With monthly fees up to S$3,000, why do some parents send kids to private preschools?

SINGAPORE — On an average week in school, five-year-old Jacob could be found on campus making donuts, learning the recorder, or honing his acting chops in drama class. Soon, he will even learn how to play the violin.

Children at an outdoor playground at Maple Bear preschool at Mediapolis on Sept 7, 2023.

- After Kinderland made headlines for cases of child mismanagement, some parents are questioning just how different a child’s experience is at pricier, private preschools, compared to government-funded schools

- While enrolling a child into a kindergarten programme in government-supported preschools costs around S$160 a month, fees at schools run by private operators can reach S$3,000

- Parents said that extra-curricular activities included in some private schools' curriculum free up time for them to spend with their children, with smaller teacher-to-student ratios also a big draw

- Early childhood professionals said the differences between government-supported and private preschools are not as clear as before due to an increase in government funding and regulatory improvements in the sector

SINGAPORE — On an average week in school, five-year-old Jacob could be found on campus making donuts, learning the recorder, or honing his acting chops in drama class. Soon, he will even learn how to play the violin.

This exposure to myriad extra-curricular activities is one of the main reasons Mr Sebastian Goh, 34, enrolled his son in a private preschool in Farrer Park — even though it sets him back about S$1,800 every month after subsidies.

“It's like an interest check,” said Mr Goh, who works in insurance as a corporate trainer.

“We are giving him the master checklist, so he can kind of see everything. If he likes something then he can pursue it, but if he doesn't, then so be it. It's like a starter course for everything, that's how I see it.”

Safety measures in preschools have been on Singaporeans’ minds in recent weeks after two Kinderland outlets made headlines for cases of child mismanagement.

With Kinderland charging fees as high as S$1,794 for its childcare and kindergarten programmes, some parents are questioning just how different a child’s experience is at pricier, private preschools — as opposed to those that receive funding from the Government.

In Singapore, most children attend a two-year kindergarten programme in preparation for their admission into primary school, and subsidies by the Government keep fees generally affordable for parents.

For children who are Singapore citizens aged five to six, the preschool participation rate is 97 per cent in 2022, according to the Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA).

