Why Malaysians are slow to board their new trains

KUALA LUMPUR — Prime Minister Najib Razak likes to show off his role in expanding Kuala Lumpur’s rail network, first launched by his predecessor Mahathir Mohamad in the 1990s.

An MRT train coming towards Taman Midah station, against the backdrop of the Kuala Lumpur city skyline. Kuala Lumpur has the lowest proportion of people using public transport despite having the most developed rail network. Photo: TODAY file picture

KUALA LUMPUR — Prime Minister Najib Razak likes to show off his role in expanding Kuala Lumpur’s rail network, first launched by his predecessor Mahathir Mohamad in the 1990s.

A video of Mr Najib praising the capital’s newest line as one of the world’s best blares on the trains in a continuous loop, functioning as campaign material ahead of the general election this year.

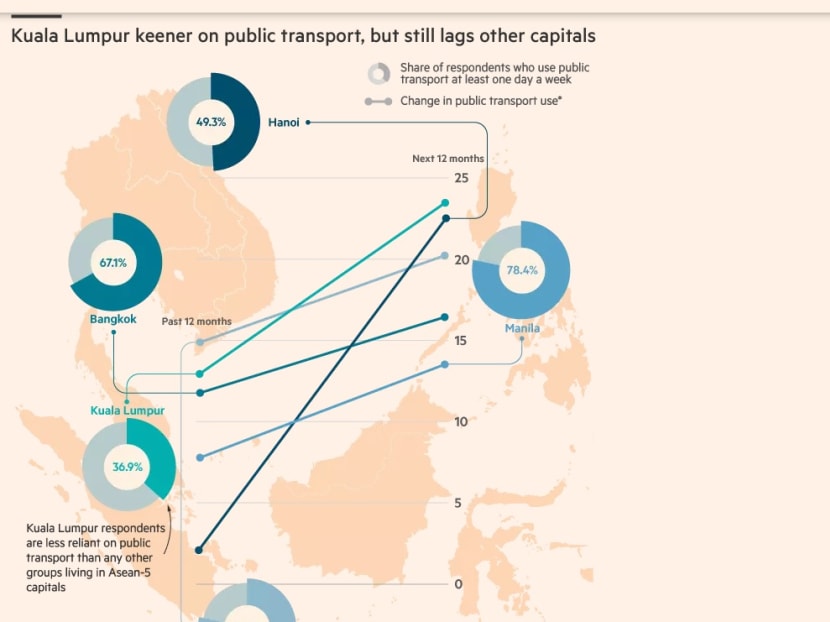

The network expansion has made a difference. FT’s fourth quarter 2017 survey showed a larger rise in public transport use in Kuala Lumpur than in the other Asean-5 capitals, except Jakarta.

The same survey also suggests that the number of people using public transport in Kuala Lumpur will grow strongly this year.

Even so KL, as the locals call the city, has the lowest proportion of people using public transport despite having the most developed rail network).

Malaysia has the highest passenger car ownership rate in Southeast Asia. Based on official government data, the country had an estimated 415 passenger cars for every 1,000 people in 2017.

Thailand, Asean’s car manufacturing hub, was second with 166 passenger cars per 1,000 people. This dependence on private cars has led to Kuala Lumpur’s congestion problem.

