Once a model of economic development, South Korea now worries Chinese competition will cause a long-term slowdown

From the growing and potentially existential threat from Chinese competitors to a rapidly ageing population, the South Korean economy must quickly transition to a new growth model, experts say, or risk a long-term slowdown akin to neighbouring Japan.

A worker leaving his office in Seoul. President Moon has pushed policies to improve working conditions and increase wages in the hope that rising consumption will trigger a virtuous cycle of employment and growth.

SEOUL - In the corridors of power in Seoul, among the policymakers, economists and businesspeople who drive Asia’s fourth-largest economy, conversation is dominated by one unlikely topic: crisis.

From the outside this may seem odd, given the South Korean economy appears in robust shape. Growth this year is forecast to be just under 3 per cent, while exports remain buoyant and unemployment less than 4 per cent.

But these indicators mask a stark reality for the one-time Asian tiger economy.

Looming on the horizon sits a confluence of factors that economists believe could dramatically impact the country’s growth trajectory, unless the government begins serious structural reforms immediately.

From the growing and potentially existential threat from Chinese competitors to a rapidly ageing population, the South Korean economy must quickly transition to a new growth model, experts say, or risk a long-term slowdown akin to neighbouring Japan.

“We are at a watershed moment,” says Yoon Jong-won, an economic adviser to South Korean president Moon Jae-in.

“If we don’t address past economic problems and if we go ahead as is, uncertainties over our growth trajectory will increase further.”

The issue is one close to the heart of the president, who swept to power last year on the back of economic pledges to improve people’s livelihoods and make South Korea a more equitable nation.

But more than one year into his five-year term, Mr Moon’s economic plans have yet to gain traction and amid sliding approval numbers the 65-year-old is beginning to show signs of anxiety.

“We must at least be able to give hope to the people that our economy will recover,” he said recently.

Critics argue a more fundamental approach is required.

“We need total structural changes on every level — the societal level, the government level, the corporate level,” says Eom Chi-sung, deputy secretary-general of the Federation of Korean Industries.

“We need a kind of spiritual revolution.”

Ulsan, home to Hyundai’s heavy and automobile industries, was once South Korea’s fastest-growing and wealthiest city. Today, it represents the nation’s rust belt, the human toll of economic decline evident in the increasing spate of suicide attempts. Photo: Bloomberg.

At the crux of the issue is the notion that South Korea’s economic model is no longer competitive.

For decades, the economy boomed — and citizens prospered — on the back of a handful of industrial conglomerates, which proved adept at “fast following” the manufacturing output of western and Japanese companies, typically at more competitive prices.

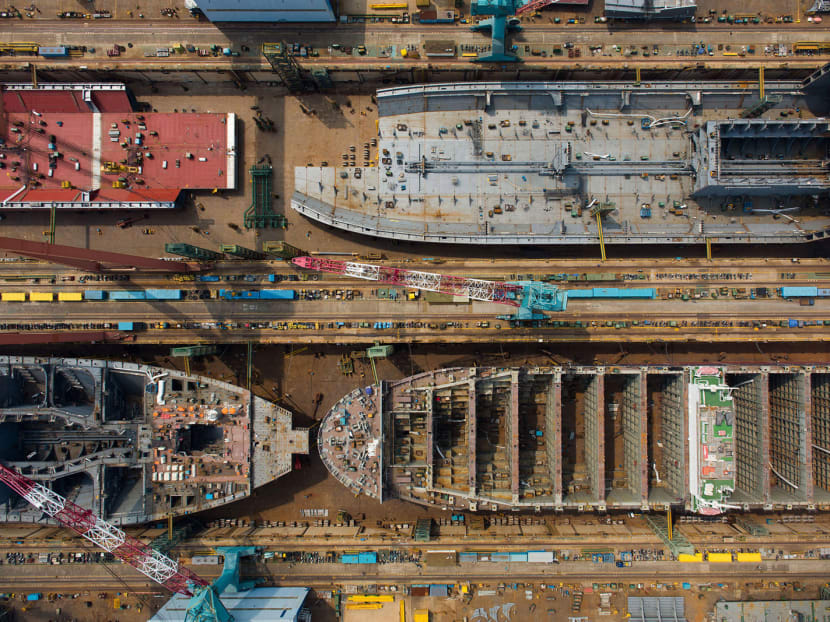

Bolstered by government support, the likes of Hyundai and Samsung threw themselves into sectors such as shipbuilding, automobiles and electronics, and proved tremendously successful around the world.

