Covid-19 lockdown fears: As a Singaporean living in Beijing, this is what I am going through

As news broke this week that Beijing will start testing nearly all its 21 million residents and workers for Covid-19 to curb an outbreak and avert a lockdown that Shanghai has endured for a month, TODAY approached a Singaporean living in the Chinese capital to share her experience and thoughts. This is the account of Ms Cheang Yit Shan, 35, an advertising executive who has lived and worked in Beijing since 2018.

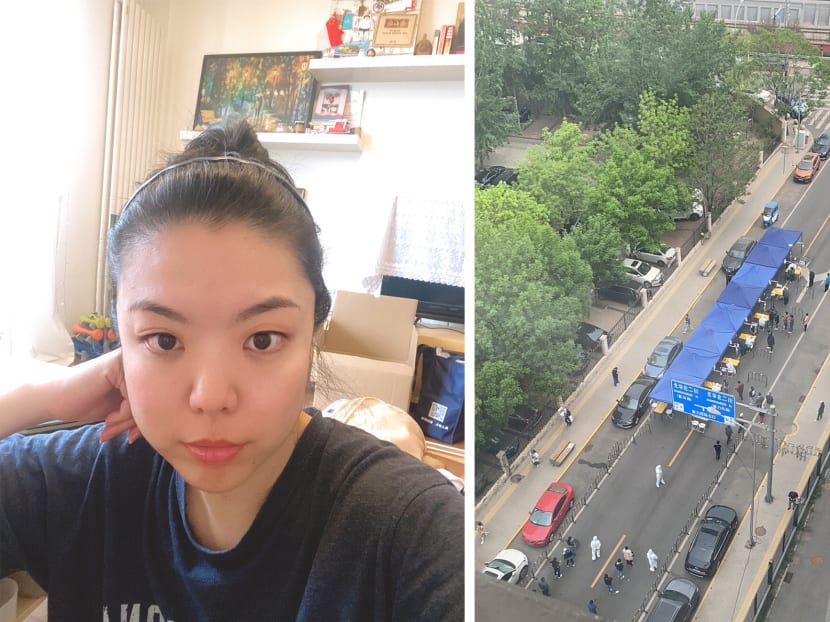

Ms Cheang Yit Shan (left) in her Beijing apartment on April 27, 2022. (Right) The tent set up for Covid-19 testing at her apartment compound.

As news broke this week that Beijing will start testing nearly all its 21 million residents and workers for Covid-19 to curb an outbreak and avert a lockdown that Shanghai has endured for a month, TODAY approached a Singaporean living in the Chinese capital to share her experience and thoughts. This is the account of Ms Cheang Yit Shan, 35, an advertising executive who has lived and worked in Beijing since 2018.

BEIJING — When TODAY called me on Tuesday (April 26) at 5.05pm about writing this piece, I was being rushed out of the office, my third time over the last two years.

Each time, it was because a colleague had come into close contact with a positive Covid-19 case and the office required disinfection.

Each time, life went back to normal after 14 days.

Will it be different this time round?

Last Sunday, Beijing announced that everyone who works and lives in the Beijing district of Chaoyang would have to undergo three nucleic acid tests, the first scheduled for the next morning. Nucleic acid tests are equivalent to Singapore’s polymerase chain reaction or PCR tests.

Chaoyang is the biggest district by size in Beijing, packed with 3.45 million residents, and host to embassies and many offices. I live in Chaoyang and work in a neighbouring district.

It was the first time the government ordered testing on such a scale.

On Monday night, Beijing extended mass testing to 11 districts across Beijing, covering nearly all of its 21 million residents and workers, also a first.

Remote working was recommended while tourist attractions were told to close.

While I pondered what this means, my sister and some friends in Singapore were excitedly preparing for their first overseas holidays in two years after Singapore eased most Covid-19 restrictions.

Colleagues in our Singapore office were looking forward to in-person meetings again.

It felt like a game of musical chairs.

For two years, I had lived much like before Covid-19, going to performances, Christmas parties, after work drinks and travelled to many parts of China.

My friends and family in Singapore had done their time. Is it my turn?

As I left my office on Tuesday, I mentally checked off all the items I had taken with me, as my colleagues joked about their food supplies and plans to work in cafes for the next few days.

Up to maybe a week ago, a report of a neighbourhood in lockdown would not have been any cause for concern.

After all, Beijing has perfected the game of cat and mouse with Covid-19, the Alpha, Beta, Delta variants and seemingly, Omicron too.

