What is your perfect death? Hong Kong to give terminally ill patients more say over how and where they die

HONG KONG — When 97-year-old Tso Kwan-pui thinks about death, he is certain about one thing — he hopes to die in the care home for the elderly where he has stayed for the past six years, surrounded by people he knows.

HONG KONG — When 97-year-old Tso Kwan-pui thinks about death, he is certain about one thing — he hopes to die in the care home for the elderly where he has stayed for the past six years, surrounded by people he knows.

“It is best to leave peacefully in a familiar place with nice surroundings,” said the former trader, who has five children, eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

When the time comes, he does not want to be sent to the hospital and face resuscitation or forced feeding to keep him alive.

“What’s the point of delaying death and making me suffer for a few more days? If it is my time, I should go,” he said.

For now, if his health took a turn for the worse, the home in Lam Tin would first move him to its hospice room for 24-hour medical care.

Under current Hong Kong laws, however, he would have to be sent to hospital any time death was imminent. The ambulance staff moving him would perform resuscitation, even if he had indicated earlier that he did not want it. And his death would have to be certified in a hospital.

Currently, all deaths in care homes for the elderly must be reported and need follow-up action by police and forensic pathologists, with postmortem examinations if necessary.

The Hong Kong government is planning to change the city’s laws to improve end-of-life care and give people more legal power to decide the medical treatments they receive when terminally ill, and more choices of where to die.

A number of amendments to the law were proposed last month, following a public consultation in 2019.

An amendment to the Coroners Ordinance aims to exclude natural deaths in residential care homes for the elderly and the disabled from being reportable, provided the individual was diagnosed with a terminal illness, had been treated by a doctor within the previous 14 days, and a doctor confirmed the death was not suspicious.

Proposed changes to the Fire Services Ordinance will allow paramedics to respect a patient’s wish not to receive resuscitation.

This would have to be stated in an advance directive, a legal document signed by mentally sound adults indicating the treatments they did not wish to receive when dying.

While currently there is no legislation stipulating the legal status of the document, which has led to uncertainty among patients, the government is planning to give statutory power to the directives under the proposed changes.

The “do-not-attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation” order, currently issued for those who are mentally incompetent or underaged and relied upon when it would be best for them not to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when terminally ill, would also be made on a statutorily prescribed form. First responders complying with these orders would be exempted from legal liability.

Doctors and care home operators who spoke to the Post welcomed the changes, describing them as a big step forward in improving the city’s end-of-life care, but called for more to be done to raise awareness among the public and healthcare professionals.

Dr Tracy Chen Wai-tsan, from the Hong Kong Society of Palliative Medicine, said dying patients deserved to have more control over their lives at home or in care homes, allowing them to spend more time with loved ones during their last days.

“Patients will feel less anxious and more comfortable in a familiar environment,” said Dr Chen, a specialist with more than 20 years’ of experience working with the terminally ill.

Family members could also spend time with the dying person round the clock, unlike in hospitals with fixed visiting hours.

“The hospital environment is noisier, filled with sounds of different machines, and there is less privacy too, with other patients around,” she said.

Welcoming the changes regarding CPR, she said the disadvantages of such resuscitation outweighed the advantages for those who were dying and could lead to broken ribs and bleeding in internal organs.

“The success rate of CPR at this stage is very low, close to zero per cent,” she said. “The treatment is futile, but can bring a lot of discomfort and complications.”

‘THE WHOLE FAMILY CAME TO SAY GOODBYE’

Retiree Yeung Tze-sheung, 61, recalled how he and his family were able to bid goodbye to his mother properly during her last 24 hours at a care home in Tsing Yi in early March.

His 86-year-old mother had been in the home for more than a year when she was moved to a hospice room there. Almost 20 family members managed to see her for the last time.

“We could go one by one to her room to say goodbye,” Mr Yeung recalled. “I told her, ‘Mother, I’m sorry for being naughty when I was small and making you angry.’”

Although his mother was unconscious, family members could comfort her physically, holding her and stroking her face.

“If she was in hospital, it would not have been possible for the entire family to say goodbye,” he said.

His mother passed on before she could be moved to a hospital, so the death had to be reported. That meant police had to follow up, and the body had to be sent to a public mortuary to be checked, involving extra paperwork by the care home.

Mr Yeung said these extra procedures seemed troublesome.

