The star businessman who ignores his investors to make them rich

TOKYO — When Mr Akira Matsumoto speaks, investors hang on his every word. And here’s what he tells them: you’re less important than everyone else.

TOKYO — When Mr Akira Matsumoto speaks, investors hang on his every word. And here’s what he tells them: you’re less important than everyone else.

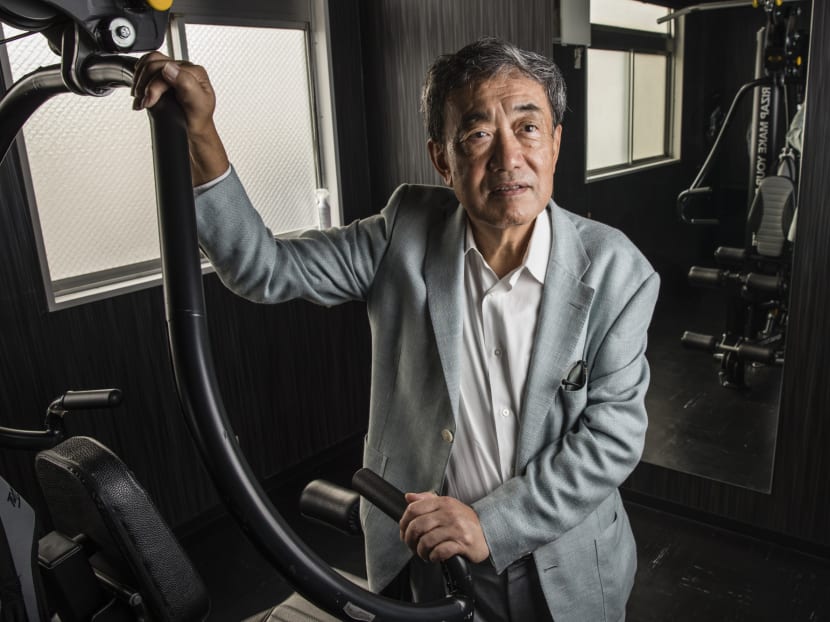

The diminutive 71-year-old can get away with it because of his status in the Japanese business world, where he’s known for his two decades of successfully running big-name companies.

At the food group Calbee, for example, Mr Matsumoto almost doubled sales and increased operating profit six-fold in his nine years in charge. The shares tanked when investors heard he was leaving.

But Mr Matsumoto doesn’t share the love, at least on the surface. Stock owners, he says, come only fourth in his list of priorities, after customers, employees and the wider community. Only by ignoring them — and focusing on the greater good of the company — can he serve their needs.

“It’s shareholders last,” the charismatic Mr Matsumoto said in an interview in Tokyo. “That’s actually the best thing for them.”

It’s a stance that appears to go against the entire tradition of shareholder capitalism. It’s also also a relatively commonly held view in Japan. Billionaire entrepreneurs Kazuo Inamori, who founded Kyocera, and Mr Shigenobu Nagamori, who started Nidec in a shed beside his mother’s farmhouse and turned it into a US$41 billion (S$56 billion) company, have both expressed similar opinions, their success as company leaders perhaps allowing them to say what others think.

But in Mr Matsumoto’s case, the sentiment has its roots in the US. More specifically, it traces back to the credo of Johnson & Johnson, where Mr Matsumoto worked before he joined Calbee.

The health-care company’s statement of values also puts customers first, followed by employees, the community and finally shareholders.

“I adhere to this and I’ll never veer from it for as long as I live,” Mr Matsumoto said.

According to the businessman, putting stock owners first has often got companies into trouble.

“Thinking only about shareholders means thinking only about the bottom line and that leads to all kinds of scandals,” he said. “If you really believe shareholders are important, you have to run the company” in the Johnson & Johnson order, he said.

Of course, some shareholders aren’t too happy to be told they’re last in line.

“I’m always getting complaints,” Mr Matsumoto said. But “I’ve never asked shareholders to buy shares. I tell them that this is the policy I operate under. I tell them I really believe in this policy, and if they believe in it too, they should buy shares. If they don’t like it, they can sell.”

Still, many investors have no problem with Mr Matsumoto’s methods.

“He has a track record that deserves acclaim,” said Mr Mitsushige Akino, a senior executive officer at Ichiyoshi Asset Management in Tokyo.

“I don’t care that he puts shareholders last rather than first. If he gets results, that in itself is putting shareholders first.”

Mr Matsumoto graduated from Japan’s prestigious Kyoto University with a master’s degree in agriculture in 1972 and went to work for the trading house Itochu. He joined a Japanese unit of Johnson & Johnson in 1993 and became president in 1999, a role he stayed in for nine years. He was appointed chairman and chief executive officer of Calbee in 2009.

Calbee’s stock has risen more than six-fold since Matsumoto helped take the company public in 2011. It fell the most in two months in March when he said he was stepping down.

Two months later, the coveted CEO surprised many in Japan when he said he was taking the post of chief operating officer of Rizap Group, a gym operator that’s become known for its TV ads of celebrities before and after they undergo an extensive two-month personal training and supplement program.

The company has also gone on an acquisition spree under its CEO Takeshi Seto. It now has a market value of more than US$3.6 billion.

But if others were surprised, Mr Matsumoto sees nothing strange about the move, or about working for a boss who he says, at 40, is the same age as his son.

“It’s like having a box of toys,” he said of the opportunity to find out more about the many companies that Mr Seto has bought. And “I prefer to operate in stealth behind the scenes.” BLOOMBERG