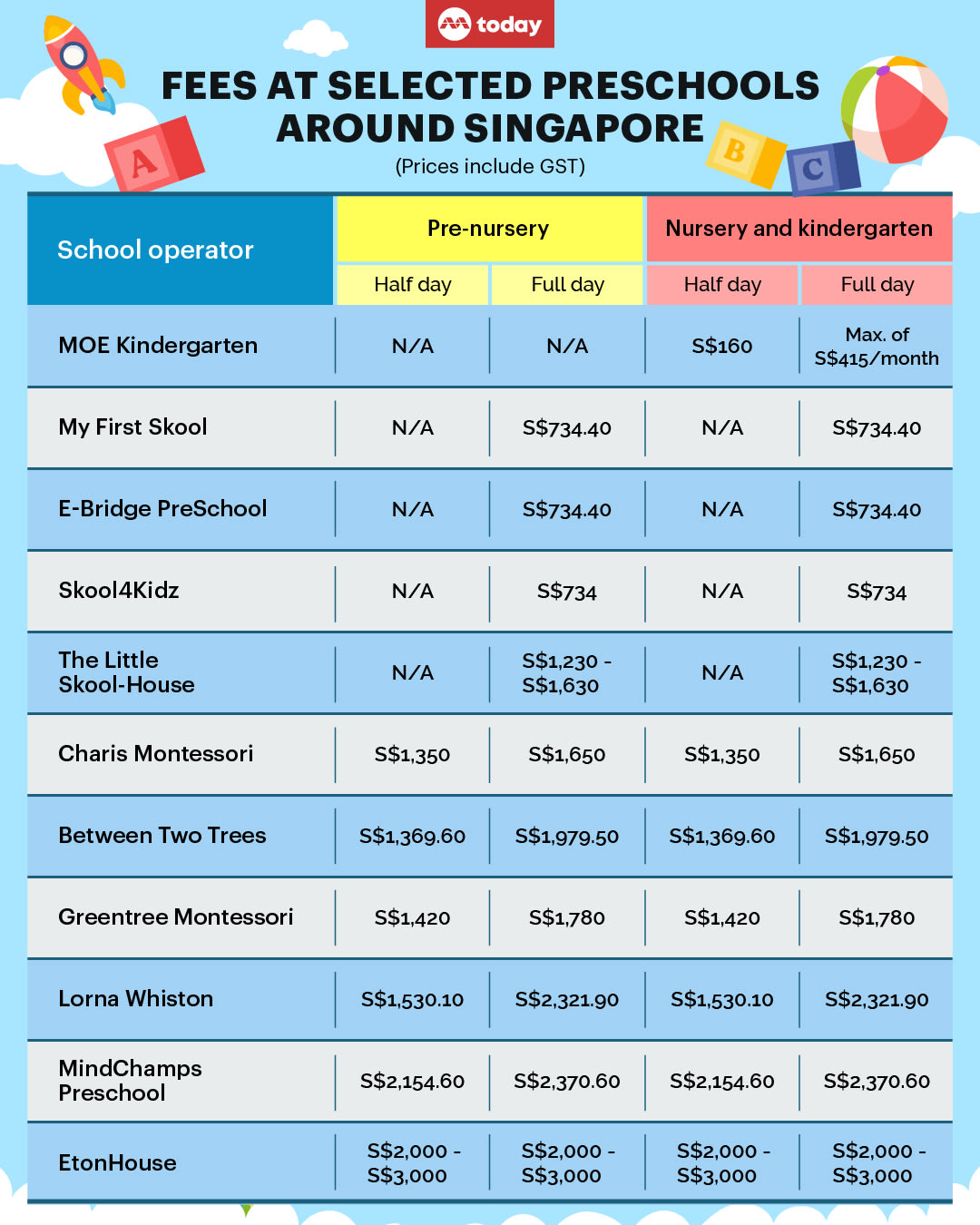

However, while enrolling a child into a kindergarten programme in government-supported preschools costs around S$160 a month, monthly fees at schools run by private operators like the one Jacob attends can go up to S$3,000.

For children under five years old in pre-nursery or nursery programmes in government-supported preschools, the monthly school fees can be slightly higher at S$734 — although that figure is usually brought down to around S$300 after subsidies.

This stark difference in price begs several questions. Why do parents choose to enrol their children in significantly more expensive preschools, and what are the key differences between them?

THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF PRESCHOOLS IN SINGAPORE

Preschools in Singapore can generally be classified into two categories: Schools that are funded by the Government, or “government-supported” preschools, and those that are not — which are run by private operators.

MOE kindergartens fall in the first category alongside a list of privately owned schools appointed on government schemes, known as anchor operators and partner operators.

The Anchor Operator Scheme, which started in 2009, provides funding to five selected preschool operators to increase access to good quality and affordable early childhood care and education, especially for children from lower income backgrounds.

They are PCF Sparkletots Preschool, My First Skool, My World Preschool, Skool4Kidz and E-Bridge Pre-School.

The suitability of operators and centres under these schemes is assessed by the ECDA on multiple factors such as track record, financial sustainability, accessibility of centres and local preschool demand.

The monthly fees at anchor operators for full-day child care, full-day infant care and kindergarten are capped at S$680, S$1,235 and S$150 respectively, excluding goods and services tax.

For the 331 centres under the Partner Operator Scheme, the fees are capped at S$720 for full-day child care and S$1,290 for infant care, but do not cover kindergarten programmes.

According to an ECDA spokesperson, more than 60 per cent of preschoolers are currently enrolled in either MOE kindergartens, or preschools run by anchor operators or partner operators.

The rest of the preschoolers are enrolled in private preschools which do not fall under the anchor or partner operator schemes, where fees can go up to S$3,000 a month.

‘ALL-IN-ONE’ CURRICULUM FREES UP EXTRA TIME FOR THE WEEKENDS

When TODAY asked parents who enrolled their children in more expensive private preschools why they did so, most mentioned the fact that their school of choice offers various extra-curricular activities during school hours.

For Mr Goh, the father of five-year-old Jacob, such an arrangement allows his family to spend more time together on the weekends as opposed to spending that time to send their son to other enrichment classes.

Jacob initially attended a government-supported preschool near his home in Telok Blangah.

“The thing that really attracted me is compacting things that we will do on a weekend. Enrichment classes, English reading classes, all that is now within the school curriculum time,” said Mr Goh.

“So on weekends we can go and play, we can go and explore other things. Go to the park, go to places that he usually wouldn't get a chance to go to during school.”

Other parents TODAY spoke to, like 40-year-old teacher Sandra Lim, agreed that having extra time to spend with their children on the weekends was the main draw for their decision, despite having to pay a premium.

Her son, who is two-and-a-half years old, attends the MindChamps playgroup programme at its Midview City outlet.

“We don’t have to go and find out what else is available. They have already planned everything out in their curriculum… so in a way it’s very convenient,” Ms Lim said.

SMALLER CLASS SIZES

Another oft-mentioned reason is the benefits of having a smaller class size.

