Explainer: How mRNA vaccines can grant long-term immunity and why search for a ‘super shot’ against Covid-19 carries on

SINGAPORE — It has been more than six months since the first vaccines were approved to fight Covid-19 and a growing body of scientific literature around the world are increasingly indicating that messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines grant immunity that could last for years.

A box of Comirnaty vaccines by Pfizer-BioNTech at an outdoor vaccination centre set up by the French Red Cross in Paris.

- Studies are showing that mRNA Covid-19 vaccines could grant long-term immunity

- A recent Missouri study in the US was the first to find direct evidence of a persistent immune response against Covid-19 following mRNA jabs

- This is a sign that immunity could last for years, experts said

- Work still cannot stop on vaccines because the Sars-CoV-2 virus is evolving

- The development of polyvalent “super shot” vaccines is a possible end goal

SINGAPORE — It has been more than six months since the first vaccines were approved to fight Covid-19 and a growing body of scientific literature around the world are increasingly indicating that messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines grant immunity that could last for years.

In April, a longitudinal analysis of 44 post-vaccinated individuals in Pennsylvania, United States, found not just significant antibody levels, but also strong indications that the body can remember how to react during a future infection.

In May, a study of 22 vaccinated people from Italy also had similar findings. That same month, a New York study of 63 people suggested that immunity could be very long-lasting, even against variants of concern.

Most recently, on June 28, a team of researchers in Missouri in the US released their longitudinal study of 41 vaccinated individuals that found convincing signs of long-term immunity.

The latest study went a step further to extract and test samples from lymph nodes — a critical component of the body’s immune system that trains cells to fight infections — to determine whether these sites were still active nearly four months after vaccination.

To find out what it all means, TODAY interviewed immunologists from the National University of Singapore’s Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine to understand what the science is saying about these vaccines.

Associate Professor Veronique Angeli from the school’s department of microbiology and immunology said that these findings are potentially important for the understanding of longer-term vaccine-induced immunity for Covid-19.

“This (Missouri) study tells us that the long-term immunity (to the strain that was first detected in Wuhan) is likely to be pretty good,” Assoc Prof Angeli said.

THE B & T OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

In a nutshell, vaccines grant immunity by teaching the body how to react to the Sars-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Traditional vaccines do so by injecting a “dead” virus into the body, while mRNA vaccines work by enabling the human body itself to reproduce harmless parts of the virus for the body to fight off the disease.

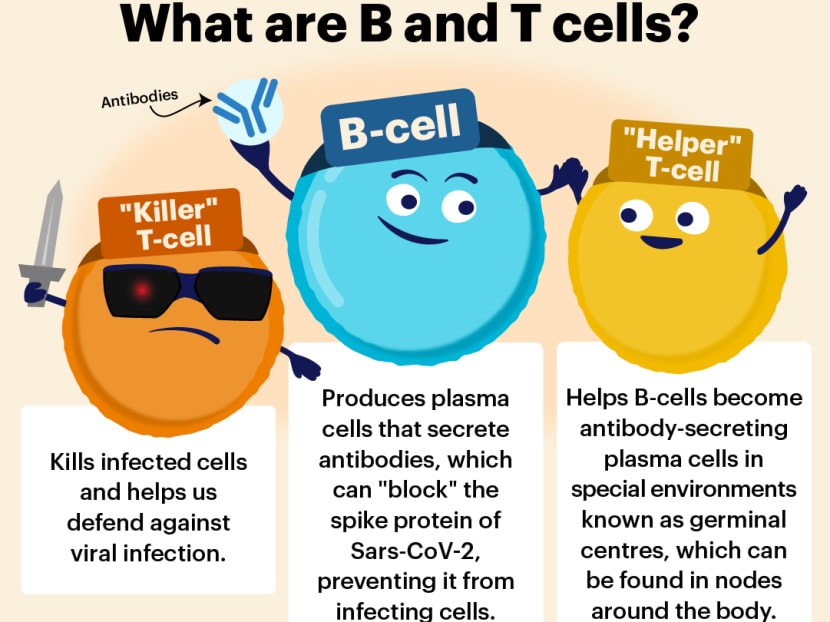

The goal of vaccines, in simplified terms, is to allow the body to produce antibodies that can shield against the “spike” proteins of the Sars-CoV-2 virus. These spikes are what allow the virus to infect human cells.

“The major function of (these) antibodies during a viral infection is to neutralise the virus by preventing it from infecting the host cells,” Assoc Prof Angeli and her colleague Paul MacAry said. Associate Professor MacAry is from the school’s Immunology Translational Research Programme.

