The Big Read: 17 years on, S’pore puts Sars lessons to the test in fight against Wuhan coronavirus

SINGAPORE — Like many others on the frontline during the Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome) pandemic in 2003, the resources of a family clinic in Chua Chu Kang had been stretched thin.

SINGAPORE — Like many others on the frontline during the Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome) pandemic in 2003, the resources of a family clinic in Chua Chu Kang had been stretched thin.

Personal protective equipment — N95 respirators, sterile gloves and full-body gowns — was scarce at a time when the world had never seen a virus like it, and people everywhere were desperately scrambling to stockpile emergency supplies for themselves.

Speaking to TODAY, Dr Tan Tze Lee, a general practitioner at the Edinburgh Clinic, recalled the difficulties that frontline healthcare workers faced when procuring equipment to protect themselves from the killer virus.

By the time Sars was contained in May 2003, it had infected 238 people and killed 33 in Singapore. Two in five of those infected had been healthcare workers.

While Dr Tan’s clinic thankfully encountered no cases, it remained on high alert for Sars patients in the four months of the epidemic in Singapore, throughout which the medical staff had to don full protective gear. But everyone was not ready for the crisis, said Dr Tan, who is also president of the College of Family Physicians Singapore.

Many continued to work but were extremely concerned that they might bring the virus home and put their loved ones at risk, he added.

“The healthcare practitioners in Singapore were ill-prepared, which resulted in sombre outcomes. Since then, we have learnt our lesson and measures were instituted to prepare us for any future pandemic event.”

“Here we are today, ready to fight the 2019-nCoV,” he said.

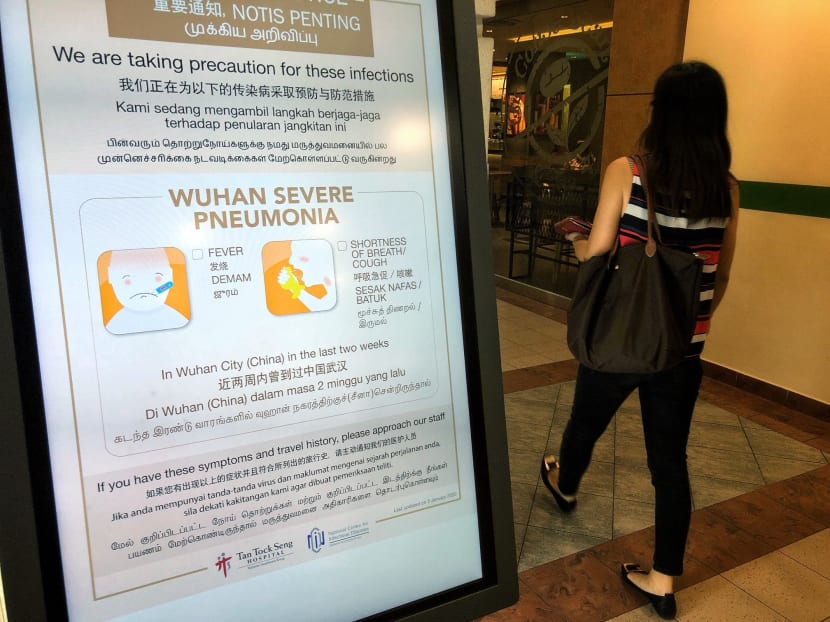

The current outbreak of the Wuhan coronavirus — or 2019-nCoV, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) temporary name for the virus — was first confirmed in Singapore on Jan 23. To date, all cases were imported, including a Singaporean who was in Wuhan, and there has been no evidence of community spread in the Republic.

The WHO has yet to declare the virus — which has spread to several countries — as a pandemic. Nevertheless, it was declared a global health emergency on Friday (Jan 31).

The first cases were reported in Wuhan in China’s Hubei province and believed to be linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which sells live animals.

As of noon on Friday, there were 16 confirmed cases with the virus here, 35 cases were still waiting for their test results and 198 had already tested negative. There are no deaths in Singapore thus far.

At the heart of the city-state’s response plan is the Disease Outbreak Response System (Dors), a crisis management plan which did not exist in 2003, but was drafted after Sars and refined again in the wake of the swine flu (or H1N1) pandemic in 2009.