At one point exports accounted for more than 55 per cent of South Korea’s gross domestic product. Today exports remain solid and are worth more than 40 per cent of GDP.

But South Korea’s competitive edge now risks being eroded and the culprit sits next door: China.

“South Korea’s manufacturing sector is in crisis,” says Oh Se-jung, a member of the National Assembly, pointing to the nation’s declining global share of shipbuilding, automobiles, steel and even mobile phones.

In shipbuilding, for instance, South Korea has seen its market share decline in the past decade from 35 per cent to 24 per cent, while China’s has almost doubled, according to Clarksons Research.

“South Korea can no longer be competitive using second-mover advantages . . . due to the competitive threats from China and India. South Korea does not have its own accumulated know-how, either.”

The bleak outlook is borne out across the country as industrial hubs shed tens of thousands of jobs.

Ulsan, home to Hyundai’s heavy and automobile industries, was once South Korea’s fastest-growing and wealthiest city.

Today, it represents the nation’s rust belt, the human toll of economic decline evident in the increasing spate of suicide attempts (nearly 200 so far this year).

Young people are also fleeing: having quadrupled since the 1970s, the population of Ulsan began to decline in 2016.

Ulsan is just one of nine regions the government has dubbed “industrial crisis zones” and earmarked for almost US$1 billion (S$1.37 billion) in support.

Seoul is also in the process of implementing a US$3.5 billion supplementary budget to create jobs and tackle youth unemployment, which remains intractable at about 10 per cent.

Critics, however, have derided such measures as merely a stopgap approach, aimed at propping up industries that are fundamentally unsustainable, rather than addressing the underlying structural problems.

“Korea needs to focus on research and development and securing cutting edge technologies. China is rapidly gaining on South Korean companies with massive investments,” said Yang Joon-mo, an economics professor at Yonsei University.

Lee Soo-hyun, a research associate at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, echoed the sentiment, saying that the core issue not being addressed is the country’s dependence “on exports that are being driven by big conglomerates”.

“Ultimately it is the conglomerates that decide the strategic industries of Korea, as opposed to Korea deciding those industries.”

The perception that the country is dependent on its biggest companies was reinforced this month when Samsung — by far South Korea’s largest and richest conglomerate — unveiled a US$160 billion investment plan aimed at securing growth amid the rising threat from Chinese competitors.

Almost US$100 billion of the funds was allocated to capital expenditure, with the bulk of that directed toward a single business: semiconductors.

In hot demand from global technology companies that require ever-greater data storage, memory chips have underpinned Samsung’s soaring profits for the past year.

They have also propped up the nation’s exports.

According to the Hyundai Research Institute, semiconductors have accounted for as much as 20 per cent of exports so far this year, up from 12 per cent in 2016.

But Chinese groups are eagerly eyeing the sector — and they have government backing. Under the Made in China 2025 blueprint, Beijing has made clear it wants to dominate high-tech industry.

“On the export side, we have a problem: our biggest customer [China] has become our competitor,” says Peter Kim, an investment strategist at Mirae Asset Management in Seoul.

“The only thing holding up right now is semiconductors.”

One prong of Mr Moon’s economic agenda is to nurture what his administration is calling “innovative growth”. Photo: Bloomberg.

For its part, the Moon administration has crafted a dual-pronged economic strategy. The first is “income-led growth”.

Mr Moon has pushed policies to improve working conditions and increase wages in the hope that rising consumption will trigger a virtuous cycle of employment and growth.

“In the past, our economic growth was mostly export-driven, but we are now seeing more balanced growth with private consumption picking up and solid wage growth,” said Mr Yoon, the economic adviser to the president.

The policy, however, has already run into resistance from the legions of largely unprofitable small and medium-sized enterprises, which cannot afford to pay increased wages.

Soaring levels of household debt — about US$1.15 trillion — has also acted as a damper on consumption.

The other prong of Mr Moon’s economic agenda is to nurture what his administration is calling “innovative growth”.

Aware of the threat posed by China, Seoul has indicated it will pursue vast deregulation to encourage “value added” high-tech industries and boost productivity, which by some metrics is only half the rate of the US.

Central to this is creating what Mr Yoon calls a “level playing field” for start-ups and small businesses, which have long been stymied by the market dominance of South Korea’s sprawling conglomerates — the chaebol.