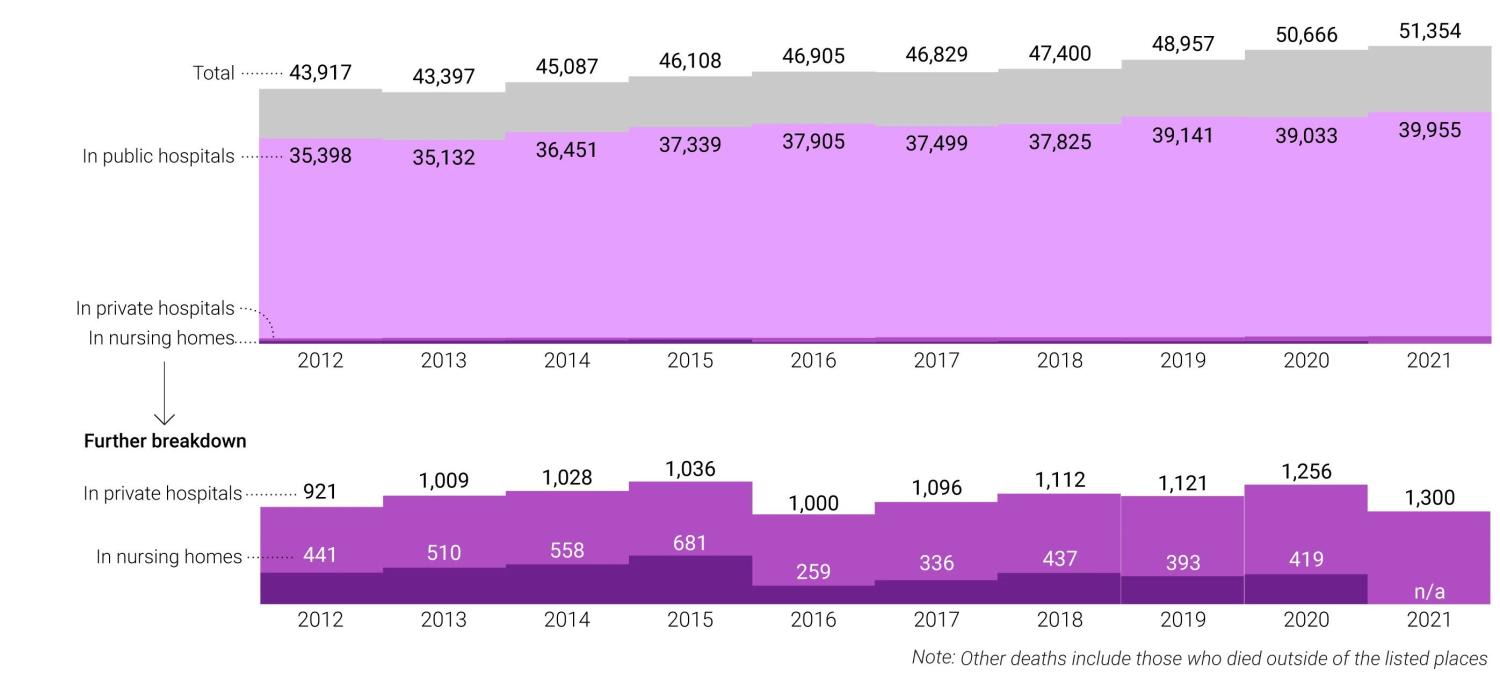

Because of Hong Kong’s current laws, most deaths occur in hospitals. From 2012 to 2021, between 43,000 and 51,000 deaths were recorded each year, with more than four-fifths in public and private hospitals. Most of the rest were at specific licensed nursing homes, before the individuals could be sent to hospital, or at home.

The Covid-19 pandemic gave rise to new demand for dying at home, according to DoctorNow, a company providing medical services to people’s homes.

Mr David Wong Chuk-hin, its chief operating officer, said: “During the pandemic, people didn’t want to be hospitalised as visitors were not allowed. They were also worried about the poor environment in hospital and getting infected there.”

Dying at home does not have to be reported provided the person has been diagnosed with a terminal illness, or was seen by a doctor within the 14 days before death.

Founded in 2015, the company began offering its dying-at-home service in 2019, and handled no more than 20 home deaths the following year. Since then, the number has risen and it has dealt with more than 400 home deaths, mostly at public housing estates or government-subsidised flats.

