The Big Read: Pakatan Harapan banks on Malay tsunami to capture Putrajaya

SINGAPORE — Malaysia’s disparate opposition parties have long been criticised for failing to get their act together as a coalition, particularly in naming a prime ministerial candidate and finalising seat allocations in the run-up to the country’s general elections.

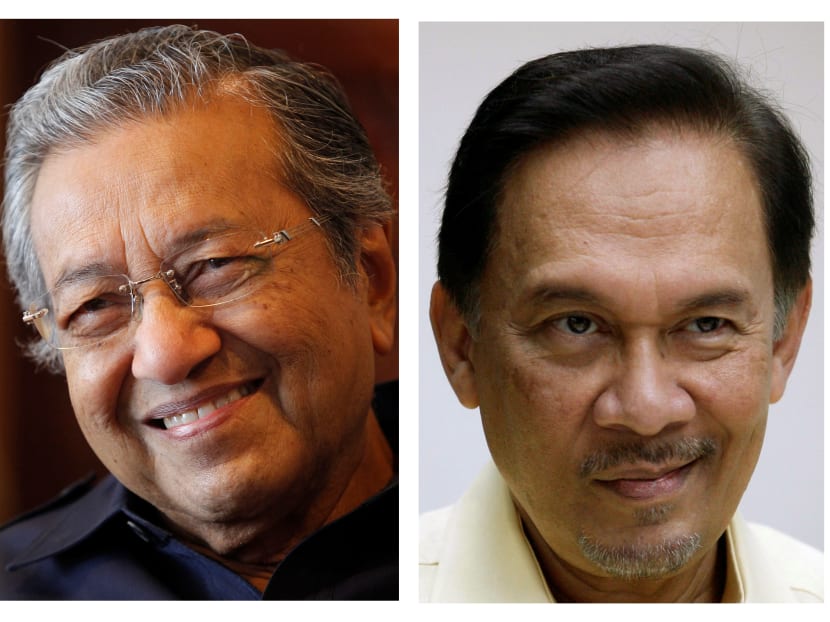

Malaysia's former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad (L) and jailed opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim in their offices in Malaysia on May 4, 2011 (L) and March 11, 2010. Reuters file photo

SINGAPORE — Malaysia’s disparate opposition parties have long been criticised for failing to get their act together as a coalition, particularly in naming a prime ministerial candidate and finalising seat allocations in the run-up to the country’s general elections.

So when Pakatan Harapan (PH) announced last Sunday (Jan 7) that chairman Mahathir Mohamad would be its PM-candidate, and that its four component parties have agreed among themselves who will contest each of the 165 parliamentary seats in Peninsular Malaysia, observers hailed it as a significant sign of unity in the opposition pact.

Dr Mahathir’s fledging Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) will contest 52 seats, while Anwar Ibrahim’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) will vie for 51, with 35 going to the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and the remaining 27 to the Parti Amanah Nasional (Amanah).

Opposition politicians told TODAY that the move to nominate Dr Mahathir and give Bersatu the most seats — pitting it directly against the United Malays National Organisation (Umno) — had one overarching objective: To engineer a “Malay tsunami”, which is critical to PH’s bid to take over Putrajaya.

“PH parties have contrasting ideologies …people are sceptical if we could work together, so there is a need to make a declaration that we are united and have settled everything,” PKR vice-president Chua Tian Chang said.

“This is also a question of timing. With the election being so close, we have to set the pace for people to know where we are heading.”

Leaders from opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan (PH) pose for a photo while holding up posters of the coalition's logo. PH’s move to name Dr Mahathir Mahathir as its prime minister choice had one objective: to engineer a “Malay tsunami” critical in PH’s bid to take over Putrajaya. Photo: Malay Mail Online

While Umno leaders have poured scorn on Dr Mahathir’s nomination, political analysts say that he cannot be written off easily.

The former premier retains some influence among the Malays, and his track record in bringing progress to Malaysia could appeal to voters disgruntled by the rising costs of living.

But the nomination of the 92-year-old and the understanding that he would make way for Anwar, 70, if the latter succeeds in getting his five-year ban from politics overturned also point to a long festering issue: the lack of leadership renewal in Malaysian politics, particularly within the opposition.

Ultimately, while PH has sent a clear signal of its intent to break Umno’s stranglehold on Malay and rural seats, it faces long odds in its bid to win power, experts say.

THE MALAY GROUND STRATEGY

The opposition created history in the 2008 general election when it denied the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) the two-thirds parliamentary majority it had enjoyed for decades. The northern state of Penang, as well as Malaysia’s richest state, Selangor, fell, and have remained under Pakatan’s rule since.

In the 2013 polls, the opposition won the popular vote for the first time, securing 50.9 per cent of the votes, compared to BN’s 47.4 per cent.