“After Sars, we made a thorough review of the facilities we had – the infrastructure, hospitals, isolation wards, and the scientific testing and capabilities,” said Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, last week.

“I think we are much better prepared now.”

Currently, Singapore is at Dors condition (Dorscon) Yellow, signifying that the virus is severe and can infect from person to person, but is chiefly occurring outside Singapore. The next step up is Dorscon Orange,

which would have applied in the case of Sars, whereby the virus is spreading in Singapore but not widely, and is being contained.

While the plans are in place and some measures have kicked in, Singapore’s national strategy is still largely untested — since the Wuhan coronavirus is believed to be in its early stages in the Republic, medical experts and Sars veterans told TODAY.

However, there are ample signs that the lessons from Sars are being applied as Singapore shores up its defences, they said. They believe that unlike during Sars, Singapore is far more ready now.

LESSONS LEARNT

Singapore has had two brushes with pandemics in recent memory — Sars and H1N1.

While Singapore was able to contain and recover from both, the varying nature of the viruses, as well as the changes in medical science, meant that dealing with each required different approaches.

Doctors had limited options when treating Sars patients and could only administer supportive care, and there was nothing that could be done to prevent infection. In comparison, vaccines and treatment options were available when H1N1 claimed 18 lives in Singapore and infected more than 400,000 people, out of which about 1,300 had to be hospitalised.

- COMMAND AND CONTROL

Sars first arrived in Singapore in late February 2003, and was detected in a woman with an atypical pneumonia on March 1, 2003 at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH). At the time, no one knew how deadly and virulent it was and the first patient led to a cluster of 42 cases at the hospital.

A Ministry of Health (MOH) taskforce was set up on March 15, two weeks after the mysterious strain appeared in Singapore and three days after the WHO issued a global alert on the outbreak that began in Hong Kong.

But the command and control structure then was “wholly inadequate” in a crisis situation that was both fluid and unprecedented, a study in the Austrian Journal of South-east Asian Studies concluded in 2012.

The structure was led by the health authorities, when in hindsight, it required “more than a medical approach since resources had to be drawn from a number of government agencies that did not fall under the rubric of the MOH”, said authors Allen Lai and Tan Teck Boon, who were from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

They noted that it took five weeks after the first case was reported for the bureaucracy to adapt, though by then, the outbreak had already spread quickly out of TTSH.

On April 7, 2003, a national control structure was created in response to Sars, comprising a nine-member inter-ministerial committee led by then Home Affairs Minister Wong Kan Seng to provide strategic and political directions during health crises.

Helping to coordinate across silos were a core executive group of senior civil servants, and an operations committee spanning ministries. Their functions were later consolidated during the H1N1 crisis, which meant that this leaner bureaucracy was quicker to respond to emerging situations on the ground.

With the Wuhan coronavirus, observers told TODAY that it was evident that the Government had reacted more quickly than in Sars and H1N1 when it came to establishing a multi-disciplinary decision-making body.

Professor Ooi Eng Eong, an infectious diseases expert and virologist at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, noted that a multi-ministry taskforce on the Wuhan coronavirus was formed on Jan 22, several hours before the first suspected case came to the attention of the authorities at 10pm the same day. The patient — a 66-year-old Chinese national tourist from Wuhan — tested positive the next day, becoming the first confirmed case in Singapore.

“If you look at the response time, it is a fact that the ministerial committee formed before the case appeared, and we can see that a lot of systems are already in place, occurring across ministries and not as siloed as back then when Sars caught us all by surprise,” said Prof Ooi, who is also deputy director of the Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School.

The taskforce was formed to direct the whole-of-government response to the outbreak, coordinate the public’s response and work with the international community.

Jointly chaired by Health Minister Gan Kim Yong and National Development Minister Lawrence Wong, the taskforce comprises a cross-section of Cabinet ministers spanning various portfolios. They are:

Adviser: Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat

Mr S Iswaran, Minister for Communications and Information

Mr Chan Chun Sing, Minister for Trade and Industry

Mr Masagos Zulkifli, Minister for the Environment and Water Resources

Mr Ng Chee Meng, Secretary-General of the National Trades Union Congress

Mr Ong Ye Kung, Minister for Education

Mrs Josephine Teo, Minister for Manpower and Second Minister for Home Affairs

Mr Desmond Lee, Minister for Social and Family Development

Dr Janil Puthucheary, Senior Minister of State for Transport, Communications and Information

Dr Chia Shi-Lu, a Tanjong Pagar GRC Member of Parliament who chairs the Government Parliamentary Committee for Health, said that this time, the chain of command is clearer.

