Sweeping laws proposed to arm Govt with powers to fight fake news

SINGAPORE — After two years spent studying the threat of fake news, Singapore is taking things a step further with the introduction of sweeping new laws that will, among other things, give government ministers broad powers to quickly stop the dissemination of online falsehoods and punish those who create and spread them.

SINGAPORE — After two years spent studying the threat of fake news, Singapore is taking things a step further with the introduction of sweeping new laws that will, among other things, give government ministers broad powers to quickly stop the dissemination of online falsehoods and punish those who create and spread them.

These new laws, which will come under a new Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill, were tabled in Parliament on Monday (April 1).

The proposed new laws come after a parliamentary committee was set up to study the issue of deliberate online falsehoods and make recommendations on how to fight the scourge.

The committee, which put out its report last September, recommended introducing laws that will, among other things, give regulators the powers to compel Internet platforms to stop the distribution of falsehoods by their users and cut off money flows to the creators of fake news.

Singapore’s moves are in line with global trends.

Countries such as France have also taken steps to enact laws against fake news, while Australia plans to do so soon.

Over the weekend, Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg called on governments around the world to implement regulations governing the Internet, including rules on hateful and violent content, election integrity, privacy and data portability.

Also on Monday, the Government tabled changes to the Protection from Harassment Act, which include making doxxing a crime and allowing victims of falsehoods to seek recourse from the law. Doxxing is publishing someone’s information online to harass or threaten them or encourage others to commit violence against them.

Legal measures against foreign interference, however, are not covered under the new piece of legislation. But TODAY understands that separate laws will be tabled at a later date to deal with the threat.

NEW MINISTERIAL POWERS

The 77-page Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill gives all government ministers the power to issue a variety of orders, such as directing online news sites to publish corrections to falsehoods.

In extreme cases, they will be able to order the publisher to take down an article or order Internet service providers to disable user access to errant sites.

Government ministers will also be able to order that the revenue streams of errant online news sites be cut off, by prohibiting them from soliciting revenue as well as barring companies from advertising on such platforms.

They will be able to direct tech companies such as Facebook and Twitter to disable fake social media accounts, including those that use bots to amplify falsehoods.

Ministers will also be able to issue general correction orders. That is, if a false statement has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the victim’s reputation, a third party such as the mainstream media can be ordered to publish a correction, to draw the public’s attention to the falsity of the statement or to a corrected statement.

CRIMINAL SANCTIONS

The new laws on fake news will not target individuals who innocently share a fake news post or article. In short, they will not be prosecuted.

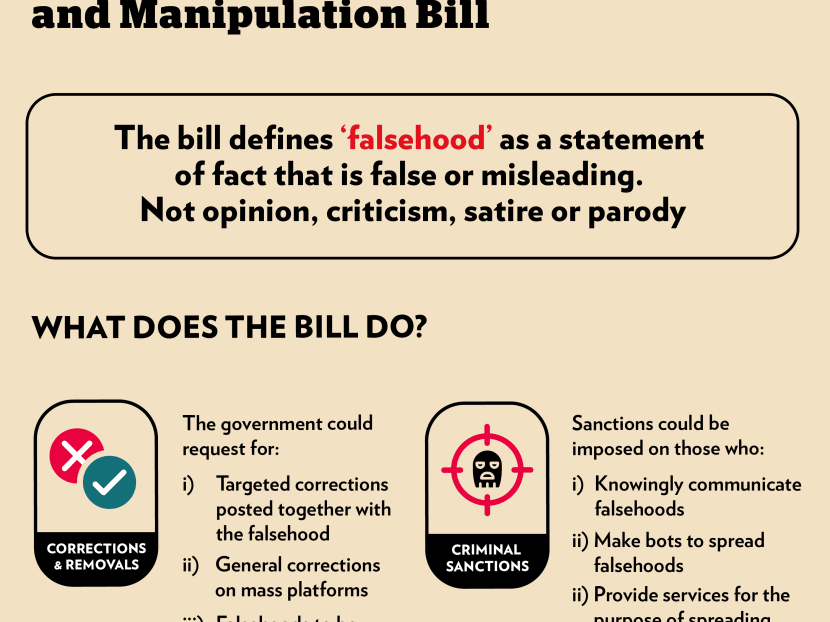

Requiring online news sources to publish corrections alongside the falsehoods will be the primary response.

