Dissecting ex-CJ Chan Sek Keong’s paper on 377A: What it says, what it doesn’t say, and what next

SINGAPORE — For the past week, the legal fraternity has been abuzz with excitement over a paper by former chief justice and attorney-general Chan Sek Keong, which argued that Section 377A of the Penal Code, when seen as against gay sex, is unconstitutional.

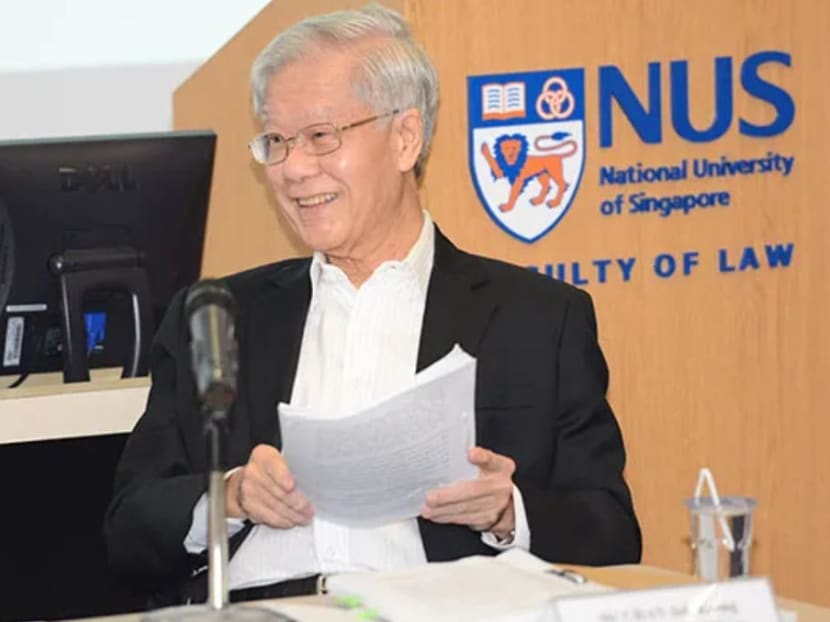

Former chief justice Chan Sek Keong (pictured), who was appointed National University of Singapore's first Distinguished Fellow in the Faculty of Law in 2013 after he retired from legal service, has written a paper on the much-talked-about Section 377A of the Penal Code.

SINGAPORE — For the past week, the legal fraternity has been abuzz with excitement over a paper by former chief justice and attorney-general Chan Sek Keong, which argued that Section 377A of the Penal Code, when seen as against gay sex, is unconstitutional.

As law academics and practising lawyers pore through his densely-worded 72 pages of analysis, titled Equal Justice Under The Constitution And Section 377A Of The Penal Code, they told TODAY that the paper was not only thoroughly researched and accurate, it also contained a number of arguments that have not been raised before.

These novel arguments in the paper — which range from the historical basis of the provision which sets out its original purpose as well as how the law should be and has been interpreted — should not be taken lightly, they added.

“Usually, judges are quite reticent about their personal views on public policy, knowing full well that their public statements carry great weight,” said Mr Genesis Shen, director of Templars Law.

Even more so for someone with Mr Chan’s credentials, he added. Mr Chan had served as Singapore’s apex judge for six years, and was the top-ranking prosecutor and legal adviser to the Government for 14 years before that.

Yet the repeal of the provision, which has in recent years attracted louder voices calling for or against it, does not seem to be the objective of Mr Chan’s paper, they said.

BACKGROUND

On Feb 20, at a closed-door seminar held by the National University of Singapore (NUS) law faculty, Mr Chan spoke about past judicial decisions in constitutional challenges of Section 377A by two individuals: Lim Meng Suang and Tan Eng Hong.

Although it was a private session, law students had diligently taken notes of Mr Chan’s arguments. These notes were shared among students and also with those outside of academia, and they eventually reached lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) advocates, including Dr Roy Tan, a 61-year-old retired general practitioner and a former organiser of the Pink Dot event.

The arguments presented at the seminar and circulated in the students’ notes mirrored those within Mr Chan’s latest paper.

