The economic pragmatist

He was a man unafraid to challenge the popular ideologies of the day; he had no truck with dogma. Right up to the end of his life, Mr Lee Kuan Yew believed in constantly adapting to the hard realities of a changing world, and to refresh his “mental map”, he ceaselessly sought out the views of experts, academics, industry, political leaders, journalists and the man in the street.

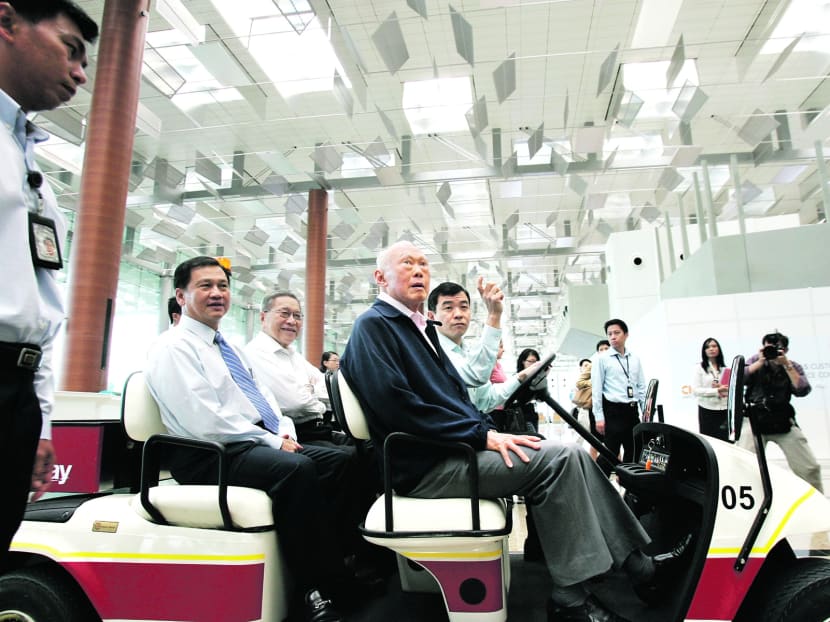

Mr Lee being led on a tour of Changi Airport’s Terminal 3 by CAAS director general and CEO Lim Kim Choon in 2007, when Mr Lee was Minister Mentor. TODAY FILE PHOTO

He was a man unafraid to challenge the popular ideologies of the day; he had no truck with dogma. Right up to the end of his life, Mr Lee Kuan Yew believed in constantly adapting to the hard realities of a changing world, and to refresh his “mental map”, he ceaselessly sought out the views of experts, academics, industry, political leaders, journalists and the man in the street.

But having listened to and processed their arguments, he did not let himself be swayed if he absolutely believed something was in the best long-term interest of Singapore. Changi Airport — and a large part of the Singapore economic miracle — stands today as a symbol of this.

When Singapore wanted to expand its airport operations in the early 1970s, a British aviation consultant proposed building a second runway at the existing airport in Paya Lebar as that would entail the lowest land acquisition costs and the least resettlements.

Although the Cabinet accepted the recommendation, Mr Lee asked for a reassessment by American consultants, and then a further study by a committee of senior officials on the viability of transforming the RAF airfield in Changi into a commercial airport. Both said to stay with the Paya Lebar plan.

But Mr Lee was unsure whether that would be wise or sustainable for Singapore in the long run, recalling lessons he had picked up on his travels: “I had flown over Boston’s Logan Airport and been impressed that the noise footprint of planes landing and taking off was over water. A second runway at Paya Lebar would take aircraft right over the heart of Singapore city ... we would be saddled with the noise pollution for many years.”

Reluctant to give up on his preference for the Changi site, he appointed the chairman of the Port of Singapore Authority, Mr Howe Yoon Chong — who had a “reputation as a bulldozer” — to chair a top-level committee for a final reappraisal. They reported that Changi was do-able.

