The Big Read: Big data making a great difference in healthcare

SINGAPORE — It is a recurrent challenge of public hospitals here: Waiting times for patients at the emergency department. To tackle the issue at Changi General Hospital (CGH), Dr Chow Wai Leng and her team waded into three years’ worth of data: Who were the patients coming to the department and what were their numbers? On which days of the week and at what times of the day were they coming in? Were they acute cases?

SINGAPORE — It is a recurrent challenge of public hospitals here: Waiting times for patients at the emergency department. To tackle the issue at Changi General Hospital (CGH), Dr Chow Wai Leng and her team waded into three years’ worth of data: Who were the patients coming to the department and what were their numbers? On which days of the week and at what times of the day were they coming in? Were they acute cases?

After analysing usage patterns, the team proposed a redistribution of manpower to better match arrival patterns of patients. From July 2013, the emergency department rejigged its roster for doctors, arranging for greater overlap in their shifts during the peak hours of around 10am and 7pm to 8pm. The results soon followed, with average median time to first consultation for patients with more serious conditions shortened from 33 to 25 minutes, a 24 per cent improvement. Doctors have also reported a qualitative improvement in their workload, said Dr Chow, head of health services research at Eastern Health Alliance, which runs CGH.

The use of big data to derive insights for better decision-making — or analytics, which is fast becoming the new buzzword in both government and commerce — is slowly but surely changing healthcare here. Examples abound of how the crunching and analysis of data have improved hospital operations in recent years, and experts say greater things are in store, with analytics possibly having a greater impact on the clinical side of healthcare in years to come.

With more available data, software and human expertise, the hospitals have been able to take on problems ranging from the simple to the increasingly complex. They have been able to analyse workloads at various departments and clinics, categorise patients by medical history and their outcomes, and identify the best groups to target for various programmes.

At Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH), several staff were tasked to do scenario planning when its emergency department was quickly overwhelmed soon after opening in 2010. The hospital took the numbers crunched to discussions with the Singapore Civil Defence Force, arriving at the best geographical boundaries within which to accept ambulance-borne patients.

This was before KTPH’s Health Analytics Unit was formed. “We’d like to think that even before the arm was formed, we’d had a taste of how numbers could help us to make decisions,” said a KTPH spokesperson.

In another instance, the analytics team saved the hospital “quite a lot of money” that would have been spent on expanding the pneumatic tube system, which is used to transfer items such as blood samples and medication. They identified the root cause as users simply not sending items through optimal routes.

Changi General Hospital dived into data of thousands of diabetic patients under its Health Management Unit tele-health programme, and found that it was patients with poorly controlled diabetes who benefitted most from the periodic phone calls from nurses. This enabled the hospital to revise the enrolment criteria and deploy resources more cost-effectively.

JUST THE START

Analytics is set to make a bigger impact in the near future, say experts. Mr Benedict Tan, group chief information officer for SingHealth, said: “Right now, we’re doing a more operational kind of analytics, basically to fine-tune, improve efficiency and, to a certain extent, effectiveness. I’m more keen on the next two jumps to predictive analytics and preventive (care).”

Several healthcare clusters have begun to apply analytics to clinical projects. KTPH, for instance, is proud of a study which found that a questionnaire used for screening obstructive sleep apnea, a sleep disorder in which breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, could be used in the planning of critical care admission after surgeries. This is because people with a history of the disorder are under much greater risk when they undergo surgery, especially under anaesthesia, said a KTPH spokesperson.

Its healthcare analytics and anesthesia departments sought to localise the risk-scoring from the questionnaire, called STOP-BANG, to the local context. They administered STOP-BANG to 5,432 patients who had elective surgery in 2011, of whom 338 were admitted after surgery to critical care. Since the study was conducted about four years ago, the screening tool has been used on all KTPH patients undergoing surgery, for operative risk stratification and prediction of intensive care admissions.

At institutions run by SingHealth, which include KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, the National Heart Centre Singapore and Singapore General Hospital, a project called TrustedCare is being gradually rolled out for procedures such as elective Caesarean births, coronary artery bypass grafting and total knee replacement surgery. Each TrustedCare programme consists of indicators that will help collect data to track each patient’s care journey, with the objective of optimising and reducing variability in outcomes.

Indicators for coronary artery bypass grafting, for instance, include when the patient was given rehabilitation, whether blood transfusion was given in intensive care, and whether antibiotics were stopped within 48 hours after the operation. The institutions will be able to analyse data collected and review protocols to improve experiences for patients, said Mr Tan.

Experts have pinpointed distinct differences between big data analytics and research using traditional statistical methods. While the objective of the latter is inference and hypothesis-testing, the objective of big data analytics is data exploration, prediction and generalisation.

Big data in healthcare refers to electronic health data sets that are so large and complex that they are difficult to manage with traditional software or hardware, or traditional data management tools. This was according to academics Wullianallur Raghupathi of Fordham University in the United States and Viju Raghupathi of Brooklyn College at the City University of New York in an article published last February on the promise and potential of big data analytics in healthcare.

Analysts here told TODAY that data analytics have taken off thanks to greater availability of data and electronic health records, increasingly sophisticated software and more people trained to handle big data sets.

“Originally, people who analysed data in the healthcare sector were research scientists or people trained in epidemiology. They were more trained in managing smaller data sets,” said Ms Tan Woan Shin, principal research analyst at the National Healthcare Group’s (NHG) Health Services and Outcomes Research department. “Increasingly people who are trained in other disciplines like data mining techniques and computer science are coming into this domain. At the same time, we are also upgrading our skills to manage larger volumes of data.”