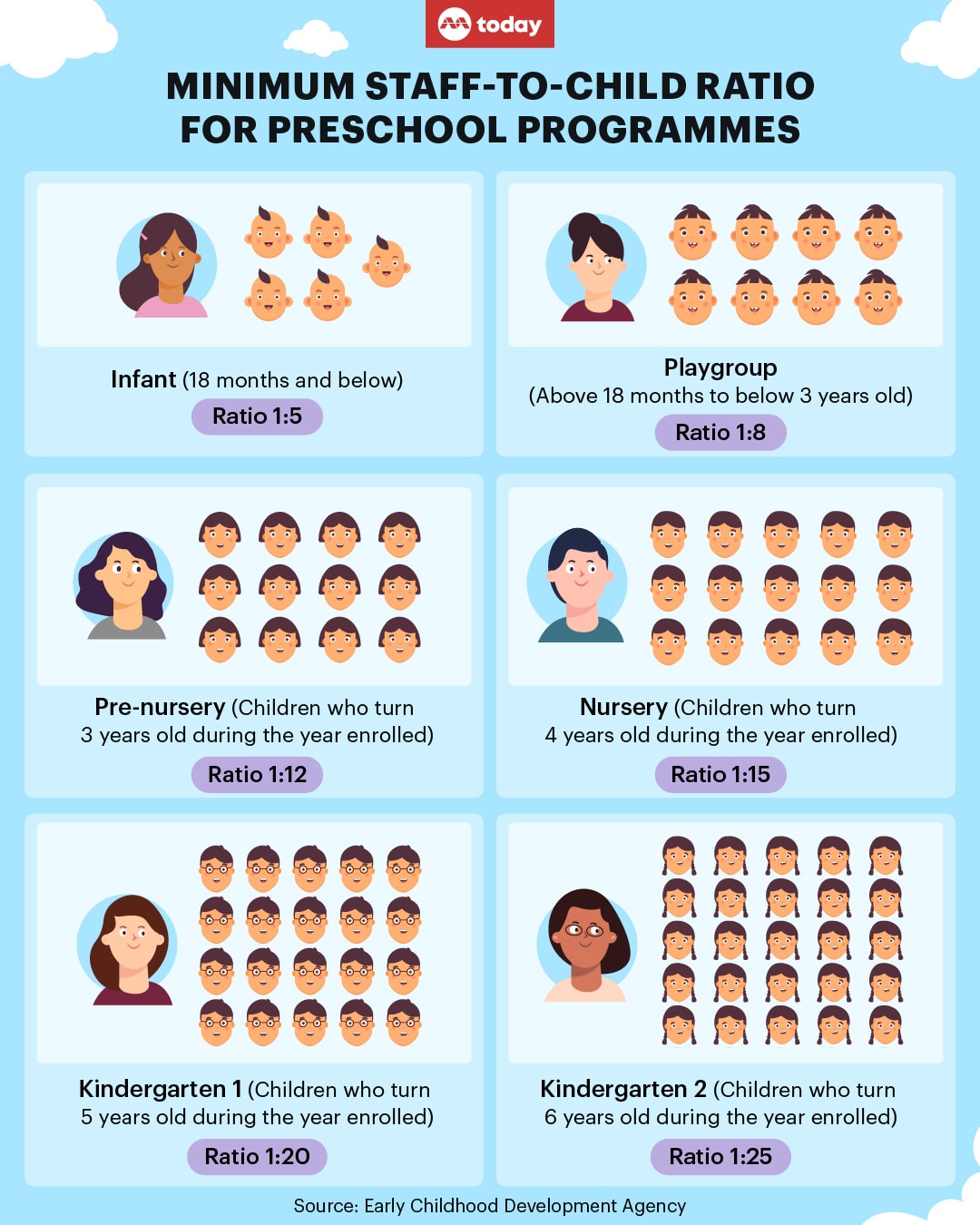

While ECDA stipulates mandatory staff-to-child ratios for different class levels within preschools, some private operators take it a step further.

For instance, private preschool operator MapleBear implements a strict 1:10 staff-to-child ratio for its kindergarten programme, whereas ECDA mandates a 1:20 ratio for kindergarten 1, and 1:25 for kindergarten 2 classes.

Ms Carol Loo, whose nine-year-old daughter used to attend a private preschool in Seletar, said that a smaller teacher-to-child ratio allows educators to give better feedback to parents as their attention would not be spread too wide between students.

Parents said that class ratios have safety implications, too.

Teachers would be better able to spot oddities in behaviour or signs of injuries and update parents more periodically, said Ms Loo, a 42-year-old financial services consultant.