“The chaebol have made many contributions to our economic development by paying taxes and creating jobs. But they are now . . . taking unfair gains through unfair intragroup deals. This hinders fair competition.”

Kwon Goo-hoon, an economist with Goldman Sachs, says he is optimistic the South Korean economy could move up the value chain, given its strong technology sector as well as its well-educated population.

The key, however, would be whether it could embrace “more, not less” globalisation.

“What we should watch is not whether a particular route [South Korean companies] are taking is right or wrong, but rather how they execute and change and whether they are open to a new way of doing business, especially with globalisation,” he said, alluding to the prevalent idea that few of South Korea’s companies are truly global in outlook and operations.

“A lot of people now have a negative view of globalisation, but in the case of Korea, which has demographic headwinds, globalisation will be crucial.”

Demographics remain one of South Korea’s biggest challenges and one that successive governments have failed to address.

The nation of 50 million has one of the world’s most rapidly-ageing populations. By 2060, more than 40 per cent of citizens will be over the age of 65, up from about 13 per cent now.

The percentage of the population that is of working age — defined between 15 and 65 — peaked in 2016 at 73 per cent and is projected to drop to 50 per cent by 2060.

“The Korean economy faces a number of structural challenges that hamper its long-term growth prospects. The main one is the unfavourable demographics,” says Edda Zoli, an economist with the IMF.

The demographic crunch, combined with the threat to industry from China, has prompted many to believe South Korea is destined for a prolonged period of reduced growth and inflation — a situation that Japan has experienced for the past two decades.

“We cannot avoid what Japan has gone through,” said Park Chong-hoon, head of research at Standard Chartered in Seoul.

“The key now is to how we can minimise the impact of Japanisation and how we can delay Japanisation.”

Ms Zoli acknowledges the parallels between South Korea and Japan, but points out Japan’s “so-called lost decades were . . . the consequence of a series of exogenous shocks”.

South Korea also has several policy tools available to reinvigorate growth, she says, arguing that Seoul should use its “substantial fiscal space” to support labour and product market reforms.

“[South] Korea has one of the soundest fiscal positions among advanced economies,” she says.

It is a reality that South Korean officials finally appear ready to acknowledge.

On Aug 16, Kim Dong-yeon, the finance minister, pledged to increase the rate of budget spending by 7.7 per cent next year, up from 5.7 per cent this year.

“The positive in all this is when Korea gets cornered into a crisis, it brings out the best [in people],” said Mr Kim, the investment strategist, pointing to the country’s experience during the 1997 Asian financial crisis when thousands of citizens donated gold possessions to the government to help weather the storm.

“We’ve always had to fight.” THE FINANCIAL TIMES

A peace dividend? Seoul sees potential economic boost from North Korea

Amid the challenges facing the South Korean economy, there are also opportunities. In Seoul, there is growing excitement that the potential opening of the North Korean economy could prove a boon for the South.

“Our new growth engine can be found in inter-Korean economic co-operation, combining the South’s capital and technology with the North’s inexpensive labour as well as its land,” said Cho Bong-hyun, vice-director of the IBK Economic Research Institute.

It is a prospect of which the Moon Jae-in administration in Seoul appears to be keenly aware.

As geopolitical tensions cooled this summer, the South Korean leader has pushed for deeper economic co-operation with Pyongyang, a move that could incur the ire of the US.

Mr Moon announced last week that Seoul would establish road and rail links with the North by the end of the year and would work towards setting up an “Asian railroad community”, which he hopes can serve as a precursor to a regional trading bloc.

The plans could add more than 1 percentage point to South Korea’s annual gross domestic product and would create more than 700,000 jobs in the next five years, according to a study by the IBK institute.

The road map would also effectively end South Korea’s “island” status by integrating it into regional energy and transport networks in Russia and China. In the longer term, a unified peninsula “could overtake France, Germany and possibly Japan in terms of GDP in US dollar terms, should the growth potential of North Korea be realised”, according to a report by Goldman Sachs.

While Chinese companies appear best placed to tap the North Korean market, South Korea’s conglomerates are also eagerly awaiting the opportunity.

Steel and cement groups that could build new infrastructure have seen their stock prices soar.

“Economic collaboration with North Korea is our big hope,” said Lee Won-il, chief executive of Zebra Investment Management in Seoul.

“Other than that, the outlook looks gloomy.” FINANCIAL TIMES