And so, despite the fact the 1973 oil crisis had just struck and growth in South-east Asia was uncertain following South Vietnam’s fall to the communists, Mr Lee took the “S$1 billion gamble” in 1975 to build the new Changi Airport — demolishing buildings, exhuming thousands of graves, clearing swamps, reclaiming land from the sea and completed the building in six years instead of 10.

To say the least, that “gamble” has paid off handsomely, entrenching Singapore as a vital tourism, aviation and economic node.

THE ACID TEST: ‘WOULD IT WORK FOR US?’

How Mr Lee turned around the “improbable story” of Singapore abounds with examples like this, where he stuck to a hard-nosed, pragmatic approach coupled with a visionary outlook in implementing solutions he believed would make Singapore survive and last, even if it went against so-called conventional wisdom.

“In a developing country situation, you need a leader ... who not only understands the ordinary arguments for or against, but at the end of it says, ‘Look, will this work, given our circumstances? Never mind what the British, what the Australians, what the New Zealanders do. This is Singapore. Will it work in this situation?’” he said.

Mr Lee demonstrated time and again his ability to put on the lenses of a pure empiricist who could rise above prejudices and preconceptions.

Early on, he ditched the Fabian school of socialism — a style of governance he had been so enamoured with during his university days in Britain that he had subscribed to the society’s magazines for years after his return. He saw that its ideals would not work in reality. “We have to live with the world as it is, not as we wish it should be,” he once famously said.

In the early years, in defiance of the prevailing theory then that multi-national corporations were neo-colonialist exploiters who sucked developing nations dry of their cheap land, labour and raw materials, Mr Lee — acting on the advice of the Republic’s Dutch economic guru Albert Winsemius — actively courted foreign investors with a liberal economic policy which included attractive tax and fiscal incentives.

Dr Winsemius’ “practical lessons on how European and American companies operated” showed Mr Lee how “Singapore could plug into the global economic system of trade and investments by using their desire for profits”.

He explained the bold decision thus: “The question was, how to make a living? How to survive? This was not a theoretical problem in the economics of development. It was a matter of life and death for two million people.”

Looking back, Mr Lee believed that staying pragmatic ensured Singapore’s survival and success. “If there was one formula for our success, it was that we were constantly studying how to make things work, or how to make them work better ... What guided me were reason and reality. The acid test I applied to every theory or scheme was, would it work? This was the golden thread that ran through my years in office. If it did not work, or the results were poor, I did not waste more time and resources on it.”

LEAP OF FAITH

Living with reality did not mean resigning to fate or operating in ‘safe’ mode — on the contrary, Mr Lee was restless about innovating and turning adversity into opportunity. Many things could go wrong, he’d said, but: “The crucial thing is: Do not be afraid to innovate.”

Former civil service head Peter Ho said many of the big leaps forward in the early years of fledgling Singapore were “nothing more than acts of faith”.

“It is a myth that everything in Singapore is planned down to the nth degree, that nothing is expected to go wrong, and that the government operates in a fail-safe mode,” said Mr Ho.

“The first container port at Tanjong Pagar was a big risk, as the container was by no means a proven mode of transportation. But Lee Kuan Yew gave Mr Howe Yoon Chong, who was then Chairman of PSA, enough leeway to make the move to Tanjong Pagar.”

Indeed, Mr Ho added, “that willingness to try things out spawned a generation of state entrepreneurs who created, almost out of nothing, national icons like Singapore Airlines, DBS, ST Engineering, Changi Airport, Singtel, and so on. The national computerisation programme is another example, started in the Ministry of Defence, which transformed Singapore.”

Early on, Mr Lee and his team recognised the importance of science and technology to the economy (English was chosen as a medium for school education in part because it best conveyed such subjects).

CLIMBING ON OTHERS’ SHOULDERS

Mr Lee was also always looking for solutions for Singapore by drawing lessons from other countries’ experiences or seeking out experts. No need to reinvent the wheel, as he repeatedly said.

On his travels, he watched “how a society, an administration, is functioning. Why are they good?”. He took notes on matters as diverse as tree species or industries that might work for Singapore.