He noted that even before the taskforce was formed, the MOH had already begun tracking the outbreak in China at the start of the year. Temperature screening measures were put in place at Changi Airport from as early as Jan 3.

But the high political signature of the panel had led some to question whether too many cooks were spoiling the broth, Dr Chia noted. “In fact, some have asked me: Are we overdoing it?” he said.

“I believe it is very important for everybody to come into the picture — you have to, because at this early stage, (the outbreak) affects so many different parts and you need leadership from them, and you cannot rely solely on MOH to coordinate everything,” he added.

- INFRASTRUCTURE, CASE MANAGEMENT AND ISOLATION

While information about the Wuhan virus is still emerging, Singapore is not in the same position as in the initial stages of the Sars outbreak in 2003, where it was — in the words of then Health Minister Lim Hng Kiang — “flying blind”.

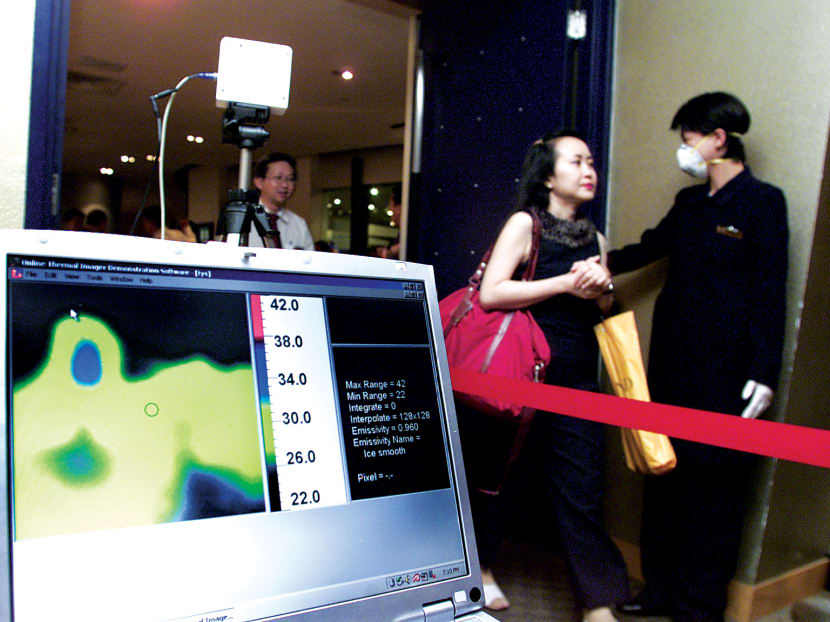

During the Sars crisis, Singapore only had two means to detect those infected with the virus: Their clinical symptoms and their travel history. Detecting these were not easy at the time as temperature screeners were also a rare resource, unlike today.

“We have to depend on people taking temperature, and we have to depend on people being truthful to us in their contact history,” said Mr Lim then, describing Sars as a tremendous challenge.

Dr Tan Yia Swam, First Vice-President of the Singapore Medical Association (SMA), said that in the Sars crisis, “there were too many unknowns, and precautions came too late, and too slowly”. Sars was zoonotic in nature, with the disease starting in animals before spreading to humans.

As a result, policies and procedures regarding risk stratification, contact mapping, contact tracing, quarantine and others were developed on the fly as the epidemic erupted, she said.

“Today, all of the above have been developed and tested before in exercises and they are now put into action. Of course, these plans, policies and procedures must be modified in line with the epidemiology of the disease, but we are not working from scratch, unlike the past experience with Sars,” she added.

Addressing the media on Monday, Mr Lawrence Wong said that in the taskforce’s national response to the virus, it is able to “marshal all available resources” to tackle the scourge.