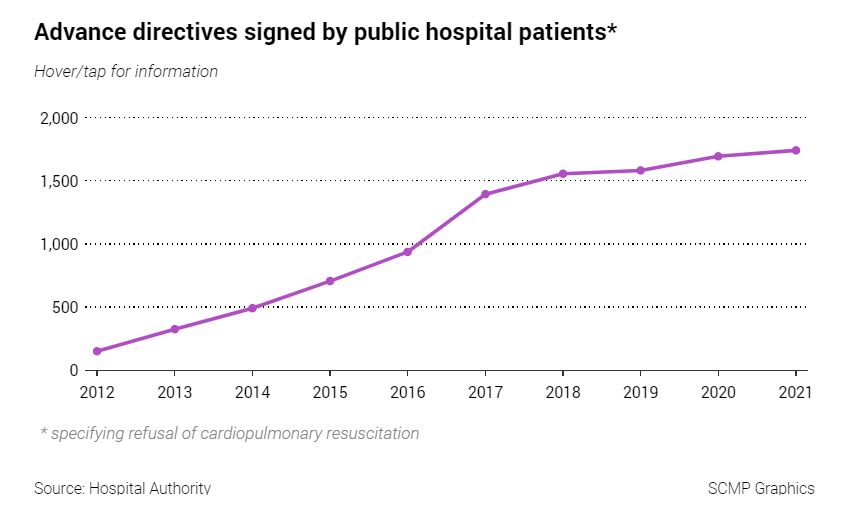

Hong Kong has also seen more people signing advance directives in the past decade. Between 2012 and 2021, the number of medical documents specifying the refusal of CPR signed by public hospital patients increased from 150 to 1,742.

While dying at home was relatively new in Hong Kong, Mr Wong said arrangements for at-home palliative care and death had been done for decades in places such as Taiwan and Japan. Up to two-fifths of deaths in Taiwan happened at home.

Singapore was also aiming to reduce the proportion of hospital deaths from the current 61 per cent to 51 per cent by 2027.

‘WHY CALL AMBULANCE FOR A DEAD PERSON?’

Dr Edward Leung Man-fuk, president of the Hong Kong Association of Gerontology, said he hoped the proposed changes to the law would not only mean better end-of-life care for the dying, but also less pressure on hospitals.

“People can complete their life journey smoothly without affecting services at hospital emergency rooms. Isn’t this better, as you will not waste social resources?” he asked.

“A person is dead already, why do we still have to call an ambulance, do registration in a hospital emergency room, get death certification and send the body to a public mortuary?”

Dr Leung hoped care homes could also provide more palliative care to residents with late-stage illnesses, and avoid sending them to hospital repeatedly.

He said about 10 to 20 out of every 100 care home residents died every year, and an estimated half of the deaths were related to their known diseases such as organ failure, cancer or late-stage dementia.

In the final six months to one year of their life, even when death was inevitable, some of these residents would be sent to the hospital repeatedly, which he described as “torture”.

“They might undergo lots of check-ups and treatments and be discharged, only to be admitted again,” he said. “It is also a suffering for their family members.”

Ms Rebecca Chau Tsang, who runs a care facility for the elderly in Cheung Sha Wan, has already prepared an end-of-life care room even though her residents cannot use it yet.

She said she hoped it would be used once the law allowed certification of deaths in elderly homes. It will need equipment such as electric blankets and a medical bed.

“It can be put into use any time the legislation has passed,” she said. “We hope the elderly can leave well.”

Ms Chau said she hoped that when the time came, the government would give clear guidelines on how to handle natural deaths in care homes.

Paramedics, who would have to comply with advance directives, also looked forward to clear instructions and protection for difficult situations, for example, when family members disagreed over a person’s treatment.

Mr Jang Chun-kit, chairman of the Hong Kong Fire Services Department Ambulancemen’s Union, said: “The elder son might show his father’s advance directive saying no resuscitation is needed, but another son might say their father had hoped to live on. There should be waiver clauses for us if we perform resuscitations.”

‘PRIMARY CARE DOCTORS CAN RAISE AWARENESS’

Medical experts said the changes to the law were an important first step, but more education was needed to raise public awareness of end-of-life care choices, and the care home sector would need attention too.

The gerontology association’s Dr Leung said he expected that the legislative changes would be followed by a rise in demand for palliative services at care homes.

“We need to provide more training to staff at the senior, middle and frontline levels at care homes,” he said.

Palliative medicine specialist Dr Chen said doctors at the primary healthcare level could help to promote end-of-life education with their patients and look into advance care planning.

“When people come for health check-ups or with minor ailments, the doctors could provide some education, in a more ideal environment to discuss advance care planning and advance directives.”

Chinese University professor and former health minister Yeoh Eng-kiong, who completed a government-commissioned study in 2017 looking at the city’s end-of-life care, said primary care doctors could also provide practical support to patients hoping to die in the community.

District health centres could coordinate their networks of primary care doctors to provide palliative care, including pain control, to those dying at home, he said.

Prof Yeoh also said he believed the legislative changes could prompt more people to think about plans for their final days.

“Once we talk about this, people need to understand the decisions you make for [the time] when you don’t have the mental capacity. Everyone’s timing is different, but at least you start this, you have an instrument,” he said. SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST