'It's like a lottery': Why these 'species hunters' spend days looking for fishes in S'pore waters

SINGAPORE — Visitors to Marina South Pier or Bedok Jetty at East Coast Park on a weekend may find themselves greeted with an unusual sight: Three young men fishing, photographing their catch at different angles, before releasing it back into the sea.

From left: Anglers Aidan Raphael Keh, Sim Jin Heng and Lin Jiayuan. The three regularly meet to go “species hunting” in the waters around Singapore.

- While many casual anglers fish for food, Aidan Raphael Keh, 17, Mr Lin Jiayuan, 21, and Mr Sim Jin Heng, 26, belong to a small community of “species hunters” in Singapore

- Species hunters, a niche group within the wider sport of fishing, prioritise catching a wide variety of fish species, over catching the biggest or most fish

- They do so for several reasons – such as to study the local fish species and marine biodiversity, to contribute to science and research, and the thrill of discovering species that were previously unrecorded in Singapore’s waters

- The three anglers said that they release more than 90 per cent of their catch, after documenting them

- The remaining are either retained for personal consumption or donated to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum for research purposes

SINGAPORE — Visitors to Marina South Pier or Bedok Jetty at East Coast Park on a weekend may find themselves greeted with an unusual sight: Three young men fishing, photographing their catch at different angles, before releasing it back into the sea.

While many casual anglers fish for food, Aidan Raphael Keh, 17, Mr Lin Jiayuan, 21, and Mr Sim Jin Heng, 26, belong to a small community of “species hunters” in Singapore.

A niche group within the wider sport of fishing, species hunters prioritise catching a wide variety of fish species, over catching the biggest or most fish.

“We have more fish species in Singapore’s shores than even far larger countries like Great Britain because we are in close proximity to the Coral Triangle, and we are in a biodiversity hot spot,” said Mr Lin, a bioengineering student at the Nanyang Technological University.

The Coral Triangle is a global epicentre of marine biodiversity, encompassing six countries – Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste.

The trio estimates that there are fewer than 30 species hunters locally.

‘LIKE A LOTTERY’

In some ways, species hunting is not too different from its main sport.

Like other anglers who try to understand the fishes and what they bite, in hopes of catching more of such species, the trio devote a significant amount of time to studying their targets – though they take this research up a notch.

This could look like hours spent poring over literature to better understand the fishes’ biology and ecology, or experimenting with different baits and angling techniques.

Unlike other anglers, however, they also document their findings in a “lifelist” – an informal, personal document recording every species they have caught on line-and-hook.

They admit that some people might not understand why they do it.

“People would say, ‘Wah, you spend how many days just trying to catch one fish, or some small fish with no value.’ They don’t see any value to it, so I guess we are a bit crazy,” said Aidan, a student at Victoria Junior College.

Mr Lin said: “It’s like a lottery – if you are just blind casting and suddenly, something new comes up. And if you are targeting something, you get an immense sense of accomplishment when you actually finally catch the new species.”

Asked why they were personally drawn to species hunting, the three anglers attributed this to a variety of reasons – such as to study the local fish species and marine biodiversity, to contribute to science and research, and the thrill of discovering species that were previously unrecorded in Singapore’s waters.

“I can observe whether the species is doing well. It allows us to have confirmation that a particular species is still native to Singapore and its population is not decreasing,” said Aidan.

Agreeing, Mr Sim, a specialised engineer, said: “Our waters around Singapore are not the same as what it was 10 years back, or five years back, or even two years back. So the fishes you catch nowadays are pretty different from what you could catch a few years back.

“So it’s pretty interesting to see the transformation now and within the years. I’m very excited to see what kind of species is coming into our waters.”

For Aidan, species hunting also allows him to get up close with marine life, which he loves.

“I’ve always had an innate interest in marine life since young, and I guess I never really grew out of it. I’ve always wanted to see the marine fauna in Singapore in person, not just in pictures,” he said.

“(Species hunting) allows me to have a greater sense of appreciation for the piscine-fauna here in Singapore, which are rather unappreciated because of their small size.”

On how they determine where to fish during their expeditions, Mr Lin said they rotate between a few places.

“To choose the places to catch the species, we mainly evaluate our target species, which types of habitat they will likely be found in, and sometimes we just pinpoint the location where they have been sighted before,” he said.

