South Korea set to reverse decades-old policy on international adoptions

SEOUL — International adoptions from Korea have slowed down drastically in recent years amid government efforts to ratify the Hague Convention on adoption, and is expected to become a rarity soon.

Holt Children’s Services, one of the three main adoption agencies in South Korea, said the bleaker prospect for orphans finding homes was a “big concern”, and more than 300 children yearly are less likely to be adopted. Photo: Toh Ting Wei

SEOUL — At barely six months old, Ms Anne Katrine Salling was left on a street in Seoul.

Her mother had abandoned her.

A year later, she was embraced by a new family — in Denmark.

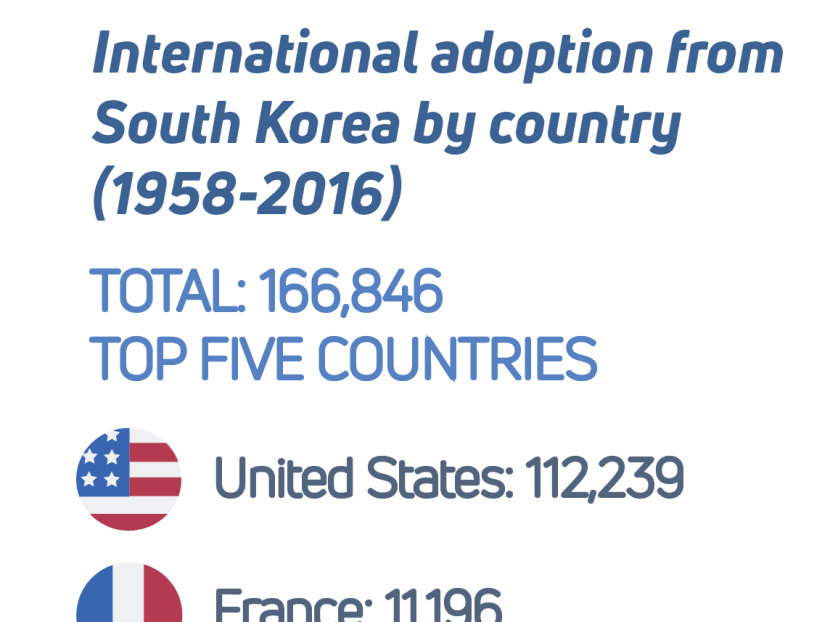

Ms Salling, now 44, is one of the 166,846 Korean orphans who have found new families overseas since 1956, as a result of a fluid adoption system that established South Korea as one of the top countries for international adoptions.

But international adoptions from Korea have slowed down drastically in recent years amid government efforts to ratify the Hague Convention on adoption, and is expected to become a rarity soon.

South Korea signed the Convention, which states children should preferably be adopted domestically, in 2012.

It has tried to ratify the Convention since 2014, but without success.

The attempt has sparked concerns that more orphans would grow up in local orphanages without a family.

Infographics: Kelley Lim

Already fewer orphans are getting adopted. International adoption fell to 334 in 2016, from 916 in 2011.

Meanwhile, domestic adoption dropped from 1,548 to 546 over the same period.

Holt Children’s Services, one of the three main adoption agencies in South Korea, said the bleaker prospect for orphans finding homes was a “big concern”, and more than 300 children yearly are less likely to be adopted.

Holt handled about 100 of the 334 international adoptions in 2016.

“In our country, domestic adoption will remain around the same, and international adoption will decrease,” said Ms Lee Eun Jeong, manager of international adoption and fundraising at the non-profit agency.

“The needy children will go to orphanages because adoption agencies cannot take care of children anymore, and this contradicts the Hague Convention which advocates that every child should have a home.”

American housewife Jess Rieger, 30, who is eight months into the process of adopting a Korean orphan with her husband, said that if South Koreans are unwilling to adopt children in their own country, the new laws would be a disservice to orphans who need homes.

“The challenges we have experienced have not deterred us, but they have been discouraging,” she said.

South Korea started allowing international adoption in 1956 after the Korean War, amid a boom in mixed-race babies arising from relationships between United States servicemen and South Korean women.

Holt’s founders, Americans Harry and Bertha Holt, paved the path for other adoptive families after they successfully urged the US Congress to pass a special act that allowed them to adopt eight Korean children.

The US has the largest number of adoptions from South Korea, with 112,239 babies officially adopted in the past six decades. France and Denmark come in a distant second and third with 11,196 and 8,792 Korean children adopted respectively.

Boys are more commonly put up for international adoption, with girls favoured for adoption at home, said social workers.

The Confucian ideals of the South Korean society place a heavy emphasis on blood relations, and most locals are reluctant to accept the idea of an adopted son carrying on the bloodline and family name, social workers added.

