The Big Read: What the demographic ‘time bomb’ spells for S’pore’s education system

SINGAPORE — Just last month, Blangah Rise Primary School celebrated its 40th anniversary with pomp - there were student performances, a sumptuous buffet dinner and a video montage of the school’s milestones.

Primary 1 enrollment nationwide has been on the decline since 2000, when it peaked at over 50,000. This year, it fell to a record low of 37,500, statistics from the Ministry of Education (MOE) showed. TODAY file photo

SINGAPORE — Just last month, Blangah Rise Primary School celebrated its 40th anniversary with pomp - there were student performances, a sumptuous buffet dinner and a video montage of the school’s milestones.

But the school at Telok Blangah Heights could struggle to get to the half-century mark.

Like several schools across the island, it has been hit by falling Primary 1 enrollment. This year, it is running only two P1 classes, with fewer than 30 pupils each - a far cry from just a few years ago when there were at least five classes.

“I can’t help but think that our days are numbered. Merger might be on the cards for us,” said a female teacher who requested anonymity as she was not authorised to speak to the media.

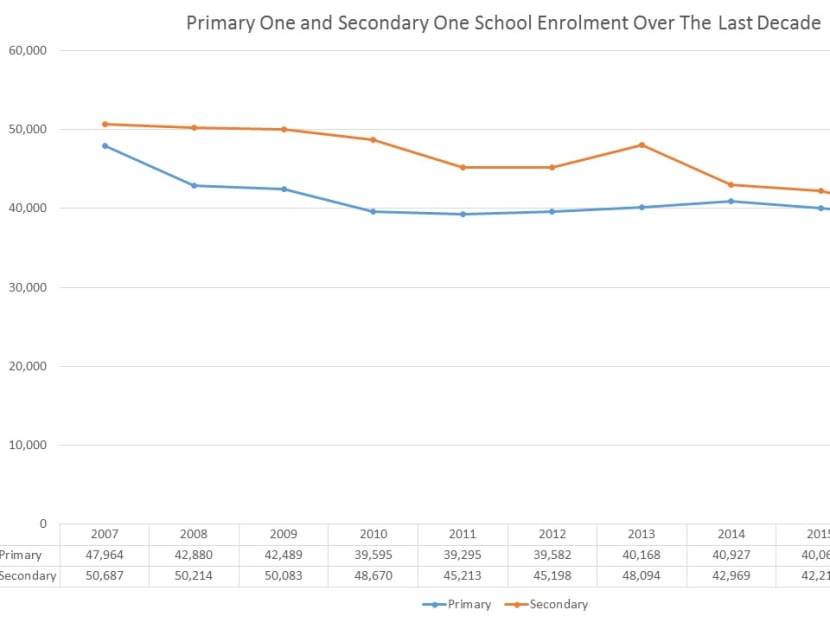

Primary 1 enrollment nationwide has been on the decline since 2000, when it peaked at over 50,000. This year, it fell to a record low of 37,500, statistics from the Ministry of Education (MOE) showed.

Similarly, the number of students entering Secondary 1 is on the slide. This year, about 35,000 pupils embarked on their secondary school education — the lowest since 1960, when enrollment was 20,842.

“Declining birth rates have led to overall falling student enrollments. Some schools in more mature estates are facing lower enrollment because of lower demand for school places in such estates,” said an MOE spokesperson.