Dr Tan and his lawyer M Ravi decided to file a constitutional challenge in September, and they will submit Mr Chan’s paper as part of their case, which is set to be heard in November — along with two other court challenges filed by deejay Johnson Ong Ming and Mr Bryan Choong, former executive director of non-profit organisation Oogachaga.

MR CHAN’S ARGUMENTS

Several lawyers, who are unconnected to the court challenges, discussed with TODAY some of the main legal arguments in the paper that led to Mr Chan’s conclusion about the constitutionality of Section 377A.

Argument 1: The original purpose of Section 377A was to curb the social problem of male prostitution, but its offences do not overlap with neighbouring provision Section 377. When Section 377 was repealed in 2007, the original purpose of Section 377A was “impliedly repealed” as well.

What the paper said:

Enacted in 1938 before Singapore’s independence, Section 377A was meant to deal with the rising trend of male prostitution, as existing laws were insufficient.

Section 377 had covered penetrative sex acts against the order of nature, while Section 23 of the Minor Offences Ordinance, which covered non-penetrative sex acts in public, were inadequate to deal with male prostitution.

Section 377A was also drafted such that its offences are not those covered under Section 377, and this was stated in an explanatory note.

In 2007, Parliament passed a Bill to amend the Penal Code, repealing Section 377 and adding Section 376 and its neighbouring provisions. Section 376 covers penetrative sexual assault, with a sub-section penalising males who sexually penetrate another unconsenting male.

In essence, the legislative history of Section 377A means that it covers only non-penetrative gay sex acts of a grossly indecent nature.

Mr Chan concluded that when Members of Parliament debated the Bill, they had therefore misunderstood the scope of Section 377A and thus debated incorrectly on the basis that the provision covered consensual gay penetrative sex.

What lawyers said:

NUS adjunct professor Kevin Tan, who had moderated the February seminar, agreed with this conclusion. He also noted that in the Lim Meng Suang case in 2014, the appellate court had judged that Section 377A covered gay penetrative sex acts, yet it had also referred to the same explanatory statement that led Mr Chan to conclude otherwise. “This is one of the big puzzles,” said Dr Tan.

Singapore Management University (SMU) law don Eugene Tan said that the drafting of Section 376 and 377A in 2007 could have been made clearer, with Section 376 dealing with no consent and Section 377A dealing with consent.

However, he argued that what happened in 2007 could also be seen as a “refreshing” of the law, including of 377A — even if it was not affected by the changes. “Put it another way, from the parliamentary debates, it is clear that Parliament did not seek to do away with the offence of consensual sex between men,” said Associate Professor Tan.

SMU Assistant Professor of Law Benjamin Joshua Ong also said that Parliament could have changed the purpose of Section 377A in 2007. Said Assistant Prof Ong: “I suppose that (Mr Chan’s) argument is quite sound — in theory, Parliament could have changed it if it wanted to, but he is right that Parliament didn’t, because the matter wasn’t put to a vote.”

Argument 2: Subsequent court proceedings and judgments made were based on an incorrect reading of the type of offences that Section 377A covered after the 2007 amendment.

What the paper said:

After the 2007 Bill was passed, there were three court proceedings that involved Section 377A. Mr Chan wrote: “It would appear that Section 376(1) or its legislative effect also escaped the attention of (the defence) counsel and the courts in the three proceedings, since there is no discussion of these issues in the judgments.”

The judges found that Parliament, as well as the pre-independence Legislative Council, had intended for Section 377A to criminalise consensual gay penetrative sex, and that Parliament had decided to retain this legislative effect in 2007 by keeping Section 377A and repealing Section 377.

He said these three decisions could have been given “per incuriam” (Latin for “through the lack of care”). Therefore, they cannot be binding on future prosecutions for penetrative and non-penetrative sex under Section 377A.

What lawyers said:

SMU’s Assoc Prof Tan said it does not mean that the decisions in these cases — involving Lim Meng Suang and Tan Eng Hong — are currently non-binding, as a Court of Appeal in future cases must first rule that the earlier cases were decided based on an incorrect reading of Section 377A.

NUS’ Dr Kevin Tan said: “The Court of Appeal may have been wrong (then), but this remains good law till overruled by another Court of Appeal decision — which might happen sooner rather than later.”

