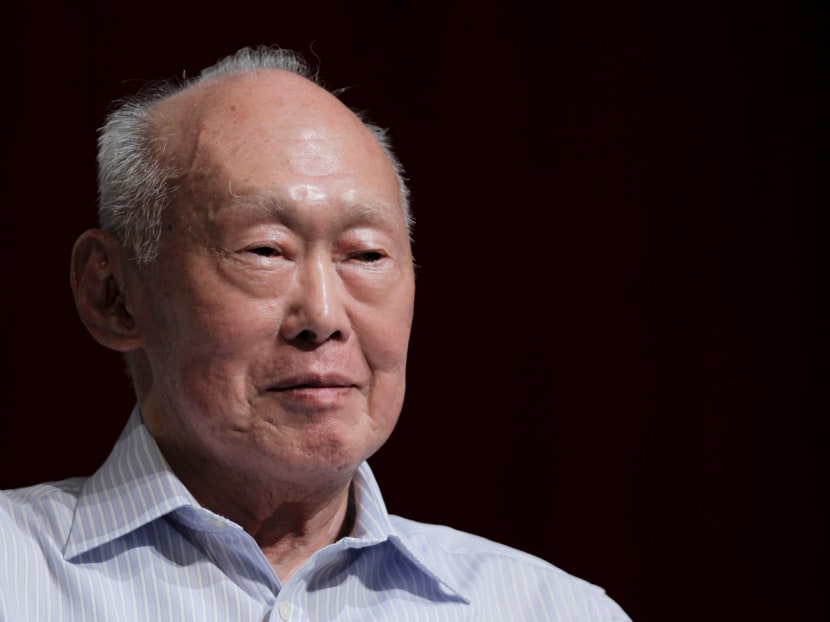

Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew dies aged 91

SINGAPORE — Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s visionary founding Prime Minister and architect of the country’s rise from a fledgling island nation expelled from Malaysia to one envied worldwide for its rapid economic progress, far-sighted political leadership and all-round efficiency, died today (March 23). He was 91.

SINGAPORE — Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s visionary founding Prime Minister and architect of the country’s rise from a fledgling island nation expelled from Malaysia to one envied worldwide for its rapid economic progress, far-sighted political leadership and all-round efficiency, died today (March 23). He was 91.

Mr Lee’s death came a few months shy of the 50th anniversary of the Republic’s independence on August 9.

In a brief statement announcing his death, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) said Mr Lee, whose health had been deteriorating over the past two years, died peacefully at the Singapore General Hospital at 3.18am this morning. “The Prime Minister is deeply grieved to announce the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore,” PMO said in statement issued just past 4am.

At about 6.20am, the Cabinet also issued a statement: “We will always remember his sound guidance, his constant questioning, and his fatherly care for Singapore and for all of us. Let us dedicate ourselves to Singapore and Singaporeans, in the way that Mr Lee showed us.”

Mr Khaw Boon Wan, chairman of the People’s Action Party - the ruling party which was founded by Mr Lee in 1954 - said in a statement that Mr Lee had devoted his whole life to Singapore. Mr Khaw said: “Millions of Singaporeans have improved their lives because of his dedication and sacrifice. As we mourn his passing, let’s also re-dedicate ourselves to building on his legacy, for the Party and for Singapore.

Mr Lee had been warded at SGH since Feb 5 after coming down with severe pneumonia. Despite a later statement that his condition had improved, he never recovered. His condition worsened progressively last week, statements from the PMO said, and a final update on his deterioration which arrived on Sunday afternoon said his condition had “weakened further”. At 4:05 am this morning, the announcement that Singapore had been bracing itself for and dreading for more than a month was made.

The Republic now enters a seven-day period of national mourning - from today to Sunday - for its founding leader, a man who inspired awe and was regarded as an intimidating presence at the start of his tenure as Prime Minister in 1959, but who later became synonymous with Singapore’s success and was widely viewed with respect and admiration — even if it was grudging in some quarters.

As a mark of respect to Mr Lee, State flags on all Government buildings will be flown at half-mast during the week of mourning.

A private family wake will be held today and tomorrow at Sri Temasek - the Prime Minister’s official residence on the Istana grounds. From today to Sunday, condolence books and cards will be placed at the Istana’s main gate for the public to pen their tributes to Mr Lee. Condolence books will also be opened at all overseas missions.