“So the locations that we go to vary a lot, but some consistent ones that we keep going back to will likely be St John’s Island, Lazarus Island, Bedok Jetty, Pulau Ubin, mangroves and this place – Marina South Pier.”

‘MUCH MORE TO DISCOVER’

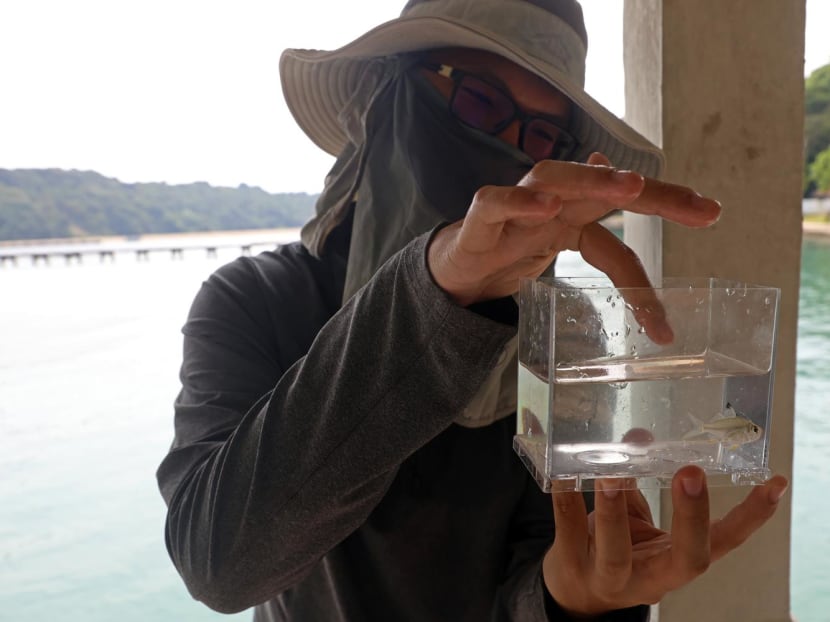

The three anglers said that they release more than 90 per cent of their catch. All juvenile fish are also released.

They also ensure to practise “proper fish handling”, such as keeping the fish in water, or wetting their hands when handling them so as not to damage their protective slime coat.

While most fish are released after they are documented, a small proportion are either retained for personal consumption or donated to the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum for research purposes.

“Through this process of fishing for species, we actually do come by species that have not been recorded in Singapore for a while, or have entirely not been recorded in Singapore at all,” said Mr Lin.

When this happens, they connect with local ichthyologists to tell them about what they have caught.

The findings are sometimes published in Nature in Singapore – an online journal by the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

They may also be retained and contributed to the museum, where they are preserved as specimens.

“Sometimes we catch rare fish that the museum lacks specimens of, and we will donate it to them. Hopefully, it will help to further the understanding of Singapore’s piscine biodiversity as a whole, in our research scene in Singapore,” said Mr Lin.

One thing the anglers have noticed is that the marine habitats have changed over the years, which they believe could be attributed in part to dredging from land reclamation, thus affecting the different fish species found in Singapore’s waters.

As such, the trio hope that their donations could contribute to the long-term studies and documentation of local species. With formal documentation, they hope to also be able to observe trends in the fish populations over the years.

This would be especially helpful in the event that these native fish dwindle in population, or cease to be found in future.

Mr Lin added: “I will say that even if they don’t use it for research in the near future, even just the specimen being there is a great aid to Singapore’s biodiversity research, because it actually shows that the species has been found here.”

This had been an issue with some older records which lacked specimens, because it meant there was no way of confirming the species’ existence in Singapore’s waters, outside of the researchers’ written accounts.

The hobby is one the anglers foresee themselves being hooked on for a long time.

“I’ve always had an innate curiosity with marine life, specifically fish. And I don’t think I can ever reach a point where I’m complete, I don’t have any more questions, or I understand every single thing about them,” said Aidan.

“We are situated near the Coral Triangle and our diversity is unparalleled compared to other countries. So it’s kind of a waste to be here (in Singapore), and to not appreciate what cannot be found anywhere else.”

And while the trio have each caught more than 300 species of fishes to date, Mr Lin said: “There is much more for us to discover, and it is all part of this hobby that we are unlikely to give up at all.”