And if the body can remember to do that for a long time, such as for years or a lifetime, that indicates long-term immunity.

This is why scientists are looking at lymph nodes and the bone marrow.

Within lymph nodes are “special training schools” known as germinal centres, which train “B-cells” to become long-lived antibody factories known as plasma cells.

There are also “memory” B-cells generated at these schools, which can remember the virus and lead to a more robust and rapid antibody response the next time the virus appears, the immunologist explained.

Also essential are “T-cells” that, like the B-cells, are another type of white blood cells that form a core part of the immune system.

“Helper” T-cells, in particular, contribute by helping B-cells become plasma cells.

WHAT THE STUDIES SHOW

The Missouri study, in particular, sought to determine how active these training schools in the lymph nodes remain over a period of time post-vaccination.

Among the 41 people recruited in the St Louis area, researchers extracted samples from the lymph nodes — which can be found in the armpits— through a fine needle. This was done at various times: At the third, fourth, fifth, seventh and 15th week after the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

The NUS immunologists said that this was an uncommon process in immunological research. It is also a difficult process to collect such samples, especially if samples have to be taken from the bone marrow.

Nevertheless, the study found high frequencies of germinal centre activity for at least three months after the second dose of the vaccine.

The immune response was found to be better for those who had had Covid-19 before and were also vaccinated.

This is the first study to provide direct evidence of a “persistent” B-cell response to the Sars-CoV-2 virus after vaccination, the Missouri researchers said.

Normally, germinal centres peak one to two weeks after inoculation and then start to wane within five to seven weeks, the researchers added.

IMPLICATIONS ON IMMUNISATIONS

For other viral pathogens such as Ebola and influenza, a strong germinal centre response of up to 15 weeks, as the study showed for Covid-19, has been linked to much longer immune responses — measured in years, Assoc Prof Angeli and Assoc Prof MacAry said.

“In other words, previous studies on other viral pathogens have shown that a strong germinal centre B-cell response is directly linked to the development of good Immunological memory and the development of long-lived antibody secreting plasma cells in bone marrow niches,” they said.

This could mean the same for Sars-CoV-2, though future studies are needed to verify this assumption.

The results of the latest study suggest that for most people with strong immune systems, a third booster shot may not be required at all.

Previous studies, such as those from Italy and Pennsylvania, have also suggested that those who had been infected with Covid-19 before and have since recovered have a greater immune response when they get the mRNA jab.

For this group, they may only need a single shot of an mRNA vaccine to achieve long-term immunity, instead of two.

If the original strain of the virus were the only viral variant that scientists had to worry about, “then a clear requirement for future booster shots would be unlikely,” the NUS immunologists said.

POLYVALENT VACCINES: AN END GOAL

However, the situation now is made complicated by new mutations such as the Beta and Delta variants, the experts said.

Evidence is also growing that the current circulating strains of Sars-CoV-2 can evade vaccines. The virus is still mutating as well, raising the likelihood of immune escape.

This is why booster shots are still being considered.

In the longer term, the hope is that boosters can be updated to tackle more, if not all, variants of the Covid-19 coronavirus.

Doing so could mean developing a polyvalent vaccine — a “super shot” designed to grant immunity to all mutant strains of the virus.

“In simple terms, these are cocktails of two or more target viruses (or antigens) in a single vaccine shot. For example, the seasonal Influenza vaccine usually contains three different forms of inactivated influenza viruses to engender broader protective immunity against the main circulating strains,” the immunologists said.

Other examples of polyvalent vaccines used in Singapore include the jabs for polio, MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) and DTP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis). Both the diphtheria and measles vaccines are compulsory by law.

On Tuesday, the global Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations called for the creation of such a vaccine against coronaviruses, since Covid-19 is unlikely to be the last.

This reality is also why some scientists are looking at vaccines that can jog a strong T-cell response as well, reports said.

A type of white blood cells known as “Killer” T-cells can seek out parts of the virus that hardly mutates and destroy them, which is a different approach from a B-cell response that produces antibodies to “block” the spike proteins of Sars-CoV-2.

In many variants, mutations at the spike protein have made it more difficult for vaccines to work as designed.

In May, a preprint of a Massachusetts study found that mRNA vaccines were able to trigger a T-cell response. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

As Dr Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious disease specialist at Rophi Clinic, told TODAY: “We need to remember that immunology has at least two arms — B-cells (that produce) antibodies and T-cells (that create) cell-mediated immunity.

“Having one helps. Having both is potent,” he said.