Mr Lee’s body will lie in state at Parliament House from Wednesday to Saturday, for the public to pay their respects. A State Funeral Service will be held at 2 pm on Sunday at the National University of Singapore’s University Cultural Centre.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest of Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s three children, addressed the nation this morning via live television.

Across a grieving nation, which had been bracing itself for bad news since it was announced a little more than a month ago that Mr Lee had been warded and subsequently put on a mechanical ventilator, grief gave way slowly to tributes for a man regarded as a modern-day titan, not just in Singapore, but in much of the world.

On the Internet, where his legacy was a more divisive subject than it was elsewhere, an unprecedented outpouring of condolence messages ensued, even though the news broke in the wee hours. Tributes from the public and political leaders began streaming in soon after PMO’s announcement.

Said Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong, who succeeded Mr Lee as Prime Minister in 1990, on Facebook: “My tears welled up as I received the sad news. Mr Lee Kuan Yew has completed his life’s journey. But it was a journey devoted to the making of Singapore.

“He has bequeathed a monumental legacy to Singaporeans - a safe, secure, harmonious and prosperous independent Singapore, our Homeland. He was a selfless leader. He shared his experience, knowledge, ideas and life with us. He was my leader, mentor, inspiration, the man I looked up to most. He made me a proud Singaporean. Now he is gone. I mourn but he lives on in my heart. On behalf of Marine Parade residents, I offer our profound condolences to PM Lee Hsien Loong and his family.”

President Tony Tan said: “Mary and I are deeply saddened by the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. We extend our deepest condolences to his children Mr Lee Hsien Loong, Ms Lee Wei Ling and Mr Lee Hsien Yang, and their families.”

In his three-page condolence letter to the Prime Minister, Dr Tan paid tribute to Mr Lee’s achievements, such as how he rallied Singaporeans together after forced separation from Malaysia in 1965. “Many doubted if Singapore could have survived as a nation but Mr Lee rallied our people together and led his cabinet colleagues to successfully build up our armed forces, develop our infrastructure and transform Singapore into a global metropolis,” Dr Tan wrote.

Condolences from world leaders also streamed in, with Australia Prime Minister Tony Abbott and New Zealand Prime Minister John Key among the first to pay tribute to Mr Lee.

United States President Barack Obama said he was deeply saddened to learn of Mr Lee’s death. Offering his condolences on behalf of the American people, Mr Obama described Mr Lee as a remarkable man and a “true giant of history who will be remembered for generations to come as the father of modern Singapore and as one the great strategists of Asian affairs”.

Mr Obama said his discussions with Mr Lee during his trip to Singapore in 2009 were “hugely important” in helping him to formulate US’ policy of rebalancing to the Asia Pacific. “(Mr Lee’s) views and insights on Asian dynamics and economic management were respected by many around the world, and no small number of this and past generations of world leaders have sought his advice on governance and development,” he added.

Obituaries also appeared on the websites of international media, including The New York Times, The Financial Times, The Economist, the BBC and the South China Morning Post.

The outpouring of grief reflected the stature of a man who led a team of able and equally visionary leaders and oversaw Singapore’s rise by formulating policies aimed at overcoming the myriad challenges faced by a tiny nation set amid what he described at the outset as a “volatile region”.

His ideas spanned the gamut, from Singapore’s place in the larger world, the defence of an island just 50km across, housing, education and economic policies, to the seemingly mundane, but which he explained were equally critical; these ranged from the orderly rows of trees seen across the island, for example, to the 1970s relegation of males with long hair to the back of queues to blunt the appeal of Western hippie subculture, which was deemed unhealthy for the country’s development.

At every turn along the way, and even after he stepped down from his last post in Cabinet following the May 2011 General Election, Mr Lee ceaselessly reminded Singaporeans of his prescription for the country’s success — or lit into its ills — with his signature blend of a politician’s oratory, a courtroom lawyer’s ability to wield a rapier to opposing arguments and a knack for persuasion. The merits of his arguments were always discussed, sometimes debated, but the astute observer always arrived at the same conclusion —that Mr Lee never stopped thinking about the challenges facing this country.

As he put it himself memorably: “Even from my sick bed, even if you are going to lower me into the grave and I feel something is going wrong, I will get up.”