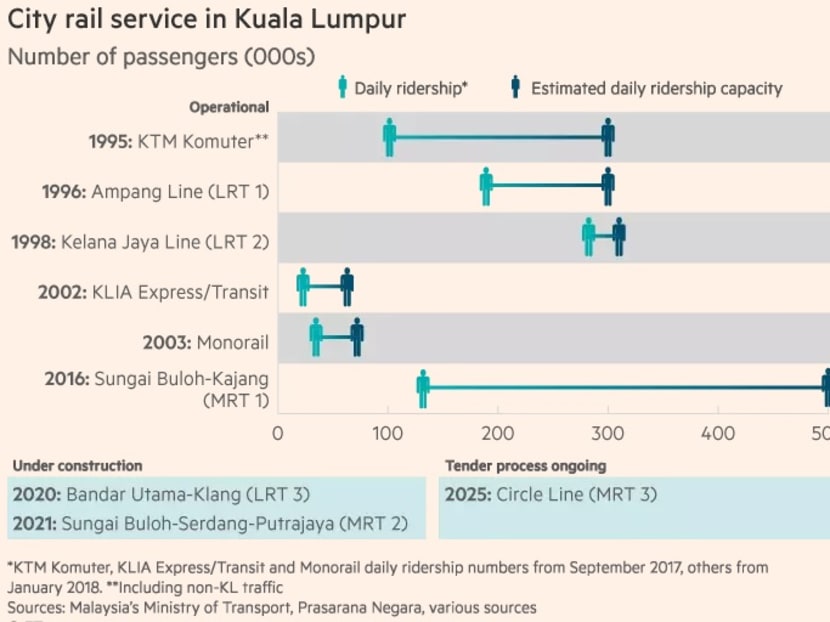

While older rail lines from the 1990s are operating very close to capacity during rush hours, the newest line — the Sungai Buloh-Kajang (SBK) mass rapid transit, opened in December 2016 — is being underused.

Costing Rm23 billion (S$7.8 billion) to build, excluding land and consulting costs, the line has a maximum capacity of 400,000-500,000 people per day.

The operator of the line had said it would carry 150,000 passengers daily by mid-2017, but the January 2018 numbers show just 132,000 passengers a day.

The SBK line has the capacity to take cars off the road; in September last year, the latest figures available for all lines, 15-20 per cent of KL’s rail passengers used it.

However, the slower-than-expected growth in passenger numbers means that the new line is currently no match for congestion.

Half of FT’s Kuala Lumpur survey respondents said traffic would get worse this year despite better rail connections, versus only 16 per cent who said the situation would improve.

Kuala Lumpur does not have the worst traffic problem in Asean. The gridlock in Jakarta and Manila can be particularly soul-wrenching.

Nevertheless, the World Bank estimated that road congestion in and around Kuala Lumpur reduced Malaysia’s 2014 gross domestic product by between 1.1 per cent and 2.2 per cent. But congestion cannot be tackled by trains alone.

The government has proposed a congestion charge but it is unclear if or when it will be implemented. Singapore has an electronic road pricing system, and until recently Jakarta enforced tight restrictions on single-occupancy vehicles entering the city centre.

The slow rise in passenger numbers also means the rail system will need more government support and non-ticket revenue. It is difficult for Malaysian public transport services, especially urban rail services, to be profitable from ticket sales alone; the light rail transit lines had to be bailed out by the government after the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Nevertheless, financial sustainability does matter to the Malaysian government. MRT Corporation, a state-owned enterprise that owns the assets of the SBK line, plans to monetise its land along the train tracks to help with construction costs.

Prasarana Malaysia, the operator of the city’s LRT and MRT services, hopes to double non-ticket revenue to 30 per cent by 2020.

Low rider numbers have not discouraged MRT Corporation from laying down more tracks. The company is building a Rm32bn-Rm40bn line linking Kuala Lumpur with Putrajaya, the seat of Malaysia’s government since 1999, with trains expected to start running by 2021.

The company is also rushing out tenders for a circle line in the capital which could cost just as much. Meanwhile, work is also starting on a Rm9 billion Kuala Lumpur-Klang LRT line.

In the southern city of Johor Bahru, the Malaysian and the Singaporean governments recently agreed to extend the Singaporean mass transit system to Malaysia to ease congestion at the border crossing, with a 2024 service start date.

In George Town, in the north, the Penang government intends to build a light rail line, although the tense political ties between the opposition-controlled state and the federal government could jeopardise the plan.

Public transport use in George Town and Johor Baru is lower than in Kuala Lumpur, and lower than the national average (see chart). While the rail extension from Singapore to Johor Baru will be popular with commuters — many Malaysians living in Johor Baru go to school or work in Singapore — the George Town service, if it happens, may be embraced with even less enthusiasm than the new line in the capital, given the smaller and sparser population. FINANCIAL TIMES