It was through this form of inquiry that, for instance, Mr Lee instituted various anti-pollution measures here. He started vehicle inspections after seeing cars lining up at garages to be certified up to mark when he was in Boston in 1970; and he sited factories away from residential areas because he saw Japan’s troubles with Minamata disease and pollution in the early 1970s.

“I preferred to climb on the shoulders of others who had gone before us,” he said.

And if the help of experts was needed in order for problems to be solved, Mr Lee would get them — no matter where they came from. For instance, when Singapore urgently needed to build up defence forces as a deterrence against potential blowback from Malay Ultras after Independence in 1965, and India and Egypt did not respond to requests for help to build up battalions and coastal forces, Mr Lee turned to the Israelis — in spite of possibly agitating Malay Muslims in Singapore and in Malaysia.

Nonetheless, when the first groups of Israelis, led by Colonel Jak Ellazari, came in November that year, they were called “Mexicans” to disguise their presence.

FINANCIAL SYSTEM REFORM

While Mr Lee stood by unpopular decisions that were for the long-term good, he also knew when to change course to maintain Singapore’s relevance or capture future opportunities.

For years, Mr Lee had believed in strict regulation of the financial system and in protecting the local banks. But then the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis broke.

Recalled Mr Heng Swee Keat, who was then Mr Lee’s Principal Private Secretary and who later served as Managing Director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS): “Our stringent rules, while appropriate in the past, were now stifling growth and our banks were falling behind. Mr Lee was persuaded that our regulatory stance had to change.”

Mr Lee, who was then Senior Minister, came up with a calibrated broad plan that he discussed with and sought PM Goh Chok Tong’s approval for. This led to a major review of policies and the transformation of MAS.

In a 1999 interview, Mr Lee pointed to the game-changer of e-banking and the Internet. “If this government carries on the way I did over the last 30 years, protecting local banks to make them grow, then it’s in for trouble. We are a venue for 200 of the world’s biggest and most competitive banks. Unless we get ourselves up to a comparable level, we’ll be like New Zealand, where all their own banks have been taken over and are foreign-owned.”

Said Mr Heng: “If Mr Lee had not initiated the changes in the late 1990s, and sought to turn adversity into opportunities, we would not have become a stronger financial centre today. To prepare ourselves to open up our financial system in the midst of one of the worst financial crisis is, to me, an act of great foresight and boldness. It has the stamp of Mr Lee.”

CASINOS, F1 AND GAYS

To be part of the 21st-century world — and the ruthless competition for talent, tourism dollars and investors — meant delicately recalibrating some issues of huge social sensitivity to Singaporeans.

In a 2007 interview, Mr Lee said Singapore took “an ambiguous position” on homosexuals — “we say, okay, leave them alone, but let’s leave the law as it is for the time being”. While places like China and Taiwan already had more liberal policies, he said: “But we have a part Muslim population, another part conservative older Chinese and Indians. So, let’s go slowly. It’s a pragmatic approach to maintain social cohesion.”

Mr Lee also reversed his earlier and long-held objections to holding Formula One races and allowing casinos in Singapore. He recognised that the F1 had a jet-set following and could generate economic spin-offs for Singaporeans. The larger goal of advancing Singapore’s position on the world stage also swayed Mr Lee, as he emphasised how the race allowed us to “telecast our unique skyline to billions around the world”. (The inaugural night race was held in 2008.)

On casinos — which he once said would be allowed only “over my dead body” — he explained in a New York Times interview in 2007: “I don’t like casinos, but the world has changed and if we don’t have an integrated resort like the ones in Las Vegas, we’ll lose. So, let’s go. Let’s try and still keep it safe and mafia-free and prostitution-free and money-laundering free. Can we do it? I’m not sure, but we’re going to give it a good try.”

He added: “We have to go in whatever directions world conditions dictate if we are to survive and to be part of this modern world. If we are not connected to this modern world, we are dead. We’ll go back to the fishing village we once were.”

More in our Special Edition this afternoon (March 23).