The Big Read: Opposition’s star dims after death of Nik Aziz

The funeral of Nik Aziz,the spiritual leader of Malaysian opposition PAS, held at Tok Guru Mosque in Pulau Melaka, Kelantan. Photo: The Malaysian Insider

SINGAPORE — Nik Aziz Nik Mat, the spiritual leader of the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), who died from prostate cancer at his home on Thursday night, is perhaps among the most important religio-political figures in Malaysia since the 1970s.

He played a pivotal role in the transformation of the PAS to its current ideological form, changing an organisation once described as a village party to the second-largest one in the country, appealing not only to Muslims, but also to many non-Muslims.

While he was known for his conservative Islamic stance, he was practical enough to understand that the PAS had to work in a coalition of multi-ethnic parties to form a government. He was also a strong champion of its decision to join the three-party opposition coalition, Pakatan Rakyat.

For many Malaysians, he was an exception to the political norm: A corruption-free figure who pushed for accountable governance and adopted a colour-blind approach to politics while leading a humble lifestyle.

Following his death, Ms Nurul Izzah Anwar, daughter of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, posted a Facebook message that said: “The passing of a beloved ulama (religious cleric) ... The jailing of (a) people’s warrior.”

Indeed, his death could not have occurred at a worse time for the Malaysian opposition, coming as it did only two days after the tremor that was the imprisonment of Anwar for sodomy.

While Anwar’s jailing leaves the opposition without a clear leader, the death of Nik Aziz will have just as big an impact. It is likely to accentuate the political divide in the PAS, weaken Pakatan Rakyat and alter the political landscape of Malaysia. That is a result of the crucial role Nik Aziz played in Malaysia’s opposition politics — that of an important arbitrator for the different factions in the PAS, as well as a reasonable and pragmatic leader respected by all PR leaders. His death is likely to weaken both the PAS and PR, and provide the right political opportunity for the governing Barisan Nasional coalition to consolidate its political power.

Nik Aziz received his earliest education in pondok (Islamic boarding) schools in the northern Malaysian states of Kelantan and Terengganu. These schools are known for their traditionalist approach to Islam, which is heavily influenced by Sufism (a spiritual variant of Islam). His traditionalist background did not, however, prevent him from furthering his studies at the Darul Uloom Deoband in Uttar Pradesh, India, an institution known for its more modernist variant of Islam. In 1957, Nik Aziz proceeded to the University of Punjab in Lahore, Pakistan, to study Quranic exegesis and subsequently to Egypt, where he pursued a study of Islamic religious jurisprudence at the prestigious Al-Azhar University in Cairo.

He eventually developed his own approach to political Islam, which combined the ideas of groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Jamaat-e-Islami with the local Islamic context of Malaysia.

Upon his return to Malaysia, he began his career as a religious preacher. He joined the PAS in 1967 and contested a by-election that secured him the parliamentary seat of Kelantan Hilir (currently Pengkalan Chepa). He held this seat until 1986, when a party decision was made for him to contest the state seat in Chempaka. In 1990, following the PAS’ historic victory in Kelantan, he was appointed Chief Minister of the state and remained in the position for more than two decades.

One of the first initiatives he proposed upon joining the PAS was to institutionalise a tarbiyah (the education and guidance of members) system, which he borrowed from the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

Similar to those of the Leninist parties, this system involved dividing members into smaller cells known as usrah, which were led and nurtured by a party leader. This ensured party members not only understood the objectives and mission of the party, but developed a sense of loyalty to it as well. The fact that PAS activities and events are run completely by party members on a voluntary basis is testimony to the success of this system. Despite his long career in the PAS, it was only in 1982 that he began shaping the future direction of the party in a significant way.

As a key figure of the younger ulama faction within the PAS, he was responsible for deposing the party’s then-president, Asri Muda. Together with senior members of the PAS such as former spiritual leader Yusuf Rawa and current president Abdul Hadi Awang, he institutionalised a shift in its ideological position, moving it from a hard-line Malay nationalist party to an Islamist one.

In line with this ideological shift, a new leadership structure modelled after the Iranian velayat-e-faqih (rule of the jurists) was introduced. The concept of “kepimpinan ulama” (leadership of the religious scholars) became an important aspect of the PAS’ politics. Nik Aziz also established as a cornerstone of the PAS’ objectives the promulgation of an Islamic state and implementation of Islamic laws (including hudud laws), firmly placing the party within the league of Islamist parties worldwide seeking the same objective.

Together with other leaders, he clearly recognised the need for the PAS to expand its political base

beyond northern Malaysia. In an interview I conducted in 2009, he noted that the key weakness of the Jamaat-e-Islami is its elitist-style politics, which limited the party’s traction within the elite of Pakistani society. Similarly, he noted that the PAS was viewed as a “kampung” (village) party and its membership was thus limited to religious scholars and villagers.

To counter this image, Nik Aziz and Fadhil Noor, the late party president, formulated a strategy in 1990 to reach out to professionals in Malaysian society. Several key leaders of the PAS, including Mr Husam Musa and Dr Hatta Ramli, were recruited as a result of this outreach. However, it was not until 1998, following the sacking of Anwar Ibrahim as Deputy Prime Minister, that the party saw an influx of professionals, many of whom were upset by the government’s policies.

This led to the ulama-professional partnership, which is now an important pillar of the party.

Nik Aziz understood the importance of contextualising his thoughts within the Malaysian religio-political context. An example is the introduction of the Islamic political concept of “tahaluf siyasi” (cooperation with non-Muslims for a common political objective) that it introduced to allow it to work with the Democratic Action Party (DAP), which does not support its Islamist agenda. Realising that it was close to impossible for the PAS to capture state power on its own, he sought to build a closer working relationship with the DAP and other political parties, including the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR).