His visionary leadership drew praise from all over the world, and the success of Singapore gave it a relevance and weight in global affairs that few small states ever achieve. Former US President Bill Clinton, for example, called him “one of the wisest, most knowledgeable, most effective leader in any part of the world for the last 50 years”.

Other world leaders were similarly effusive in their praise, and many, including heavyweights such as China’s Deng Xiaoping and Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, eagerly sought his views as they themselves sought to transform their countries.

To be sure, Mr Lee had his share of detractors. He went after what he deemed political “duds” with a vengeance, resorting sometimes to surprisingly sharp language: He once described how he carried a figurative hatchet in his bag, a weapon he would use against “troublemakers”. His use of lawsuits against political opponents and Western media outlets which were accused of meddling in Singapore politics drew much criticism, as did his iron grip on the local press — he insisted at the outset that there was no “Fourth Estate” role for it, and that its business was as a nation-building entity.

Mr Lee also waded into areas citizens deemed private, such as his ventures into social engineering via the Graduate Mothers’ Scheme or the Speak Mandarin And Not Dialects campaign, and drew flak as a result. Policies such as the banning of chewing gum, meanwhile, drew a mix of criticism and ridicule internationally.

He remained unapologetic, however, insisting that whatever he did was in the better interests of Singapore. He stood by his belief, which he explained starkly in an interview published by National Geographic magazine in 2010, that to be a leader, “one must understand human nature. I have always thought that humanity was animal-like. The Confucian theory was man could be improved, but I’m not sure he can be. He can be trained, he can be disciplined”.

It was a theme he touched on several times, including as early as 1987, when he shrugged off criticism of meddling thus: “I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn’t be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters – who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think.”

EARLY YEARS

Mr Lee Kuan Yew was born on Sept 16, 1923, the eldest child of Mr Lee Chin Koon and Madam Chua Jim Neo. The relatively prosperous family included three brothers, Dennis and Freddy Lee, Lee Suan Yew, and a sister, Monica.

A natural at school, he topped the standings for the national Senior Cambridge exams among students in British Malaya, which included Singapore, and went on to Raffles Institution, but World War II interrupted his progress. After the war, armed with sterling grades, he went to London and earned a law degree from Cambridge. The war years and his time in London stirred a political awakening in the young Mr Lee.

Upon his return in 1950, Mr Lee and his wife — the love of his life and the woman he once described as smarter than he, Madam Kwa Geok Choo — set up the law firm of Lee & Lee. His law career was short-lived, however, and after a few years, he turned his gaze towards politics.

A brief but necessary retelling of this period, shorn of much of the complexity of those times, saw him set up the People’s Action Party and lobby — successfully — for self-government from the British and enter into merger with Malaya. It was what he firmly believed was necessary for the survival of a tiny island with no natural resources to speak of.

The merger ultimately collapsed, undone by sharp differences in political and economic policies between the ruling parties on both sides, which boiled over into racial unrest between the Chinese and Malays.

On the morning of Aug 9, 1965, Singapore was expelled from the Federation. Hours later, at a press conference, a visibly emotional Mr Lee explained why he had believed — for the “whole of my adult life” — that merger was the right move, but that separation was now inevitable, and called for calm. It was during this press conference that the indelible image of him with tears in his eyes came to be. It was a powerful testament to the anguish that separation wrought in him.

For a nation suddenly cut adrift, uncertain of what the future would bring — or, indeed, if there was one — his vow that there would be a place for all in Singapore managed to bring a measure of solace, and some steel, to the occasion.

THE ARCHITECT OF MODERN SINGAPORE

From the beginning, he and his team set out to remake Singapore in every sense of the word. The larger details of how they set about to do it and the results they achieved have been the subject of effusive praise, academic tomes, and much more besides.

From rehousing a squatter population in Housing Board flats with modern amenities, to conjuring up the defence of Singapore from practically nothing, to formulating an economic policy that took a fledgling nation — to borrow the title of his book — From Third World to First, Mr Lee had a leading hand in all.

There were numerous other decisions he took that have been the subject of much less publicity, but which have had significant claim to the success Singap ore has enjoyed. The policy to adopt English as the lingua franca for Singapore, the approach to foreign policy, and even the decision to site the airport in Changi instead of redeveloping the old Paya Lebar site, are among them.