The National University of Singapore set up its Centre for Health Informatics in 2012 to train healthcare and IT professionals and offer two Professional Certificate in Health Informatics programmes. Over at NUS’ Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, health informatics is not yet part of the Masters in Public Health programme, said Associate Professor Teo Yik Ying, the school’s vice dean for research. But its biostatistics team is working on projects such as developing methods to mine huge data sets for complex diseases in humans, especially the genetics and genomics of infectious diseases.

LARGER SCALE PROJECTS UNDER WAY

Bigger projects, especially in population health, are underway at the regional healthcare clusters and on the national level, albeit at a nascent stage.

Alexandra Health System, which runs KTPH, aims to uncover the state of the population’s health in the north through health screenings, for predictive and planning purposes. It aims to screen 5,500 people a year.

“At this stage, we are gathering data,” said Mr Bastari Irwan, director of Alexandra Health Systems’ population health programme. “The idea is that with the data gathered, we can build a predictive model. We’ll know in X number of years how many (people with diabetes) will develop complications leading to blindness, kidney failure and limb amputation. So, what will be the landscape of healthcare demand for scenario planning, assuming we cannot change their course? That’s the kind of thing we are going to do further down (the road).”

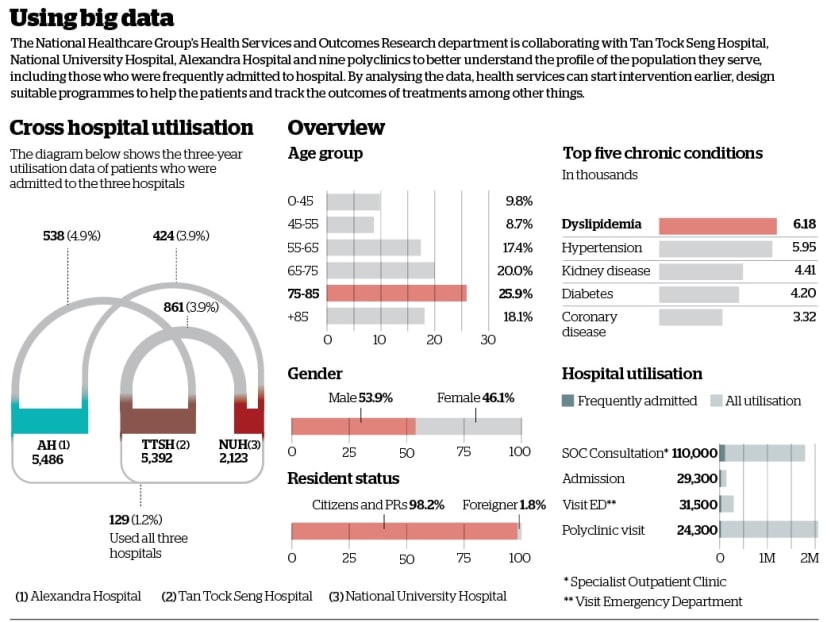

NHG’s Health Services and Outcomes Research department is collaborating with Tan Tock Seng Hospital, National University Hospital, Alexandra Hospital and nine polyclinics to better understand the profile of the population they serve — their state of health, the at-risk groups, ‘frequent admitters’ to hospital (people who have had three or more emergency inpatient admissions in a year), the diseases they have and services used, among other information.

“If we integrate primary care data (of the polyclinics), intervention may be able to start earlier,” explained Ms Tan. “By knowing the baseline, we can design suitable programmes. Analytics doesn’t stop there. We hope to use the merging of data to include outcomes that we are going to track for the population. Right now, it’s still very much in the works.”

In a speech last year at a healthcare analytics conference, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong said a robust and secure platform could be set up to accelerate analytical initiatives. The platform would link up data sources from public healthcare institutions, providers and other organisations, and even allow individuals to contribute data from self-monitoring devices. Mr Gan said the Health Ministry would start pilot projects this year to “test the concept and gain experience in this area”.

Big data and analytics have enabled the authorities to gain insights necessary to deliver care that is appropriate for the patient and the healthcare ecosystem, he said. “This is imperative in optimising our scarce healthcare resources.”

The Integrated Health Information Systems or IHiS, the Health Ministry’s IT arm, is helping drive analytics through powerful data warehousing systems and easy-to-use analysis tools that allow staff to more quickly analyse and transform data into information they can act on. The institutions are increasingly using automated dashboards to enable staff to view data in real time for swift and proactive decision-making, said Dr Chong Yoke Sin, chief executive of IHiS.

Analytics will enable Singapore healthcare to progress from treatment care to proactive healthcare for each patient, said Dr Chong. Proactive care refers to care provided on a pre-emptive basis, such as a regime to prevent potential diseases, re-admissions, and complications. Treatment care, on the other hand, is part of the care protocol for a particular episode of a disease or treatment.

The analysts said it is the potential to make an impact on a large number of people that drives them. “I still like to see patients but I feel that at a systems level, if you wanted to improve the quality of care, then the data-driven approach would probably reach out to more people,” said Dr Chow, a medical doctor by training.

Ms Tan is an economist by training and the daughter of a traditional Chinese medicine shop owner. Growing up, she watched customers return to thank her father for advice that helped them recover from illnesses. “I definitely can’t be a clinician because I’m scared of blood. But I can run an analysis,” she said. “The healthcare sector in Singapore is undergoing such big change, so it’s nice to be able to use some of the things I’m trained in and am good at to impact people, especially when they are sick.”