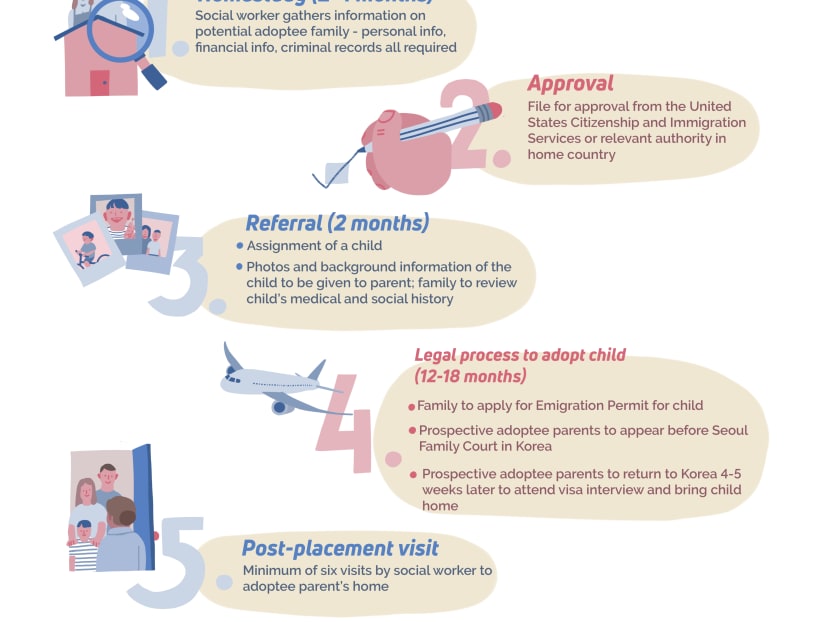

The process of international adoption today can take more than two years, and requires a home study, two trips to Korea and court hearings, among other demands.

Prospective adoptive families and Holt said the process costs about US$40,000 (S$54,170).

When the changes to Seoul’s adoption system began in 2012, a special government-linked agency, Korea Adoption Services (KAS), was set up to align processes with requirements by the Hague Convention.

KAS has been earmarked to become the central authority to handle all adoptions once the Hague Convention has been ratified.

A staff member at KAS, who asked not to be named, said: “Sending out too many children is kind of shameful, so many politicians and South Koreans feel that we have to stop overseas adoption.”

Criticism of the outflow of babies through international adoption has intensified in recent years as Seoul grapples with a declining birth rate, which President Moon Jae-In said is expected to fall to a record low of 1.03 per woman in 2017.

Some returning Korean adoptees who spoke of their negative experiences have also turned public sentiment against foreign adoptions, said social workers.

Ms Salling, now secretary general at adoptee support group Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link, said: “Even if adoptees grew up in a loving family, they could still have identity and mental health issues, among other problems.”

But ratification of the Hague Convention has been slower than expected, as the country struggles to untangle a system that has endured for over half a century.

“The government wants to ratify the Convention this year, but it depends on the National Assembly and the many stakeholders,” said the KAS’ staff member.

“The adoption agencies here are very big, so their voices affect politicians.”

Adoption issues are currently managed by three main private agencies: Holt, Eastern Social Welfare Society and Social Welfare Society.

These agencies will have to hand over responsibility to the government in order for the Hague Convention to be ratified, said the KAS staff member.

Boys and disabled children will be most affected by increased restrictions on international adoption, said Mr Lee Jong Rak, a pastor at the Jusarang Community Church.

Pastor Lee started Babybox, an initiative for single mothers to leave infants for the church to pick up.

The Babybox has received 1,200 babies in seven years. The number shot up to 223 last year, from just four babies in 2010. “Most children with disabilities tend to be sent to orphanages, but people from other countries, especially Americans, are more open to adopting them,” said Pastor Lee.

He has adopted 18 children with disabilities.

South Korea aims to address the impact of reduced foreign adoption with a two-pronged approach.

Besides promoting domestic adoption, the government is encouraging single mums to raise their children, said the KAS staff.

“This is key because more than 90 per cent of orphans are from single mums,” he noted.

“If single mums raise their own babies, the number of orphans will decrease, and we don’t need to think about domestic or international adoptions.”

According to the Korean Unwed Mothers Families’ Association, three in four single mothers give up their children due to economic difficulties and social discrimination.

The government has announced that it wants to increase support for single mums, with the aim of encouraging mothers to keep their children.

But single parents receive only 70,000 won (S$84) per child a month in government support, as compared to the monthly 1.1 million won a child in an orphanage receives, according to the association.

In 2012, a new adoption law was passed requiring birth mothers to register themselves and go to court in order to put their children up for adoption. The aim was to make the adoption process more transparent and help adoptees to trace their birth parents in the future, but it also had the additional of deterring women who did not want to be registered as single mothers.

Social workers said this law, coupled with a falling birth rate, have reduced the number of orphans eligible for adoption.

In 2015, the number of children staying in welfare centres caring mainly for orphans dropped by 26.8 per cent to 12,821, from 17,517 in 2006.

The future holds more uncertainties for orphans.

One option could be foster homes, which would enable orphans to grow up in a family without being legally adopted, said Mdm Kim Ji Hyun, manager at The Salvation Army Broadview Children’s Home.

In such homes, orphans stay with foster families, usually cousins or neighbours, until they grow up, said Mdm Kim, 42.

Holt’s Ms Lee, an adoption worker of 24 years, said that while many social workers still think finding a home Korea is the best option, they cannot be sure what will happen with changes to the adoption process.

“Less than 10 per cent of adopted children have problems with their overseas families and struggle to adapt to their society. So international adoption is still a good opportunity for them to find a family, even though it is not perfect.”

Toh Ting Wei, a final-year journalism student at Nanyang Technological University’s Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, did this report as part of the school’s Going Overseas For Advanced Reporting module. This is part of a series on South Korea that TODAY is running.