Essentially, as recounted in the book, Lee Kuan Yew: The Man And His Ideas, the prescription for the transformation of the nation boiled down to three elements: his view of the problem, his analysis of how it could be solved, and his assessment of Singapore society and what was needed for it to grow.

In an interview with American journalist Fareed Zakaria published in 1994, Mr Lee described the route he and his team took to remake Singapore. “We have focused on basics in Singapore. We used the family to push economic growth, factoring the ambitions of a person and his family into our planning. We have tried, for example, to improve the lot of children through education,” he said.

“The government can create a setting in which people can live happily and succeed and express themselves, but finally it is what people do with their lives that determines economic success or failure. Again, we were fortunate we had this cultural backdrop, the belief in thrift, hard work, filial piety and loyalty in the extended family, and, most of all, the respect for scholarship and learning.”

He added: “There is, of course, another reason for our success. We have been able to create economic growth because we facilitated certain changes while we moved from an agricultural society to an industrial society. We had the advantage of knowing what the end result should be by looking at the West and later, Japan. We knew where we were, and we knew where we had to go. We said to ourselves, ‘Let’s hasten, let’s see if we can get there faster’.”

As Singapore’s success rounded into view, Mr Lee was often praised for his farsightedness. Less well-known, but just as important, was his obsession with detail, which ranged from how buttons should work down to the state of cleanliness of the toilets at the airport.

His prescriptions for excellence across all areas rapidly filtered down to the citizenry and, together with what has come to be known as the Pioneer Generation, Mr Lee and his team delivered success to Singapore in such meteoric fashion that the term “miracle” has routinely been used to describe the transformation of the country — without a trace of hyperbole.

Even while he was leading this transformation, however, Mr Lee had his eye on the future, specifically, an orderly and smooth transfer of power; it was something he viewed as critical to Singapore’s future success, and which was practically unheard of in the region and much of the developing world.

His intentions were telegraphed early, and moves were put in place after the 1984 General Elections. Much discussion of a handover ensued, and by the time Mr Goh Chok Tong was sworn in as Singapore’s second Prime Minister on Nov 28, 1990, the momentous event was viewed as routine.

Mr Lee was then appointed Senior Minister in Mr Goh’s Cabinet, a role akin to that of sage, and one which afforded him the opportunity to give his thoughts and advice on the issues confronting Singapore, though, by his own admission, he was keen to let the second-generation leadership run things and make the key decisions.

His views were also sought on matters beyond Singapore. Many leaders around the world, as well as leading media commentators, considered him an oracle of sorts on geopolitics, one to be tapped for his wellspring of insights into global affairs.

Much of what he thought of the world was shaped by experience, and he was viewed, first and foremost, as a pragmatist whose firm ideas of what would work and what would not were uncoloured by theories. In an interview with American journalist Tom Plate, he said: “I am not great on philosophy and theories. I am interested in them, but my life is not guided by philosophy or theories. I get things done and leave others to extract the principles from my successful solutions. I do not work on a theory.

“Instead I ask: what will make this work? … So Plato, Aristotle, Socrates — I am not guided by them. I read them cursorily because I was not interested in philosophy as such. You may call me a ‘utilitarian’ or whatever. I am interested in what works.”

With the template for the transfer of power in Singapore set, the nation underwent a similar process on Aug 12, 2004, when Mr Lee Hsien Loong was sworn in as the country’s third Prime Minister. Mr Lee Kuan Yew was subsequently appointed Minister Mentor in his son’s Cabinet, while Mr Goh assumed the mantle of Senior Minister.

In his speech at the swearing-in ceremony of the younger Mr Lee, President S.R. Nathan neatly encapsulated the factors that led to Singapore’s success, while also tracing the arc of Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s influence on the island republic, its unlikely beginnings, and its future path.

“This is only the second political changeover in nearly 40 years of our independence. Just as Mr Lee Kuan Yew did, Mr Goh is stepping aside to make way for a younger man when the country is in good working order,” he said.

“Political self-renewal is essential if the leadership is to refresh and remake itself, stay relevant to the changing political, economic and social environment and connect with a younger generation. An orderly and planned self-renewal process is being built into our political system. This is unique to Singapore and has served us well. It is the best way to ensure that Singapore maintains a consistent course, and continues to progress and prosper with each generation.”