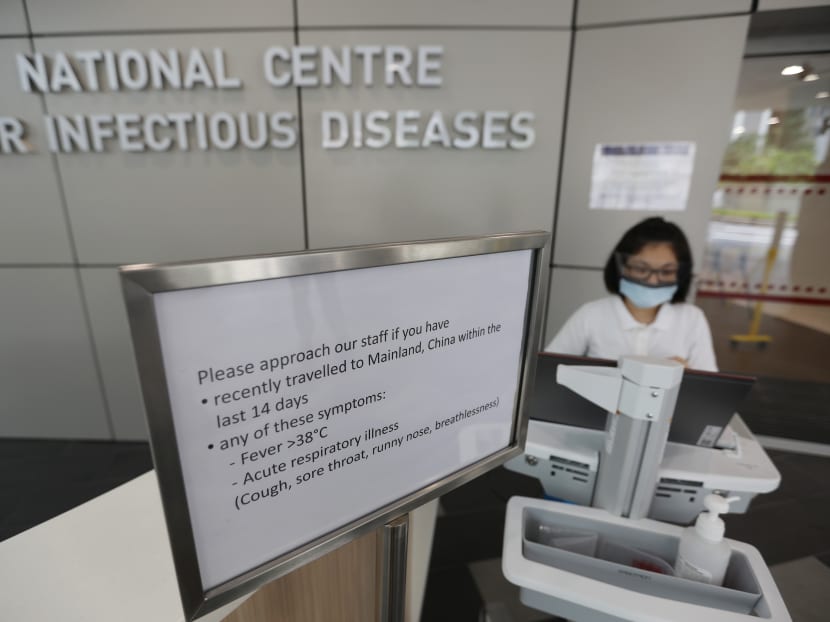

In terms of capacity, Singapore has already beefed up its healthcare and isolation capacity since 2003. This includes the 330-bed National Centre for Infectious Diseases that opened last year, and new hospitals such as Khoo Teck Puat Hospital in 2010, Ng Teng Fong General Hospital in 2015, and Sengkang General Hospital in 2018, he said.

During Sars, TTSH was known as “Sars Central”, the designated hospital to handle patients. This was borne out of a policy to restrict transmission of the virus to other hospitals, after a patient — who was unaware that he had been infected with the virus during his stay in TTSH — created a new viral cluster at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) when he went there for a surgical problem after his discharge from TTSH.

This policy changed in 2009 during the H1N1 outbreak, with the Health Ministry imposing a standardised infection control measure on all healthcare facilities, empowered by timely tweaks to the Infectious Diseases Act. More than 400 family clinics were made “H1N1-ready” and equipped with the Tamiflu vaccine to handle the outbreak.

Similarly, all public hospitals are capable of handling the Wuhan virus today, and come equipped with isolation rooms, which were in short supply in 2003.

When it came to medical supplies, Dr Chia recalled how there was hardly a stockpile of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers then, such as N95 respirators.

“Because an N95 mask needs to fit well for it to perform its function, having a properly fitted mask was (hard to come by) during Sars, and we had to find time to do the fitting too,” said Dr Chia, who was an orthopaedic surgeon at SGH at the height of the crisis.

“Today, most of us are already fitted with our own personal equipment, even as new staff. Everything is in place today,” he said.

For the general public, the Government will be disbursing a pack of four surgical masks to each of the 1.37 million Singapore households in a one-off exercise between Feb 1 and Feb 9. This was also done in 2003 when all households received a free emergency kit, containing N95 masks and themometers.

This time round, the mask distribution comes amid long queues at pharmacies around the island as people clamour to buy masks, and retailers say their stocks of surgical masks and N95 masks are running low or sold out. The Government had released 5 million masks from its stockpile over nine days to the retailers but they were all snapped up in hours.

Said Dr Chia: “The message is that there is enough for the whole of the population and in reserve too.”

SMA’s Dr Tan said his association met with the College of Family Physicians Singapore over the Chinese New Year weekend to carry out “complex logistics arrangements” to ensure that there is a steady supply of surgical and N95 masks to replenish stocks for the frontline healthcare workers.

“We are all monitoring the situation closely, and are ready to step up efforts when the need arises,” he said.

Experts noted that contingency plans have been put in place too — student hostels are converted into quarantine facilities in anticipation of future cases, and the Outward Bound Singapore on Pulau Ubin has been marked as a possible quarantine site.