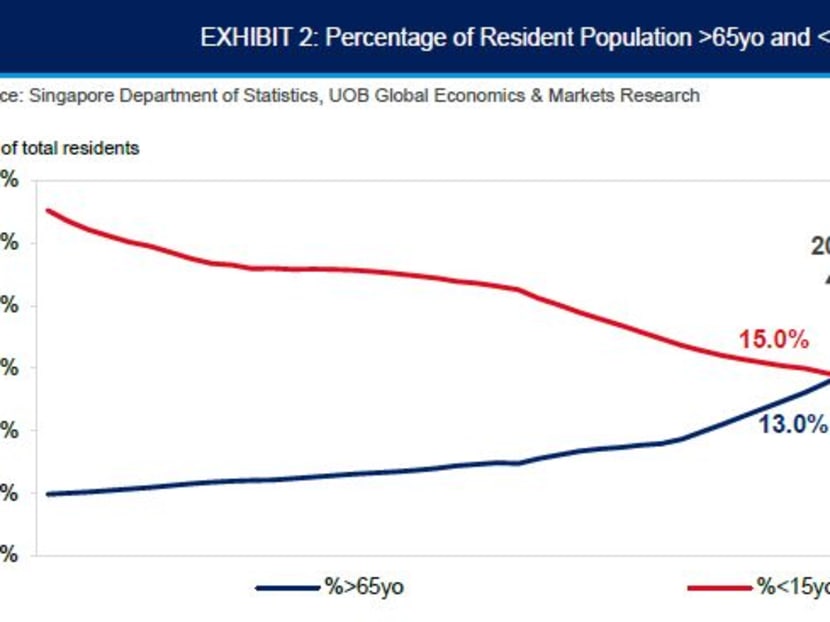

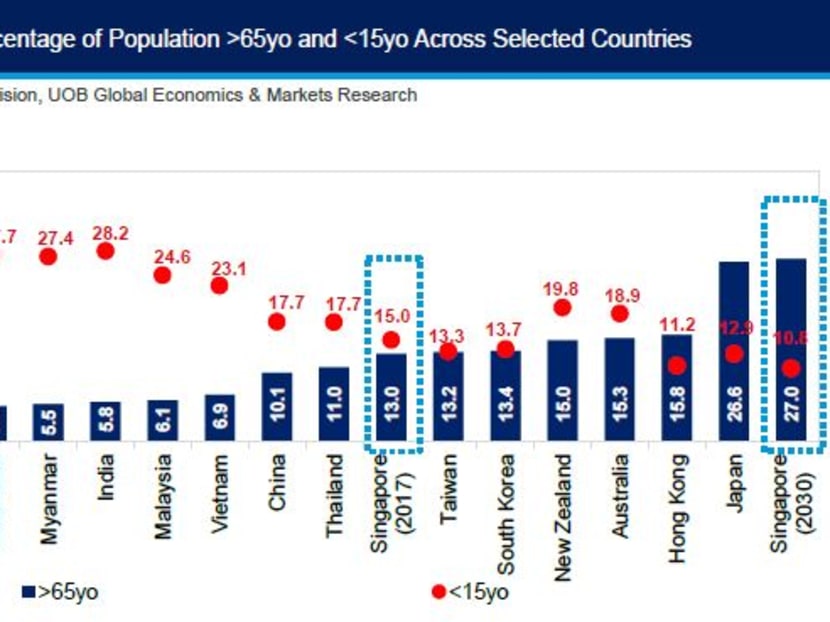

Singapore’s demographic challenge has been well-documented, and it came under the spotlight earlier this month, after a UOB report by economist Francis Tan warned that Singapore will cross a demographic Rubicon next year when the number of elderly here matches the youth population for the first time in the country’s modern history.

The demographic “time bomb”, as the UOB report called it, would have deep implications across Singapore’s entire education landscape including the formal school system and the tuition industry, said observers and experts whom TODAY spoke to.

On the flip side, will this mean schools can allocate more resources and attention to each individual child, particularly those who are socially disadvantaged? Will class sizes shrink? What would this mean for the booming tuition sector, and the preschool sector which has been expanding rapidly?

For now, the most direct impact is on schools’ enrollment, and this has fallen so sharply for some schools that they were subsumed by others.

The consolidation is necessary to ensure that schools here have a critical mass of students, allowing them to provide a diverse range of educational programmes and co-curricular activities (CCAs), MOE had previously said.

Primary schools that have seen enrollment tumble include Lianhua, Montfort, Si Ling and First Toa Payoh, for example. Interviews with teachers at these four schools said that while they used to have up to six or seven Primary 1 classes as recently as two years ago, the number fell by as much as half this year.

The MOE spokesperson said: “The enrollment figures for individual schools vary from year to year, as parental choices change.” The ministry regularly reviews the “demand and supply trends at the national and local levels to ensure that there are sufficient school places to cater to demand”, she added. “Our priority remains to provide our students with a good educational experience at schools that are accessible from where they live.”

Veteran educator Belinda Charles, who is the dean of the Academy of Principals, noted that school mergers had been going on for a while, even before the falling birth rate had an impact on cohort sizes. “That was when older housing estates became mature, the kids grew up and left for new town, leaving a smaller school going population (in the older estates),” she said.

In recent years, however, the mergers between schools have picked up pace as a result of the falling student cohort sizes.