Templars Law’s Mr Shen added: “Any interpretation of ambiguous wording of the law would be done by the courts. However, if the courts arrive at a conclusion that Parliament disagrees with, then Parliament may simply act to remove the ambiguity.”

Argument 3: In Singapore, with its diversity of people and religions, disapproval of male homosexual conduct per se by Parliament or a conservative section of society is not, in itself, sufficient legal basis to discriminate against male homosexuals and to deprive them of their constitutional right to equality.

What the paper said:

Based on the judgment in the Lim Meng Suang case, the courts had understood that gay sexual conduct is unacceptable to Singapore society.

Mr Chan said if this is true and is the sole reason for the law, it would give rise to questions about whether the criminalising of private consensual penetrative sex between males is reasonable, in that it “serves or advances a legitimate state interest”. These questions were not addressed by the judge.

The Government’s decision to not enforce Section 377A for consensual gay sex undermines the argument that the law should criminalise such conduct because it was seen as unacceptable or not desirable.

In itself, disapproval of gay sex by Parliament or by a conservative section of Singapore society is an insufficient legal basis to discriminate against gays. “Such purpose does not advance or serve a state interest that outweighs the constitutional right of equality before the law,” said Mr Chan.

Adding that constitutional rights are not majoritarian rights unless expressively qualified or restricted in the Constitution itself, Mr Chan said: “They cannot be curtailed or taken away by the majority in society only because the majority of society may disapprove of or find such conduct unacceptable on the basis of their moral values.” The Constitution acts as a bulwark against majoritarian demands, he said.

Mr Chan argued that Section 377A is the only criminal law in Singapore that is specific to a gender, and that any law which discriminates against one group of persons as against another must be justified. Since Section 377A has lost its original justification to curtail male prostitution, the provision can be seen as unconstitutional.

What lawyers said:

SMU’s Assistant Prof Ong said that while the Constitution does protect against majoritarianism, people would still find it contentious that Mr Chan could argue that disapproval by Parliament or by society should not be a legitimate basis for a law. “I thought this was an interesting argument,” he said, adding that the courts themselves had also argued in past cases that they were not entitled to question the legitimacy of law based on morality.

Assistant Prof Ong added that he believes that morality should not be the sole basis of legislation, otherwise one person’s set of morals will rule over that of another person. But the Singapore Constitution allows for morality, such as in Article 14 on the freedom of speech, assembly and association, and Article 15 on the freedom of religion. “You can have laws motivated by morality alone,” he said, though he is not aware of any case that has challenged the law based on morality.

NUS’ Dr Tan agreed that discriminatory laws need to be justified, otherwise it will run afoul of the Constitution, which states that all persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal protection of the law. He explained: “A law whose legislative object is to criminalise immoral or lewd behaviour in public will (not be constitutional) if it targets males only because females are equally capable of lewd and immoral behaviour in public.”

Dr Tan added: “We should understand this argument in view of another of Chan’s arguments, that mere intention to criminalise something cannot constitute a legislative object. Criminalising a particular act or behaviour is only a means to achieving an end and cannot be the object itself.”

WHAT NEXT

But lawyers said the paper does not address whether Mr Chan is speaking out in favour of repealing or retaining the controversial provision. It also does not address the role of Parliament to unravel this legal tangle of Section 377A. Hence, the paper’s conclusions may be unsatisfactory for some groups, they said.

Former attorney-general Walter Woon told TODAY: “Saying that penetrative gay sex is legal will not make the anti-gay lobby happy. Keeping Section 377A will not make the LGBT community happy either.”

The paper, however, does offer a way for Section 377A — a pre-1965 statute — to be read in a way that makes it constitutional. This can be done by limiting its scope to non-penetrative sex and applying it to women as well.

Lawyers suggested four possible outcomes:

Parliament can enact a new law that clearly criminalises consensual gay sex, thereby removing the ambiguity of Section 377A.

Parliament can repeal Section 377A.

Parliament does nothing, but the courts may agree with Mr Chan’s views on interpreting Section 377A in the way he suggested. However, a differently constituted Court of Appeal may still be able to reverse the decision in future.

Parliament does nothing, and the courts once again uphold Section 377A as constitutional.

But Professor Woon believes it is up to Parliament to make the call. “Ultimately, (it) must decide,” he said.