Mr Nathan added: “The political changeover also marks a generational change. Mr Lee Kuan Yew led the founding generation who fought for independence and made Singapore succeed. The second generation, under Mr Goh, had the less obvious but equally challenging task of building a nation and rallying the people, when times were getting better and life more comfortable. Mr Lee Hsien Loong now leads the post-independence generation, who have grown up amidst peace, comfort and growing prosperity. Mr Lee and his government must engage the young on external and domestic issues which affect their future, update policies to reflect the aspirations of a younger generation of Singaporeans and adapt their style to stay in tune with the times.”

“Singapore was never meant to be sovereign on its own. To survive, we had to be different, indeed exceptional. We progressed and thrived because we built strong institutions founded on sound values — integrity, meritocracy, equality of opportunities, compassion and mutual respect between Singaporeans of different ethnic, religious and social backgrounds. The government, judiciary, civil service, unions, schools and the media have promoted the interests of the common people. The public, private and people sectors have built a national consensus on what the challenges are and how we can overcome them. The people and government are united.”

He continued: “These are valuable strengths and intangible assets critical to Singapore’s long-term survival and continued success. We must do all we can to preserve them.”

As Minister Mentor, Mr Lee’s pre-occupation with Singapore’s well-being continued. When he spoke in public, it was usually to remind Singaporeans of what worked for the country, and why it was necessary to do so. At his last appearance at his Tanjong Pagar ward’s National Day dinner on Aug 16, 2013, for example, he offered his views on one of his pet topics —bilingualism.

Speaking before a crowd clearly enthralled that he had turned up despite feeling unwell, he said: “Education is the most important factor for our next generation’s success. In Singapore, our bilingualism policy makes learning difficult unless you start learning both languages, English and the mother tongue, from an early age — the earlier the better.”

During his years as Minister Mentor, actors on the global stage continued to seek his views; he was a frequent guest on forums that included worldwide business leaders and appeared every now and then in the pages of leading publications.

As a measure of the stature he continued to enjoy, the high-powered board of French oil giant, Total, held its meeting in Singapore, instead of Paris, for the first time. During the meeting, Mr Lee announced that he, after 19 years on the board, intended to step down. Total chairman Christophe de Margerie would have none of it, however, and declared: “I refuse his dismissal, your resignation. If you don’t mind, you will stay as a member of our advisory board, which means you can come whenever you wish. It will be always our pleasure.”

Despite his advancing age and differing role in government, one thing did not change: His commitment to Singapore and his determination to see to it that everything, no matter how trivial it seemed, worked the way it should.

The keen observer would have spotted him in the unlikeliest of places. Here, being regaled by Formula 1 boss Bernie Ecclestone as the travelling motor circus staged its first night race beneath the twinkling lights of Marina Bay. There, riding a golf cart through the soon-to-be-opened Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resort and being briefed on its attractions and workings.

He also continued to worry about the way younger Singaporeans would view the challenges facing the country, and tried to drive the lessons he had learnt to them through his books.

The watershed general election of May 2011, beyond being historic in sending more opposition politicians to Parliament than ever before with the first loss of a Group Representation Constituency (GRC), also led to the end of Mr Lee’s decades in the Singapore Cabinet.

On May 14 that year, barely a week after the elections, Mr Lee and Mr Goh jointly resigned from Cabinet, and explained in a letter that they felt “the time has come for a younger generation to carry Singapore forward in a more difficult and complex situation”.

The letter added: “After a watershed general election, we have decided to leave the Cabinet and have a completely younger team of ministers to connect to and engage with this young generation.”

Mr Lee continued to remain in politics after this; he held on to his office as Member of Parliament for Tanjong Pagar GRC, but while he remained active behind the scenes, recurring bouts of ill-health took their toll, and he gradually receded from view, if not in influence, and made fewer and fewer appearances in public.

On Feb 5 this year, he was warded in hospital with severe pneumonia, but it was only two weeks later, on Feb 21, that Singaporeans learnt of the severity of his illness, when a statement from the Prime Minister’s Office announced that he was in the Intensive Care Unit of the Singapore General Hospital and was on mechanical ventilation. Despite a later statement that his condition had improved, he never recovered.

Mr Lee leaves behind his sons Hsien Loong and Hsien Yang, and a daughter, Wei Ling, as well as seven grandchildren.