For more than two years, Beijing residents had grown used to localised lockdowns, calls for nucleic acid testing and inconveniences that we by now accepted as a part of life in the quest to keep Covid-19 out.

With crisp efficiency, Beijing contained and exterminated the virus each time.

While most of the world remained in various states of lockdown, the city returned to its pre-Covid self by mid-2020. When a family or friend would check in on me, I always responded with: "This is Beijing, the safest place in China."

Now, the city would be facing a crucial test.

The extensive lockdown in Shanghai only proved Omicron's transmissibility.

Stories of frustration about food shortages and lack of access to regular healthcare in Shanghai linger in the minds of my friends and colleagues here.

Before the Sunday announcement for mass testing, rumours of a lockdown had begun circulating after recreational areas silently shut their doors in Chaoyang.

Soon, my WeChat was flooded with survival tips from friends in Shanghai — what items to stock up on, what would be valuable if it came down to barter trading (Coca Cola and cigarettes). Soon, I received pictures of supermarkets wiped out of essentials.

I looked into my kitchen.

Ever since the debacle in Shanghai began, I started amassing necessities during my weekly grocery runs.

Born and bred a Singaporean, the first thing I stocked up on was toilet paper. Over the weeks, coffee, quinoa, all sorts of frozen food and condiments were added, but I forgot about canned tuna.

By the time I logged onto all the grocery apps 20 minutes later, nothing was available anymore.

“The city is not locking down and supplies will not be an issue!” the officials kept repeating.

A close friend, a Malaysian who previously lived in Shanghai and now Beijing, proclaimed that Beijing would not fail, given how crucial was the need to prove that its strategy works best.

I had returned to the city in February 2020, after spending Chinese New Year with my family at home.

This was before the outbreak happened in Singapore and when it was at its worst here in China.

Even then, during the initial confusion, I never had trouble getting vegetables and other ingredients.

Sure, the groceries did not arrive in 30 minutes like they normally did, but nothing that could not be resolved with a bit of planning.

Amid the latest turn of events, this memory from 2020 pushed my anxieties aside. The next morning, the apps were refreshed with stuff again.

I did not make an order, the availability vindicating Beijing’s readiness and echoing their official assurances that there would be no issues with supplies.

Yet, on Monday morning, my confidence was slowly being chipped away as I made the 100m walk to a blue tent outside of my residential compound, set up overnight for nucleic acid testing.

People were returning with trolleys of eggs, milk, vegetables and rice.

An auntie in her mid-fifties had so much food tied to her shared bike she asked the compound’s security guard for help to wheel it.

A young father was dragging a trolley, filled to the brim, with one hand. He held onto his toddler daughter with his other hand.

Would supplies keep up with the stockpiling?

I made more orders of frozen steaks, salmon and prawns on various apps while awaiting my turn for the swab.

When I saw the news about the extensive testing, it was disappointment that bit me.

China was on its way to easing up, testing a 10-day quarantine period for people returning from overseas and rolling out self-test kits.

This would represent marked progress from the current 21-day quarantine and further observations after the quarantine period.

It had been two years, two months and nine days since I had seen my family.

No direct flights between Singapore and the city, protracted quarantine in a port of entry upon return to Beijing and constantly changing rules with regards to entry into Beijing had kept me away.

At the rate this is going, China is going to close up before it eases up again.

On Tuesday, after leaving the office at 5.10pm, I went to join some friends for dinner.

One of them said she had brought forward her departure to the United States, afraid that a lockdown would upend her plans.

Another commented: “Let’s have a good meal today for who knows what is going to happen tomorrow.” We laughed over it.

As we were waiting for our Didi ride-hailing vehicles after dinner, I received a call. It was the city’s disease prevention centre.

“You have come into close contact with a positive case, we might need to take you in for quarantine.”

It was a delivery man who had delivered my lunch six days earlier who had tested positive.

The guy at the other end of the line sounded tired. There must be a lot of people to call.

The instructions were simple enough: Stay at home until we confirm if you need to be taken in or not.

The best case scenario is a 14-day home quarantine. I had by this time accumulated enough food for that period of time.

The worst case scenario was a stay at a quarantine facility.

I ran through my head of what to pack immediately. There were no goodbye hugs for departing friends, just in case.

But I offered some silent apologies for my Didi driver, for I had disrupted his livelihood, as he would find out soon enough.