In the last three years, MOE has merged three pairs of primary schools (in 2015), and 11 pairs of secondary schools (four last year and seven this year). At the same time, MOE opened three new primary schools last year.

Earlier this year, the ministry also announced the biggest school merger exercise to date, under which 28 schools — including, for the first time, junior colleges (JCs) — will be consolidated in 2019.

The MOE spokesperson said its school planning takes into account the current and projected cohort sizes, and planned housing development programmes to ensure sufficient school places to meet the demands of each residential area. “This may include plans to merge some schools in areas of lower demand, and to build new ones in areas of higher demand,” she said.

IMPACT ON STUDENTS AND TEACHERS

Early this year, students in Si Ling Primary’s badminton CCA were told that the school has decided to scrap the sport due to a lack of critical mass.

“Of course the students were disappointed. It is not their fault, neither is it the fault of the school,” said a teacher who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It is because of a macro-trend.”

Since 2015, the number of Primary 1 classes at Si Ling has dropped from seven to five, with the 36-year-old school facing stiff competition for students from the nearby Innova and Woodlands primary schools, said current and former teachers.

Meanwhile, prior to merging this year, Siglap Secondary and Coral Secondary had to discontinue several CCAs such as Red Cross and badminton.

Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC Member of Parliament (MP) Zainal Sapari, who was a Cluster Superintendent at MOE before joining politics in 2011, felt that it was time to look at greater collaboration among schools. For example, students could join CCAs in another school if their school do not offer these due to a lack of critical mass, he suggested. “I don’t think we should deny any pupil interested in a particular CCA just because of falling enrollment,” said Mr Zainal.

This may already be taking place at a different level, with the MOE-organised biennial Singapore Youth Festival tweaking its criterion for next year’s competition to allow school choirs with fewer than 24 members to participate. Such choirs can also combine with their counterparts from other schools if they wish to do so. This is in contrast to last year’s festival, which seeks to celebrate students’ CCA achievements, where points will be deducted from choir groups that have fewer than 24 members.

Apart from CCAs, the experts noted that the lack of critical mass could also affect academic programmes such as applied subjects in computing and electronics which are offered by selected schools, as well as the Applied Learning Programme (ALP) and Learning for Life Programme (LLP) which were rolled out in all schools this year. The ALP teaches students to apply learning in real-world settings, while the LLP seeks to instill life skills and socio-emotional competencies in the areas of sports or performing arts for instance.

Ms Charles pointed out that under Singapore’s education system, the current school structure depends on economies of scale. There is “less leeway in smaller schools” to offer a variety of CCAs and programmes if their enrollment numbers are small, she said. “There will be less of the big-scale projects simply because you cannot overload your now smaller staff numbers, though very often these productions did bring disparate parts of the school together,” she added.

There will also be impact on the teaching profession, said Ang Mo Kio GRC MP Intan Azura Mokhtar, who is the deputy chairperson of the Government Parliamentary Committee (GPC) for Education.

Currently an assistant professor at the Singapore Institute of Technology, Dr Intan was previously a secondary school teacher. She noted that teacher recruitment could fall further due to the shrinking cohort sizes and ongoing efforts to retain senior teachers longer. It was previously reported that annual teacher recruitment had dropped from a peak of 3,000 in 2009 to about 900 in 2015. As of last year, there was a total of more than 33,300 teachers in service.

On the hiring of teachers, the MOE spokesperson said the ministry “continues to recruit to replace teachers who have left the service, with a focus on recruiting more teachers in specific subject areas such as Art, Music, Humanities, Physical Education and Tamil”.

With school mergers possibly becoming more frequent, Associate Professor Jason Tan from the National Institute of Education (NIE) said that teachers will have to make “big adjustments” in areas such as content knowledge, teacher-student relationship and classroom management when they are redeployed to other schools in the wake of consolidation.

Teachers in JCs and some in secondary schools tend to specialise in a particular subject, making it hard to transition to the lower levels, said Assof Prof Tan who is from NIE’s policy and leadership studies department.

Nevertheless, Singapore Management University adjunct associate professor Kirpal Singh said this does not mean teachers eventually have to become generalists. Specialising allows them to understand the subject pedagogy better and come up with innovative teaching materials and lessons.

THE QUESTION OF CLASS SIZE

In view of the demographic shifts, it could be timely for MOE to explore reducing class sizes, experts and teachers said.