However, “malicious actors” who deliberately use falsehoods to undermine public interest may be charged with criminal offences. They can be fined and/or jailed.

Such offences include making false statements, programming bots to quickly circulate fake news, or not complying with orders issued by government ministers.

For instance, individuals guilty of making online falsehoods face a fine of up to S$50,000 or a maximum five-year jail term, or both.

On the higher-end of the spectrum, organisations that do not comply, say, in removing fake accounts that use bots to spread falsehoods, could face a maximum fine of up to S$1 million.

In the event that falsehoods are discovered during an election period, where the Government would have been dissolved, the “alternate authority” who can issue such orders will be a public officer appointed by a minister before the writ of election is issued.

An alternate authority cannot be appointed during the election period.

DEFINITIONS OF FALSEHOOD AND PUBLIC INTEREST

Given the concerns that the sweeping new laws might stifle free speech, the Ministry of Law (MinLaw) stressed in a statement on Monday that the Bill “targets falsehoods", not opinions and criticisms.

“The Bill defines a falsehood as a statement of fact that is false or misleading. It does not cover opinions, criticisms, satire or parody,” it added.

Ministers can only issue orders subject to the fact that the statements are falsehoods and that the orders are in the public’s interest.

The legislation spells out the meaning of public interest, which covers six areas: Orders can be issued in the interest of the security of Singapore or any part of Singapore, to protect public health or public finances, or to secure public safety or public tranquillity as well as in the interest of the friendly relations between Singapore and other countries.

Other areas of public interest include:

To prevent any influence of the outcome of a presidential or general elections as well as by-elections or a referendum.

To prevent incitement of feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will among different groups of persons.

To prevent a weakening of public confidence in the Government, an organ of state or a statutory board and their roles in carrying out their duties or functions or in exercising their powers.

SAFEGUARDS IN PLACE

In making its recommendations, the 10-member Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods also stressed the need for safeguards, to ensure due process and the proper exercise of power, given concerns raised during the committee’s public hearings that new laws could be used to stifle free speech.

The new laws tabled on Monday include judicial oversight — the courts have a final say in determining whether a statement made is a falsehood.

Still, government ministers can take action in the time it takes to file a court application to quickly prevent the falsehood from spreading.

Those accused of peddling falsehoods have the right of appeal to the High Court, but they bear the burden of proving that the statements made are not falsehoods. Such a principle can already be found in existing defamation laws, which is to discourage people from putting out a falsehood and turning around to say that it is for others to prove it is false.

Similarly, Internet service providers and Internet intermediaries such as Facebook and Twitter can also make appeals to the High Court if they are found guilty of not complying with the rules.

However, an appeal can only be made after the individual or organisation has gone to the government minister to cancel the order but the minister refused to do so.

FAKE NEWS LAWS ELSEWHERE

Singapore’s new laws may perhaps be the most comprehensive yet in the global war against fake news, although other countries have made moves in the same direction.

Governments around the world have been left increasingly frustrated with the lack of action by tech giants such as Facebook and Twitter to clamp down on fake news, peddled by local and foreign-state actors to stir social unrest and interfere in foreign elections.

Several countries are looking to push out their own laws to crack down on the malicious use of online media and social media platforms.

In the aftermath of the mosque shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand, the Australian government has announced plans to introduce laws this week that would prevent social media platforms from being “weaponised” to live-stream violent crimes.

Some countries such as France already have laws countering fake news. Last October, the French Parliament passed two laws to prevent the spread of falsehoods during election campaigns, in response to allegations of Russian interference in the country’s presidential election in 2017.

The country’s new laws allow a candidate or political party to seek a court injunction against the publication of falsehoods during the three months leading up to a national election and also targets fake news bots.

Perpetrators could face a year in prison and a fine of €75,000 (about S$114,000).