As Chief Minister, he sought to transcend ethnic difference by building bridges with the Chinese and Indian communities in Kelantan. Once, during the holy month of Ramadan, he invited an imam (prayer leader) from China to lead prayers at the Kota Baru city hall to show that Islam was a universal religion which rose above racial differences. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, he was seen as the bedrock of the PAS’ power in Kelantan and the key factor for its continued hold on power in the state.

However, since the 2008 general election, the PAS has been marred by the worst internal conflict in years between its two key factions — the more conservative ulama wing and the more reformist professionals, sometimes referred to as the “Anwarites” due to their close relationship with Anwar. Nik Aziz has been erroneously portrayed by some analysts as the defender of the PAS’ reformist faction. While he believes in the need for partnership between the ulama and professionals, his own views on issues such as the implementation of hudud in Kelantan place him firmly within the conservative camp. He was steadfast in his defence of the PAS’ right to implement hudud in Kelantan, a key issue of dispute between the party’s two factions, but his esteemed position saw members of both factions being more willing to support his ideas and to allow him to arbitrate differences between them.

With his death, the PAS has lost an important arbitrator between the two contending factions. The “Anwarites” are now at an added disadvantage: The pivotal post of spiritual leader of the party is likely to be filled by Dr Harun Din, the current deputy spiritual leader, who is known for his hard-line stance and support for the ulama wing. This is likely to exacerbate the fissures between the two factions and could potentially trigger an outright break between them.

The next PAS annual meeting scheduled for June will probably see a huge clash between the two factions and perhaps determine the future direction of the party. Perhaps most importantly, the PAS has lost one of the key reasons for its continued success in Kelantan. With the death of Nik Aziz and the absence of any PAS leaders of his aura and stature, the party is likely to face an uphill task in defending the state. The performance of the PAS candidate in the state seat of Chempaka in the coming by-election — which must be called following Nik Aziz’s death — will be a gauge of the actual level of support it enjoys in the post-Nik Aziz era.

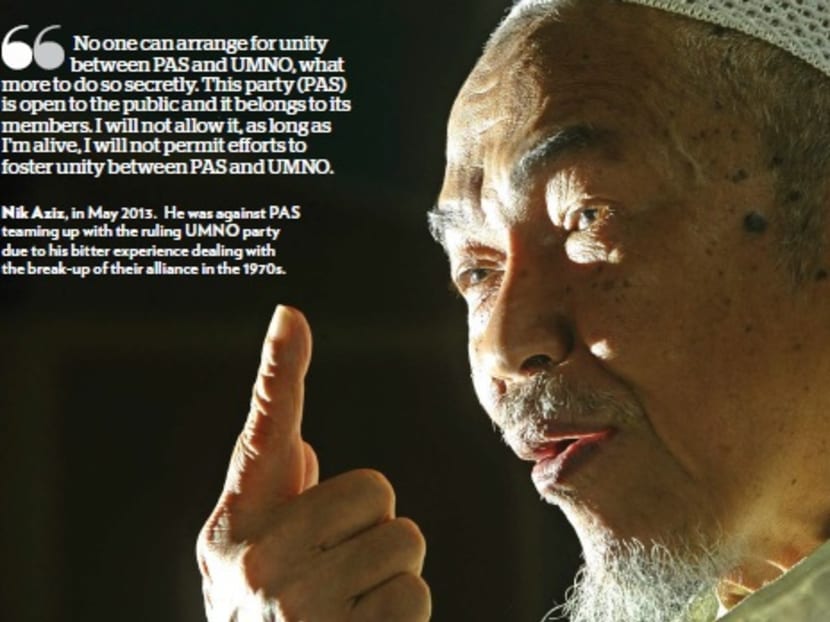

It has been argued that Nik Aziz has been instrumental in ensuring that the PAS remains within the ambit of the PR and that one of the key consequences of his death would be the break-up of the opposition coalition. There is little doubt Nik Aziz was dead-set against an alliance between the PAS and the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), which is headed by Prime Minister Najib Razak.

Nik Aziz’s bitter, first-hand experience in dealing with the fallout between UMNO and PAS in the 1970s has kept his party from venturing into another alliance with UMNO.

However, there is also little evidence to show he wanted the PAS to remain in the PR under any circumstances. He refused to concede ground to the DAP over the PAS’ objective to promulgate an Islamic state, leading to the demise of the Barisan Alternatif coalition in 2001. The situation, therefore, is still murky and the jury on the question of whether his death would be a major factor leading to the bifurcation of the PR is still out.

For UMNO, however, his death might give rise to an important political opportunity. The absence of a leader of Nik Aziz’s gravitas and charisma is likely to weaken the PAS, especially in the state of Kelantan. Combined with a lack of economic development, this could cause Kelantanese to re-assess the party through a different lens.

UMNO leaders will now intensify the pressure on the PAS to form a united Malay-Muslim alliance, though the PAS will probably remain outside the fold of the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition because a vast majority of its members oppose such a move. Nevertheless, this courting process might be enough to prompt the PAS to leave the PR.

The grim situation facing the opposition alliance is best summed up by a tweet posted by PKR’s deputy youth chief, Dr Afif Bahardin, after news broke of Nik Aziz’s death of Thursday night. “Tuan Guru Nik Abdul Aziz is gone forever. Two big miseries this week,” he wrote.

The opposition will find it hard to replace Anwar. But filling the shoes of Nik Aziz is perhaps an impossible task.

Taken together, the loss of its twin pillars makes the prospect of a united, cohesive Pakatan Rakyat assuming power in Putrajaya increasingly dim.