Last month, Workers’ Party Non-Constituency MP Leon Perera called for the ministry to conduct a “large randomised trial” in Singapore to examine the benefits of having fewer students in classes. Filing an adjournment motion in Parliament, he argued that international studies have found that small class sizes allow weaker students to be more engaged, and helps them develop soft skills such as confidence.

In response, Education Minister (Schools) Ng Chee Meng pointed out that class sizes are not indicative of the learning support and attention which students receive. He cited other factors such as exposing students to practical learning and encouraging them to have an “entrepreneurial dare” so that they can solve real-world problems creatively. “It is teachers, and how they teach, that make the critical difference, not just class sizes,” Mr Ng said.

Still, Mr R Sinnakaruppan, chief executive of consultancy firm Singapore Education Academy, noted that students in other countries such as Finland have benefited from smaller class sizes, and it is time for MOE to “take a hard look” at the issue.

Between 2011 and last year, teacher-student ratios in Singapore have dropped from 1:19 to 1:16 in primary schools, and from 1:15 to 1:12 in secondary schools.

MOE had reduced the class size for Primary 1 and 2 more than a decade ago, in recognition that students at these levels are of mixed ability and teachers have to cater to a wide range of pupil needs in each class. More individualised attention in these two foundational years of formal schooling can also help ground pupils strongly in literacy and numeracy required as a foundation to complex topics in later years.

Latest figures from MOE showed that the average form class size in primary and secondary schools last year was 33 and 34 respectively, while the class size for Primary 1 and 2 have been reduced to an average of 29 students per class, down from 40 previously.

A teacher from Lianhua Primary, who requested anonymity, said that it is “a good chance for MOE to do a big reassessment of the deployment of teachers”. Instead of posting some of them to the ministry, more teachers could be sent to schools to teach smaller classes, he said.

Weighing in on the debate, Assoc Prof Tan reiterated that there is no consensus among international researchers that smaller class sizes are truly beneficial, and the current system has been serving pupils well for the past decades.

He cited studies by Professor John Hattie, who is the director of the University of Melbourne’s Education Research Institute, which concluded that class size does not have a major influence on learning outcomes.

But given that no similar studies have been done in Singapore, some experts felt that MOE should consider conducting its own research. To this, Assoc Prof Tan said this could be tricky to execute. Among other things, a random study might raise questions among parents on why their children’s schools were or were not selected, he said.

Adding that private tuition which is pervasive here might also skew the results, he said: “That makes it harder to establish the co-relational link between class size and students’ performance that we’re looking for.”

WILL TUITION INDUSTRY SHRINK?

The falling cohort sizes could also stiffen competition in the billion-dollar tuition industry, particularly among less established agencies, the experts said.

Already, there have been casualties. The number of tuition centres registered with MOE had increased from about 500 in 2011 to about 600 last year. However, that figure has plummeted by a third to about 400 this year.

“This will be a continuing trend. It’s all about the survival of the fittest,” said Mr Sinnakaruppan.

While the industry could go through a period of consolidation, observers and experts generally believe that it will emerge unscathed, given Singapore families’ strong demand for private tuition and enrichment programmes.

Jalan Besar GRC MP Denise Phua, who chairs the GPC for Education, said the industry would adapt and find its own niches “to satisfy the cravings of parents with high expectations”.

For example, tuition agencies have sprung up over the years to help students get into secondary schools through the Direct School Admission (DSA) scheme — causing concern among the authorities that its objective is being compromised.

The scheme was set up 13 years ago to recognise and admit students based on talent in areas such as sports and the arts. “Unhealthy developments such as the rise of the DSA tuition classes, unless stopped, will dilute the efforts of MOE to place less emphasis on academic scores alone for secondary school admissions,” said Ms Phua.

Tuition agencies TODAY spoke with were unfazed by the potential impact of a falling student population, pointing to rising enrollment at their centres in recent years.

Mr Lim Wei Yi, who is the co-founder and managing director of Study Room, said that since its opening in 2014, enrollment has shot up from 30 to almost 500 now. Given the burgeoning demand, he intends to open a second branch next year.

Welcoming the stiffer competition, he said that it would be beneficial for the “better players as the less effective centres get weeded out”.

Similarly, Mr Tony Chee, who founded Best Physics Tuition Centre, said his student numbers have increased by 20 per cent in the past year, and he expects demand to grow by about 15 to 20 per cent in 2018.

