How do we learn to read and write?

This is the time of the year when students take examinations, where reading and writing are essential elements to performing well. Yet, many individuals have trouble reading and writing due to a condition called dyslexia.

This is the time of the year when students take examinations, where reading and writing are essential elements to performing well. Yet, many individuals have trouble reading and writing due to a condition called dyslexia.

Those who are dyslexic experience difficulty taking examinations, which are currently not designed to judge them well. So how can we help these individuals? How do we learn language and what can happen when something in the process goes wrong?

THE ROLE OF PHONEMES

Learning to read and write in a language is not that simple. Most languages have about 40 sounds called phonemes. These are non-identical units of sound that are used in a language.

When a baby is born, as long as his hearing apparatus is intact and functional, he can hear and discriminate between these various phonemes.

The more a baby hears a particular set of phonemes, the more he learns to focus and discriminate between those phonemes that he commonly hears and not others. The baby has to figure out the set of phonemes that he has to learn.

This narrowing of focus happens within the first year of life among most infants. Thus in an English-speaking household, the baby will show greater identification and differentiation of English phonemes in contrast to a Mandarin-speaking home.

These auditory experiences become stored in memory and are the foundation of language development as the baby begins to relate the pattern of phonemes to objects and, over time, to tasks.

When the baby slowly attempts to talk and mimic the sounds that he hears, he uses these memories to drive the vocal apparatus until he gets a match to what he heard. It is of interest that even a baby’s babble goes with the phonemes and thus the language of the household.

Children with difficulty in identifying the right phonemes have difficulty with language and reading.

LEARNING TO READ

When I am reading this article, I see only a few words at a time, often no more than two or three.

How does our brain process these words and make sense of what the words mean? Our brain extracts information that comes from the eyes and processes the image.

The part of the brain that extracts information from the image is able to identify shapes.

It is these shape recognition systems, which are present in animals and humans, that we use for recognising the visual identification of words and symbols.

Whenever we read and in whatever language, brain networks are activated. Imaging studies have shown a region in the base of the back of the left side of the brain as the location for recognition of words sense.

This part of the brain recognises symbols and words and when that area is damaged, for example, by a stroke, the person cannot read words. Children who are poor readers do not activate this region of the brain to the same extent as good readers do.

Among illiterates, this region of the brain is activated by objects and faces, unlike literates where activation is more by words.

In other words, reading took over a brain function that was previously related to facial recognition.

When we are born, our brain does not discriminate between left and right mirror images. There is no need to visualise real objects at birth.

However, for reading, we have to discriminate between letters such as b and d or between p and q. Illiterate individuals cannot do so.

We know this phenomenon in the primate world, where we can show that the brain signal elicited by a shape is also elicited by its mirror image.

In literate humans when a word and its mirror word are shown, they are seen as separate and the brain signals are also different.

So in acquiring literacy, we acquire the ability to discriminate between mirror images of letters and words. This again involves the same region of the brain.

Acquiring the ability to read therefore changes the brain.

Reading activates the same language circuits that spoken language does. Thus, learning and reading a language are intimately related.

COMMON CAUSE OF DYSLEXIA

So given the complex process, it is no surprise that some children have difficulty reading.

In a language such as English, the written representation and the phoneme can vary and only recognising the phoneme may not be enough. The sound has to be linked to a string of letters. This is complex.

We can tell from the difficulty that voice recognition programs have in converting speech to text. For English-language speakers, difficulty in recognising the phoneme and converting it to text appears to be the most common reason for dyslexia.

Dyslexia is not an uncommon problem. If a child has difficulty with reading or writing, he or she should be evaluated to see what the reason is. Careful evaluation coupled with the right treatment that could include phonics programs will help.

Today, imaging studies and careful assessment are used to understand dyslexia. The data with dyslexia in Mandarin is complicated.

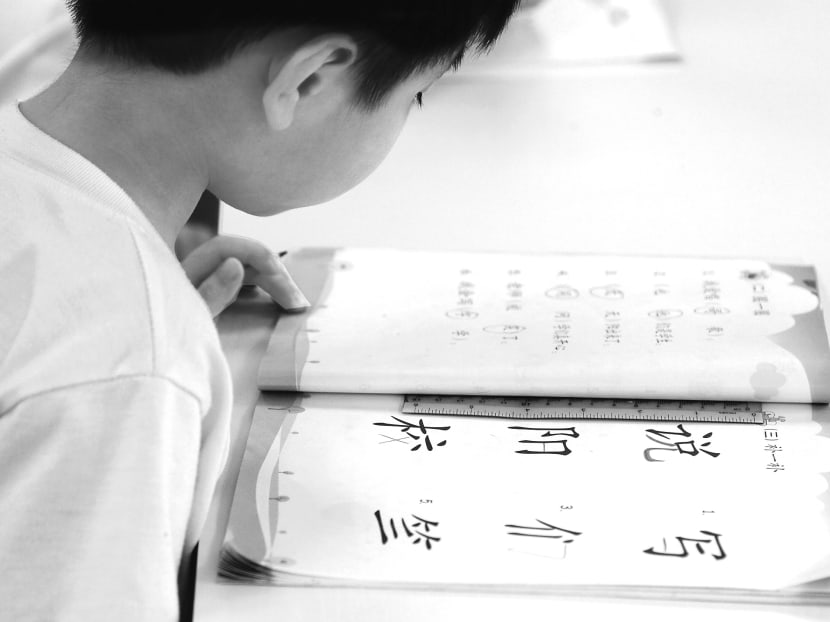

In Mandarin, the individual characters are linked directly to the word or syllable and not to the phoneme. This has led to the suggestion that dyslexia in Mandarin could be due not only to phonological problems, but also minor visual deficits. Unfortunately, studies in languages other than English are very limited.

In the United States, some states have enacted legislation that provides for early identification and treatment. In addition, there are many places that allow accommodation for these children with regard to homework, tests, etc. Allowing extra time for exams is something to consider.

A consistent approach to help accommodate the needs of these children can be very effective. Often, a little extra time for tests can go a long way. The story of Dr Toby Cosgrove is illustrative.

Dr Toby Cosgrove, currently head of the Cleveland Clinic, said because of his dyslexia, he did not do well in his Medical College Admission Test and was rejected by 10 of 11 schools. One admitted him because it saw his creative potential.

Today, he is a leading surgeon, innovator and now a visionary leader in academic medicine.

How many Cosgroves are lost because we do not recognise the problem?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Prof K Ranga Krishnan is dean of the Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore. A clinician-scientist and psychiatrist, he chaired the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences at Duke University Medical Centre from 1998 to 2009.