TRICKY BALANCE IN THE FACE OF IMPONDERABLES

On Monday, Mr Lawrence Wong also called on Singaporeans to be psychologically prepared that the Wuhan virus could be worse than Sars given the many “imponderables” and “uncertainties” regarding the infection, though he stressed that there is still no evidence of community spread of the disease in Singapore.

Over the past week, however, the first reports of human-to-human transmissions outside of China have surfaced in Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam and Germany.

Mr Lawrence Wong said Singapore’s approach “is to anticipate and move as swiftly as we can”. “But every action we take really has to be based on evidence, data and international medical guidelines,” he added.

Unlike Sars, which impacted Singapore when little was known about it, there is now a greater understanding about the coronavirus, a family of viruses that include the Wuhan strain and Sars.

But data gaps still exist, said Professor Tikki Elka Pangestu, a visiting fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and a former director of the WHO’s research policy and cooperation department in Geneva.

Prof Pangestu told TODAY that not much is known of the proportion of mild and asymptomatic cases versus the severe and fatal ones, which currently makes it difficult to evaluate the Wuhan virus’ true epidemic potential and complicates the outbreak response.

There is also the worry that the virus could mutate into a more virulent and more highly transmissible strain. “This needs close monitoring and another data gap will be in how quickly this development can be evaluated,” he said.

Despite these gaps, Singapore has “reacted much more swiftly and comprehensively” than in 2003, Prof Pangestu added.

A rule of thumb for any country’s approach in health crises, he said, is to base decisions on scientific evidence and rational analysis in the context of its own capacities.

“I think the Singapore approach is the correct one given the current information and evidence available — robust but not over-reactive and flexible enough to accommodate new developments,” said Prof Pangestu.

He noted that overreaction risks imposing an unjustifiable burden on the country, potentially impacting normal daily routines and the livelihoods of certain vulnerable segments of the population. Underreaction, on the other hand, would lead to a more extensive spread of the virus.

“Calibrating the balance is tricky, but as I said, base your decisions on the existing scientific evidence,” said Prof Pangestu.

Prof Ooi from the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health added: “There is a risk and cost to overreaction and a cost to underreaction. Nobody knows what is the right answer and there is no hard science to it — this is a judgement call and there is no right or wrong.”

Where there is a dearth of knowledge on imported pandemic cases, Singapore’s national strategy is flexible with the changing circumstances, and the plan recommends taking border control measures that would “err on the side of caution with more intense efforts until such time when the disease profile becomes clearer”.

Addressing the media on Friday, Mr Lee said: “I think as a Government, in a way, we are overreacting because we are trying to look ahead to see what can go wrong and take preemptive steps to prevent that from happening.”

Within a week, the taskforce moved from allowing travellers from Wuhan to enter Singapore while subject to enhanced screening on Monday, to imposing a complete entry ban on all nationalities who have been to China in the past 14 days on Friday.

The Immigration and Checkpoints Authority has also stopped issuing all forms of new visas to those with People’s Republic of China passports.

HANDLING A PSYCHOLOGICAL CRISIS

Although the memory of Sars may have faded for some, experts say that the psychological lessons from it have remained until today, such that more Singaporeans are aware of the need to cooperate with the authorities during a health crisis.

For example, social media is rife with examples of Singaporeans calling out bad actors, such as online sellers who hoard surgical masks to resell, or profiteering behaviour by certain businesses. The Government has also acted quickly to combat such behaviour.

But Dr Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, believes that the Sars legacy can also be a double-edged sword: The prospect of another Sars-like epidemic might lead to needless panic, or worse, “kiasuism”.

In a viral outbreak, being “kiasu” means that people only think for themselves, preventing mutual cooperation from happening, he said.

Urging Singaporeans to do better, Dr Leong said they should be prepared for the viral outbreak but not overdo it. If fear and panic take hold, they can overwhelm the country’s response “like a tsunami”, he said.

This means Singapore’s national response has to preemptively address concerns that could lead to panic, he said.

“You have no time to get ready. Better to be ready (for the worst) now than not ready at all… There is little room for mistakes (that create more panic),” said Dr Leong.

Dr Chia believes that Singaporeans are generally behaving in a rational way so far, based on his conversations with residents as an MP or his interactions with patients.