But BN returned to power by winning 133 of 222 parliamentary seats, down from 140 in 2008.

BN’s victory was attributed to it faring better among Malay voters, as the opposition’s vote share among the Malay electorate decreased from 41 per cent in the 2008 polls to 36 per cent five years later.

PH has long struggled to make a serious dent in BN’s Malay and rural support bases, to which the ruling coalition has pledged billions of ringgit in aid and infrastructure, most recently during Prime Minister Najib Razak’s 2018 Budget in October last year.

Umno leaders have also warned repeatedly that if the opposition wins the election, then Muslim Malays — about 60 per cent of the country’s 32 million people — “will become homeless and despised in their own country”.

As the party plays up its credentials as champion of Malay rights and defender of Islam, its leaders have also charged that PH is secretly dominated by the Chinese-majority DAP and that the special position and rights of the Malays in the country would be eroded if the DAP came to power — a claim which the opposition party has consistently denied.

The entry of Dr Mahathir’s Bersatu — which has positioned itself as a Bumiputera party — into the opposition fold could turn PH’s fortunes around, especially among the Malay rural electorate.

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad waves as he leaves after he was stopped from visiting jailed opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim who is recuperating from a surgery at Cheras Rehabilitation Hospital in Kuala Lumpur. Photo: Reuters

Notably, the coalition’s youngest party is not only contesting the lion’s share of the seats, but most are in areas with Malays making up over 60 per cent of voters.

Malaysia’s Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (Ideas) chief executive Wan Saiful Wan Jan said PH’s nomination of Dr Mahathir to the country’s top post sends a strong message aimed at “neutralising the fear-mongering by Umno that the DAP and the Chinese are controlling PH and pulling the strings behind the scene”.

PH insiders told TODAY that an internal survey found Dr Mahathir was the number one choice for prime minister among the rural electorate, with many hankering for a return to the golden age of Malaysia — the 22 years with Dr Mahathir at the helm, when the economy grew rapidly.

“Malaysians, especially the younger generation, grew up learning in schools that Dr Mahathir modernised the country, improved the lives of the Malays,” said ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute senior fellow Dr Lee Hock Guan, who adds that some voters even believe that the former premier can “bring back that buzz again.”

“So, BN has a major problem in discrediting him.”

Dr Mahathir is also considered a “rebel” by some Malay voters looking for someone to champion their disenchantment with BN.

Non-Malays and the urban Malay middle class, meanwhile, want Anwar as prime minister, as many consider him the best choice due to his experience both within and outside the government.

“We are addressing the problem that has been plaguing us and prevented us from winning decisively in the past elections, namely, gaining the confidence of the Malay voters. They want change, but they were not confident that PH had the leadership back then,” said Amanah’s communications chief Khalid Samad. “So to ensure their confidence in us, the only solution is to name both Dr Mahathir and Anwar. It is a logical thing to do, and I believe we have the winning formula now.”

PH’s early resolution of the thorny issues of the premiership choice and seat allocation is based on the opposition’s experience in the run-up to the 2008 polls.

During that time, Anwar and DAP secretary-general Lim Guan Eng agreed on seat allocations and leadership of Penang on Jan 9, three months before the general election.

PH leaders believed this was an important factor in the opposition’s clinching of the northern Malaysian state.

“The move definitely gave us the strength of clarity and certainty to our campaign at that time, and we believe it will be equally successful this time,” said Penang DAP political education director Steven Sim. “One sorts out one’s own home (first), and then focuses on winning.”

Umno leaders have brushed off the threat posed by Dr Mahathir and PH, calling his nomination “regressive” and his tie-up with the opposition a “political charade”.

Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi even said sarcastically that there was no other person more qualified to bring damage and ruin to the country than Dr Mahathir.

Umno’s Johor assemblyman Tengku Putra Haron Aminurrashid Tengku Hamid Jumat told TODAY: “There has been too much bad blood between the parties in PH in the past. They will not last long as a coalition if they succeed in GE14, and if they were to break up, it will cause irreparable damage to the nation.”

He added that Umno has seen its rejects lead parties in the opposition for decades, but it has always prevailed because it “is the most organised political outfit in Malaysia”.

“We may not be perfect, but we are the better party,” he added.

The selection of Dr Mahathir as candidate for the premiership and Anwar as his replacement points to both a lack of leadership renewal in the opposition and the desire of both these veteran politicians to wield power, say observers, who note that most of the younger politicians in PH are too inexperienced to mount a leadership challenge.

Malaysia's former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad (centre L) meets with jailed opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim (centre R) in a high court in Kuala Lumpur. Photo: Reuters

These include Anwar’s daughter and PKR vice-president Nurul Izzah Anwar, Dr Mahathir’s son Mukhriz Mahathir, and PKR deputy president and Selangor Chief Minister Azmin Ali.