“The dwindling student population is a headwind for the industry, but I feel that tuition centres and tutors who can deliver real value to students will still be sought after,” said Mr Chee, who was formerly a senior head of the higher education division at MOE and a Public Service Commission scholarship holder. “The overall pie may also not decrease due to growing demand from parents and students.”

NUMBER OF PRESCHOOLS STILL CATCHING UP

Despite the falling cohort sizes, the Government has been aggressively ramping up the number of pre-school places.

From now till 2022, 40,000 pre-school places will be added via new centres, bringing the total number to about 200,000. Anchor operators will run the bulk of these new centres, while MOE raises the number of its kindergartens from the current 15 to 50.

Observers and experts pointed out that the supply of pre-school places is still catching up with demand, especially in the newer estates.

Adding that there will not be excess capacity in the short to middle term, Ms Phua noted that as more parents are working, the need for childcare places will continue to grow.

Assoc Prof Tan said that MOE’s foray in the sector would also shake it up, and some players may exit the industry as they cannot compete with the MOE kindergartens whose fees could be more affordable.

It was also announced last month that from next year, students in 12 of the 15 existing MOE kindergartens will be given priority – under Phase 2A(2) – when they register for admission to the primary schools they are co-located with, under a pilot. Phase 2A(2) is the third of seven under the Primary 1 registration exercise, and is reserved for children whose parents and siblings have studied in that particular primary school, or whose parent works at that school.

Centres which are unable to compete could fold and supply could be reduced as a result, Assoc Prof Tan said.

Mr Zainal reiterated that greater competition in the pre-school sector would be beneficial if it “leads to more vibrant teaching and learning”. He expects falling enrollment in some pre-schools, particularly those in mature estates.

A principal at a PCF Sparkletots branch in the east, who declined to be named, told TODAY that the pre-school chain — which is run by the PAP Community Foundation — has merged some of its centres.

She said that the anchor operator constantly looks at the demand for its pre-schools, and would make the call to merge if there are cost pressures. “The changing demographics are inevitable, and there’s bound to be a decline in demand,” said the principal, who has been in the sector for two decades. “But that doesn’t mean we should cease operations completely. There’s still demand for infant care, so some of the pre-schools with low demand can make a switch towards that direction.”

TURNING CRISIS INTO OPPORTUNITY

While the falling cohort sizes pose a myriad of challenges for the education system, the observers and experts were quick to point out that it also presents opportunities to relook existing practices.

They reiterated that MOE has the building blocks of the system in place.

A surplus of teachers, coupled with smaller student population, may allow greater interaction during the learning process, Mr Sinnakaruppan said. More resources could also be freed up to experiment with new approaches, he added.

Mrs Carmee Lim, 77, who was the principal of Raffles Girls School for 12 years, said policymakers could use the chance to move away from summative assessments, where students are evaluated solely based on their exams and are issued grades that “indicate whether they are smart or not”.

Instead, formative assessments should be adopted, said Mrs Lim, who is now mentor principal at pre-school operator MindChamps. Under such assessments, students would be evaluated through various methods such as project work to know whether they have truly understood a subject. “We are still stuck in learning content, or memorising content. We need more experiential learning where creativity would help students absorb knowledge,” said Mrs Lim, who was also previously a senior inspector of schools at MOE. “Why the polytechnic students are doing well is because they are engaged with the content through many ways, and that’s how they learn (to) solve real world problems. Why can’t we do that with our schools?”

While the education system has been working for the last few decades, it does not mean Singapore “should rest on our laurels”, said Mr Sinnakaruppan.

“We should try and switch things up. The falling enrollment, in a way, gives us a good opportunity to start afresh and rethink how we can reinvigorate learning experiences,” he added.

Similarly, Assoc Prof Singh felt that experimenting more with new pedagogies which are not so academic-centric would better equip students for a future that is set to be far more disruptive. “Many would resist change, but in the longer term, we would be the better for it,” said Assoc Prof Singh. “An experiment can sometimes fail. But by the same token, if the method is well-conducted, (it) can result in very beautiful achievements.”

Still, the way forward for the education system would necessitate a mindset shift.

For example, parents tend to perceive schools with low enrollment as “unpopular”, said Ms Charles. “There is the suspicion that it can’t be a good school if people aren’t coming to it,” she said. Such a perception would create a vicious circle, further reducing enrollment, she noted. “It might be time to change the thinking (from) ‘big is better’ to ‘small is beautiful’,” she said.