate in her advocacy for disadvantaged social groups, from miners in China to migrant workers in Singapore.

Fellow photographer Bryan van der Beek, 40, describes her as “the consummate documentarian ... (She is) cerebral and really spends a lot of her time researching her subjects to give you a very fleshed out and well-rounded story”.

While Sim might come across as “cerebral”, Wong is, by her own reckoning, “emotionally driven”. “When I take a photograph, I usually feel something before I snap,” she said. She believes that “if you feel something in a moment — if you can translate that into your photograph — the viewer, somebody somewhere, can also feel that emotion from the photograph”.

Indeed, van der Beek says Wong is “visually astute, with a great ability to find the unique among the mundane, her photographs ... all have a story to tell, and she captures little snippets of life perfectly, which draws in viewers”.

Wong said she is grateful that her job allowed her to capture moments of “people coming together in times of disasters”. She hopes that her photographs could inspire others and enable them to salvage something positive from catastrophic events.

Like Wong, How has photographed disasters such as the Asian tsunami in 2004 and the Lushan earthquake in China in 2013, and major events such as the Olympics.

“However, the stories that touched me the most are the small, personal stories of remarkable individuals who have suffered life’s greatest adversities and survived to triumph over their problems,” she said, citing the stories of Xi Fu (a disabled street calligraphy artist) and Aishah Samad — a former national air-rifle shooter who had lost all four limbs to a severe bacterial infection but took up shooting again with robotic prosthetic limbs.

This unassuming trio are the eyes through which much of the world will see China, North Korea and South-east Asia. They are our standard-bearers even if they are too humble to say so themselves. They show us the heights to which we can, and should, aspire.

Sim Chi Yin’s Dying to Breathe: Portraits is currently showing at the Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film as part of the Women in Photography exhibition until Sunday.