“The attention to detail matters a lot. It makes you feel assured that they are keeping a look out for the kids,” she said.

Ms Dawn Lin, whose three-year-old son attends the playgroup programme at MapleBear’s one-north franchise, added that there is a health and hygiene benefit to having smaller class sizes, too, as it is less likely for viruses to spread.

The 40-year-old who works in trading operations also believes that the focused attention provided in private schools will help her child academically.

“In the playgroup, you can see the difference in how many words they pick up, they can count their numbers, recite the alphabets, everything,” she said.

Parents are also attracted by the "play-and-learn" approach adopted by private preschools, as they do not want to stress their children too much at a younger age.

But how different are these preschools exactly — and do these differences justify parents’ reasons for choosing pricier options?

HOW DIFFERENT ARE GOVT-SUPPORTED AND PRIVATE PRESCHOOLS?

While there is a belief that private preschools provide services that are comparatively more “premium”, experienced educators in the industry said that the definitive differences between both are not as straightforward in recent years due to an increase in government funding and regulatory standards.

Extra-curricular activities like cooking and instrument-playing, larger compounds, and a curriculum built upon a play-based philosophy may be par for the course for certain private operators, but these features can increasingly be found at government-supported schools too.

My First Skool (MFS), an anchor operator under the social enterprise NTUC First Campus, told TODAY that an integral part of its curriculum involves outdoor play and learning through “engaging and enriching” activities — using learning zones to recreate zoos, outdoor camp sites and bakeries within the centre.

With additional government funding, more up-and-coming anchor operators such as those situated in larger compounds have “inviting and stimulating” physical and outdoor environments for children, said Ms Melissa Goh-Karssen, an ECDA fellow and senior lecturer for the early childhood education programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS).

Anchor operators may also offer optional extra-curricular activities on weekdays outside of curriculum hours.

For instance, a spokesperson from E-Bridge Pre-School said that the school offers speech and drama, abacus and coding classes, to name a few.

For these reasons, several parents who chose anchor-operators for their children told TODAY that they do not feel as though they are “missing out”.

“The structure is there, our confidence is there,” said Mr Ang Ye Xiang, a 35-year-old operations manager who enrolled his five-year-old son into an MFS branch in Ang Mo Kio.

“We don't feel our children receive less or are inferior if they were to attend a government-supported school.”

Nevertheless, there still exists a sentiment among some parents that the curricula offered by private operators are more comprehensive.

Ms Adeline Tan spends about S$1,900 a month on her six-year-old daughter’s school fees at Lorna Whiston, a private preschool.

The 42-year-old finance advisor said that the centre’s niche on speech and drama was enticing as it would equip her daughter with crucial presentation skills before entering primary school.

Ms Tan was particularly impressed by the centre’s tradition of having its kindergarten students give their graduation speech on stage in front of parents, teachers and fellow peers.

“If that is something we can train, then why not actually do it?” she said.

WHAT DO STUDENTS REALLY NEED TO KNOW WHEN THEY ENTER PRIMARY 1?

When TODAY asked the Ministry of Education (MOE) what specific knowledge or skills a child would be required to have prior to entering primary school, the ministry said that the academic expectations for children entering Primary 1 are “basic”.

Children should be able to express their needs and wants, follow simple instructions and recognise letters of the alphabet, for instance. Numeracy-wise, children should be able to recite numbers 1 to 10 in sequence and recognise them in numerals and words, among other simple tasks.

Aside from having such knowledge, MOE said that “it is more crucial for children to have good social and emotional skills and the joy of learning”.

“The reality of it is that the whole social-emotional part is of utmost importance,” said Ms Goh-Karssen of SUSS.

“When they're in primary school, the biggest thing they need to deal with in their transition is change, because the preschool and primary school environments are very different.”

She emphasised the need for children to be self-sufficient in several “physical” aspects to ensure a smoother transition.

For example, students would need to be able to clean up after themselves in toilets, make decisions on what to eat during recess and carry trays of food afterward.

Bullying in school is another scenario children should be prepared for, she said, adding that social-emotional skills go hand-in-hand with being able to articulate themselves.

“Your child needs to be able to know how to feel confident and walk away from such situations, or know how to reach out and talk about it for help,” she said.

Ultimately, Ms Goh-Karssen said that the choice of preschool very much depends on whether a child is suited to the centre’s teaching approach.

“If your child is not a child that takes to that teaching approach, you can put your child in that setting, but it may not do your child justice,” she said.

“You could put two of your same kids in the best schools — one may make it, one may not. Because the other determining factor is your child itself. Children are all different.”