Others, such as Bersatu president and former deputy prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, are seen as inferior to Dr Mahathir and Anwar in terms of “political impact”, a PH leader who is privy to the details of the coalition’s strategy told TODAY.

“The leadership renewal is a sad situation. Those at the top just can’t let go,” said Mr Wan Saiful of Ideas, noting that with a dearth of younger leaders, PH has decided to bank on “a larger than life figure like Dr Mahathir.”

However, PKR’s Mr Chua defended the opposition’s strategy, pointing out that PH has second-tier leaders in the wings, but Malaysians may not feel that they are ready to take over at this stage.

“People want the transition (of PH taking over from BN) to be as painless as possible... there is a large middle class in Malaysia who do not want to see any destabilising period.”

WHAT ABOUT SABAH AND SARAWAK?

PH’s announcement last Sunday had one glaring omission — there were no details about what plans, if any, it had to contest Sabah and Sarawak.

Observers point out that for PH to have a chance to become the ruling government, it needs to break the stranglehold that BN has over the two Borneo states.

Both are considered “fixed deposits” — sure wins — for BN. In the 2013 general election, Sabah and Sarawak delivered about a third of the 222 parliamentary seats to the coalition.

By contrast, DAP and PKR collectively won only nine parliamentary seats in the two states.

In the 2016 Sarawak state election, BN swept 72 of the 82 seats available and garnered 63.72 per cent of the popular vote, prompting PM Najib to declare that support for the government and BN “is solid”.

PH’s secretary Saifuddin Abdullah downplayed the issue.

“It is up to our brothers and sisters who have started discussions on seat divisions a couple of months ago with the local independent parties to announce the matter later,” he said, referring to the myriad parties in the two states due to their diverse racial mix.

Nevertheless, analysts are dismissive of PH’s chances of gaining a strong foothold in Sabah and Sarawak.

Dr Mahathir could also prove to be a liability for PH in Sabah, due to the controversial “Projek IC” he was said to have initiated during his time as premier, which allegedly involved giving illegal immigrants in the state citizenship in return for votes.

This led to what Malaysian media described as an “abnormal spike” in Sabah’s population.

PH also is unable to come to an agreement on the non-Muslim Bumiputera seats in Sabah, said ISEAS’ Dr Lee, who voiced pessimism that it can reach a consensus on this at all.

“If they cannot agree on the seat allocations at this point, then their chance of winning will diminish,” he added.

THE QUESTION OF PAS

Despite a mood of optimism in PH, most observers think BN is expected to retain power as the electoral system is stacked in favour of the incumbent.

The slight uptick in the economy, with GDP growth expected to be at 5.2 per cent this year, in contrast to under 5 per cent growth in 2016, is also likely to benefit BN.

The ringgit also rebounded from a 19-year low last year to become Asia’s second-best performing currency for 2017.

Another factor not in PH’s favour is that it may not be able to count on young voters this time round.

Youths who came out in droves to vote for the opposition in the last two elections may stay away this time because of political fatigue and apathy.

A survey by Malaysian pollster Merdeka Centre in August found that seven out of 10 young Malaysians said they found politicians to be untrustworthy and the main cause of problems in Malaysia; two-thirds said they did not care for politics, while four in 10 were not registered to vote.

PH seems to be aware of the problem and is wooing the young with pledges that matter to them: It has proposed that the minimum wage be raised from RM1,000 (S$334.6) to RM1,500, has promised to abolish the unpopular Goods and Services Tax and has offered RM100 unlimited travel cards for commuters who use public transport.

Still, other obstacles remain. The role that will be played by Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), which has pledged to contest up to 120 seats nationwide, is one issue that has divided analysts.

PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang. Photo: The Malaysian Insight

Some think this stance could hurt Bersatu and PAS’ splinter party, Amanah: Malaysia uses a first-past-the-post electoral system, and three-cornered fights have traditionally favoured BN, they say.

Others, however, have expressed doubts over the impact that PAS will have on the outcome of the election.

Factors such as the ratio of Malays and non-Malays in the constituencies where PAS will contest are important too, they say.

The party’s warming ties with BN could also backfire — the Islamist party’s grassroots members and supporters might be displeased by this, said Dr Chandra Muzaffar of the foreign policy think tank International Movement for a Just World.

One thing is clear: With Umno, PAS, Bersatu and Amanah all gunning for the crucial Malay vote bank, the fight will be furious.

DAP lawmaker Liew Chin Tong, for one, added that PH has an edge this time round because of last Sunday’s events.

The early decisions on seat allocation and the nominee for PM will enable its candidates, election machinery and voters to focus on the looming battle, he said.

“This is the first time in history that the seats agreement was finalised so early before the polls, and this is good for us to position ourselves and move as a strong unit towards the election,” he added.