“During Sars, there was a lot more fear and a sense of real danger for everyone. We had people trying to evade quarantine, refusing to cooperate or going for medical screening… But so far there are no cases of people who are trying to evade authorities, in other countries, yes, but not among Singaporeans,” he said.

The rise of social media, which was non-existent during Sars, can also give rise to disinformation that fuels further panic.

On the threat of fake news, SMA’s Dr Tan said: “Social media may do more harm than good in this kind of situation where fake news may spread faster than a virus and trigger unwanted behaviours. We urge all readers to exercise judgement when reading stories from various sources, and to keep referencing to official websites for accurate information.”

STRONGER LEGISLATION

Compared with the Sars crisis, Singapore has more legislative levers now to deal with fake news and anti-social behaviour — the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act being one of them.

Lesser known are the many enhancements to the Infectious Diseases Act over the years since 2003, which give the authorities greater powers to enforce orders that were issued in the fight against a gazetted outbreak.

The Act allows people who break home quarantine orders to be arrested without a warrant and to be jailed or fined on conviction. It was amended last year to allow officers to use “physical means” to enforce the order by bringing an absconder back to the place of isolation, in lieu of arrest.

It also makes explicit that persons under legal orders that restrict their movement in Singapore, would not be allowed to leave the country, unless otherwise permitted.

The breadth of such powers in Singapore gives the authorities the ability to ensure that evasion tactics, such as those described by Dr Chia, cannot happen again. The issue became such a problem during the Sars crisis that the health authorities had to resort to draconian measures, such as installing video surveillance cameras in the homes of people who were ordered to be quarantined.

The lack of legal powers has created some difficulties for several foreign governments in dealing with the Wuhan coronavirus. Earlier this week, two Japanese citizens who were brought back to Japan from Wuhan on a chartered flight declined to go for medical screening when they landed in Tokyo.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe told the Japanese Parliament: "While quarantine officers did their best to persuade them to go for further tests, they refused, and unfortunately there is no legal basis to force them to do so."

MORAL SUASION AND IMPORTANCE OF PUBLIC COMMS

But over the longer term, evidence suggests that government measures such as quarantine and travel restrictions are not as effective as instilling a voluntary sense of social etiquette and responsibility among the people.

Having a buy-in from the public is especially essential when the authorities need the people’s support to carry out certain measures, noted Prof Pangestu.

Prof Pangestu said: “You need the public’s cooperation for your measures to be successful, such as to follow good hygiene practices, be alert to any symptoms, promptly seeking healthcare, awareness of potential risks, and to counter the spread of misinformation on social media.”

This will be critical during the “surge response” — when situational changes cause a sudden need for the authorities to ramp up its measures, such as activating quarantine sites that are being held in reserve.

A lack of moral suasion would erase the ability for the Government to implement these measures, experts said. They noted how in Hong Kong, protestors bombed a general hospital and a residential building that the authorities had wanted to use as a possible quarantine facility.

Over the past week, South Korean protesters — mostly residents — also used tractors to block access to facilities earmarked as quarantine centres in the cities of Asan and Jincheon, which are about 80km from Seoul.

Experts said cooperation from the masses largely relies on public education as well as proper and accurate communication of risk, which is not always a guarantee considering the complex flow of information in a crisis situation that can lead to miscommunication.

An April 2003 article in The Straits Times, "All the right moves for Sars but info’s a bit slow, no?", by its then news editor Bertha Henson, described how the MOH was asked at a press conference to confirm a tipoff that SGH nurses might have Sars. The authorities said no, but it later emerged the next day that 21 SGH staff were on the Sars suspect list.

“The kindest thing I can say about this sudden announcement is that the ministry gets its information later than the media,” wrote Ms Henson then.

Referring to the incident, Professor Chee Yam Cheng, the current president of the Singapore Medical Council, wrote in a series of memos about Sars in 2003 that “quick dissemination of information — and accurate information — is almost as important as transparency in a health emergency”.

Prof Pangestu believes that in general, Singaporeans are united and support what the Government is trying to do to contain the situation.

“But public reaction is hard to control especially with fake news on social media. The idea that ‘perception is reality, anything is the truth’ often operates in this kind of (crisis) environment. That is why public risk communication is so important,” he said.