Coronavirus could attack immune system like HIV by targeting protective cells, warn scientists

HONG KONG — The coronavirus that causes Covid-19 could kill the powerful immune cells that are supposed to kill the virus instead, scientists have warned.

HONG KONG — The coronavirus that causes Covid-19 could kill the powerful immune cells that are supposed to kill the virus instead, scientists have warned.

The surprise discovery, made by a team of researchers from Shanghai and New York, coincided with frontline doctors' observation that Covid-19 could attack the human immune system and cause damages similar to that found in HIV patients.

Researchers Lu Lu, from Fudan University in Shanghai, and Jang Shibo, from the New York Blood Centre, joined the living virus, which is officially known as Sars-CoV-2, on laboratory-grown T lymphocyte cell lines.

T lymphocytes, also known as T cells, play a central role in identifying and eliminating alien invaders in the body.

They do this by capturing a cell infected by a virus, bore a hole in its membrane and inject toxic chemicals into the cell. These chemicals then kill both the virus and infected cell and tear them to pieces.

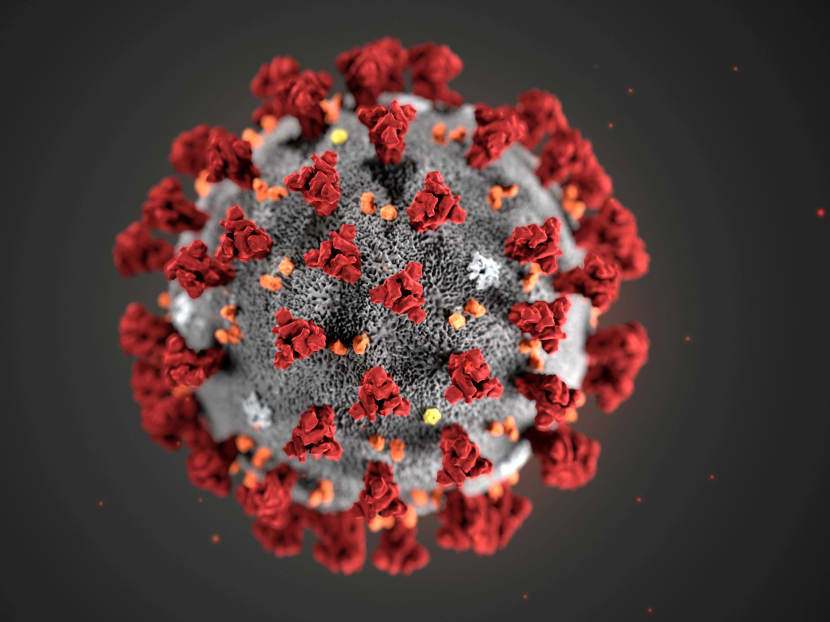

To the surprise of the scientists, the T cell became a prey to the coronavirus in their experiment. They found a unique structure in the virus's spike protein that appeared to have triggered the fusion of a viral envelope and cell membrane when they came into contact.

The virus's genes then entered the T cell and took it hostage, disabling its function of protecting humans.

The researchers did the same experiment with severe acute respiratory syndrome, or Sars, another coronavirus, and found that the Sars virus did not have the ability to infect T cells.

The reason, they suspected, was the lack of a membrane fusion function. Sars, which killed hundreds in a 2003 outbreak, can only infect cells carrying a specific receptor protein known as ACE2, and this protein has an extremely low presence in T cells.

Further investigations to the coronavirus infection on primary T cells would evoke "new ideas about pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic interventions," the researchers said in a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Cellular & Molecular Immunology this week.

A doctor, who works in a public hospital treating Covid-19 patients in Beijing, said the discovery added another piece of evidence to a growing concern in medical circles that the coronavirus could sometimes behave like some of the most notorious viruses that directly attack the human immune system.

"More and more people compare it to HIV," said the doctor who requested not to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue.

In February, Mr Chen Yongwen and his colleagues at the PLA's Institute of Immunology released a clinical report warning that the number of T cells could drop significantly in Covid-19 patients, especially when they were elderly or required treatment in intensive care units. The lower the T cell count, the higher the risk of death.

This observation was later confirmed by autopsy examinations on more than 20 patients, whose immune systems were almost completely destroyed, according to mainland media reports.

Doctors who had seen the bodies said the damage to the internal organs was similar to a combination of Sars and Aids.

The gene behind the fusion function in Sars-CoV-2 was not found in other coronaviruses in human or animals.

But some deadly human viruses such as Aids and Ebola have similar sequences, prompting speculation that the novel coronavirus might have been spreading quietly in human societies for a long time before causing this pandemic.

But there was one major difference between Sars-CoV-2 and HIV, according to the new study.

HIV can replicate in the T cells and turn them into factories to generate more copies to infect other cells.

But researchers Lu and Jiang did not observe any growth of the coronavirus after it entered the T-cells, suggesting that the virus and T-cells might end up dying together.

The study gives rise to some new questions. For instance, the coronavirus can exist for weeks on some patients without causing any symptoms. How it interacted with the T cells in these patients remained unclear.

Some critically ill patients also experienced cytokine storms, where the immune system overreacts and attacks healthy cells.

But why and how the coronavirus triggers that remains poorly understood. SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST