The Big Read: Saving Singapore’s endangered species, one 'animal bridge' at a time

SINGAPORE — Making a wildlife crossing “animal ready” from day one was no child’s play for a team from the Mandai Wildlife Group (MWG) .

Months ahead of the opening of the Mandai Wildlife Bridge, a team from Mandai Wildlife Group had taken pains to make sure that it would be ready for animals once the bridge opened. Despite their efforts, the team remained doubtful if animals would use the 140m bridge. However, the animals took to the bridge far quicker than anyone expected.

- Even before the Mandai Wildlife Bridge opened in late 2019, the team behind it had been worried that animals would not take to the bridge

- However, a week before the bridge's official opening, long-tailed macaques were already spotted using it. Wild pigs, rare sambar deers followed suit not long after

- Still, roadkill continues to be an issue, with a critically endangered Sunda pangolin found dead in the area last year

- While eco-bridges help, environmental experts stress the need to go beyond remedial solutions to the issue of habitats being destroyed through development works

- Motorists and the general public need to be better educated when it comes to living alongside animals, they say

SINGAPORE — Making a wildlife crossing “animal ready” from day one was no child’s play for a team from the Mandai Wildlife Group (MWG) .

A year before the 2019 opening of the Mandai Wildlife Bridge, which was partly meant to address roadkill, flood lights pointing towards the forest edges along Mandai Lake Road were installed to discourage animals from crossing the road.

The road, which runs from Mandai Road to the Singapore Zoo and cuts through a part of the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, is a common crossing for animals in the adjacent forest patches.

They include the long-tailed macaques, wild boars and rarer species such as the sambar deers and Sunda pangolins.

The team from MWG also planted the bridge with common tree species found in the area so that animals would be drawn by the familiarity of the vegetation on it several months before its official opening on Dec 6, 2019.

Despite their efforts, the team remained doubtful if animals would use the 140m bridge.

“When we first planted the trees, there were still gaps in between the trees and they hadn’t formed the canopy or looked forest-like. So we thought the animals would be a little bit more wary of such a new landscape,” said Ms Chua Yen Kheng, who oversaw the bridge project as Assistant Vice President of Sustainable Solutions at MWG.

The team was also unsure if the animals would adapt to the “human concept” of bridges, added Mr Lim Zongxian, a wildlife management officer who joined the team three months before the bridge opened in December 2019.

However, the animals took to the bridge far quicker than anyone had expected.

Even a week before its official opening, photos from six camera traps set up along the bridge showed that long-tailed macaques were already using it.

And within the first week of its opening, larger mammals such as wild pigs and sambar deers were spotted using the bridge.

“We were searching online for things that would encourage the animals to use the bridge but upon seeing the footage – we were like, ‘Eh, wah! They started to use the bridge so early!Mr Lim Zongxian, a wildlife management officer with Mandai Wildlife Group”

Their presence was well ahead of the six-month time frame that the team had expected for the first of these animals to set foot on the bridge.

Spotting these animals in photos from the camera traps brought relief to the team, said Mr Lim.

“We were searching online for things that would encourage the animals to use the bridge but upon seeing the footage – we were like, ‘Eh, wah! They started to use the bridge so early!’” he said.

Mr Lim, 30, said that the animals may have adapted earlier than expected to the bridge as those in the area would already be used to human disturbance, given the ongoing construction work in the vicinity.

Such animals could be more curious or less deterred by new changes to the environment, explaining their early adoption of the bridge, he said.

His boss, Ms Chua, 46, was especially glad that the two animals spotted early on the camera were sambar deer and wild pigs — two animals that the bridge had specifically targeted.

Consultations with the nature community had shown that these animals would commonly dash across Mandai Lake Road in the morning, risking themselves to motorists.

Two years on, nearly 70 species of wildlife have been spotted using the animal-only bridge located near the Singapore Zoo.

Besides the sambar deer, which was estimated in 2010 to number fewer than 20 in Singapore, Sunda scops owl, common-palm civet, the large-tailed nightjar (a bird), and the lesser short-nosed fruit bat have also been captured on the camera traps.

Saplings of Glochidion obscurum, a recently discovered and locally threatened tree species, have also been found growing on the bridge as a result of animal dispersal — a positive sign of natural regeneration of flora, the wildlife group said in an update of the bridge earlier this month.

Occasionally, a less welcomed species has been spotted on the bridge: Humans.

Ms Chua said that the team has detected "a few" occurrences of trespassing in mid-2020, with members of public likely to have strayed from nearby publicly accessible trails.

Once such instances were detected, the team conducted checks at the bridge's potential entry points and locks on its gates were replaced with studier ones as precaution. Signs were also put up to alert trespassers.

The bridge, which took about two years to be constructed, is part of the first phase of development for a new nature attraction in Mandai.

The attraction by MWG, which is expected to be completed by 2024 following delays due to the Covid-19 pandemic, will house five parks: Rainforest Park, Bird Park (which will be relocated from Jurong), the existing Singapore Zoo, Night Safari and River Wonders. A new eco-resort, allowing visitors to stay close to nature, is also part of the overall project.

The wildlife bridge is intended to reduce the risk of animal roadkill along Mandai Lake Road, which was built about six decades ago.

A TASK 'BOTH BORING AND EXCITING'

The job of monitoring the bridge and the buffer areas leading to the Central Catchment Nature Reserve on both sides of the road is “both boring and exciting”, said Mr Lim.

His job involves scouring through about 30,000 to 50,000 photos a year to identify and record details of the animals in pictures.

Processing the data from the photos, which are taken by more than 40 camera traps placed on the bridge and the buffer zone, can take up to 900 working hours a year, he said.

While trawling through the photos can be boring, there is a sense of excitement when they offer glimpses of interesting behaviour by the animals.

These include watching small mousedeer munching on African tulips a third of their size near the bridge, and watching “very cute and small” Bambi-like baby fawns grow up over months through the photos, said Mr Lim.

“Sometimes, we can even identify certain individual animals up to a period of time,” he added.

His team of four has also named male sambar deers, which have been spotted using the bridge almost every night, based on the shape of their antlers.

One is named “Mutant” for its oddly shaped antlers while another has been christened “Mr Maleficent” in reference to a 2014 film of a similar name where the protagonist, a villainous fairy, sports a headdress with twisted horns.

There are also curious long-tailed macaques which try to pry the cameras that are strapped to the trees, triggering multiple close-up photos of them.

While the bridge has become a common crossing for some animals, the team is still waiting with bated breath for their next milestone — the crossing of the critically endangered Sunda pangolin and lesser mousedeer.

“They are always teasing us around the boundary of the bridge,” said Mr Lim.

The team has placed log piles along the bridge in the hope that they will draw these “shyer” animals to step foot.

As the vegetation on the bridge has yet to fully grow and provide a continuous forest cover, there are open gaps that make these animals more cautious of using the bridge.

The log piles will serve as stepping stones or shelter for these animals when they navigate the bridge, said Mr Lim.

Outside of the bridge, the team will also restore degraded vegetation patches along the buffer zone.

BRINGING FORESTS TOGETHER

Ecological bridges (eco-bridges) such as the one in Mandai help to reconnect patches of forest that have been spliced by development and more than 9,000 land-km of roads in highly urbanised Singapore.

Apart from providing animals with safe passage, such bridges also allow them to forage for food and expand their genetic pool by finding mates from different locations.

The first such bridge here is the 62-m long Eco-Link@BKE.

Opened in 2013 and managed by the National Parks Board (NParks), the Eco-Link@BKE connects Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and Central Catchment Nature Reserve over the Bukit Timah Expressway (BKE).

The bridge was built after the construction of the BKE in 1986 divided central forests in Singapore into Bukit Timah Nature Reserve on one side and Central Catchment Nature Reserve on the other.

In response to TODAY’s queries, NParks said that since its completion, populations of various native animals have been recorded on Eco-Link@BKE.

They include the Slender squirrel, Sunda pangolin, lesser mousedeer and Changeable Hawk-Eagle.

“Apart from setting up more eco-bridges, the nature groups also suggested exploring other types of linkages to aid animals, such as culverts for underground connectivity, rope bridges for primates and land bridges for land crossings.”

WHAT NATURE GROUPS SAY

While members of the nature community have welcomed the addition of the Mandai bridge, they called for more studies to evaluate its long-term effectiveness.

“It’s positive that animals are using the bridge. That’s definitely beyond question,” said Ms Anbarasi Boopal, the co-chief executive officer of Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres).

She added that the number of species sighted on the bridge did not come as a surprise as the Mandai area is rich in biodiversity.

Dr Andie Ang, a primate researcher, said that reports on the number of species using the Mandai bridge meant that they could have been saved from becoming roadkill.

Studies on how frequently the animals use the bridge and the number of roadkill over time can help to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the bridge, she said.

Apart from setting up more eco-bridges, the nature groups also suggested exploring other types of linkages to aid animals, such as culverts for underground connectivity, rope bridges for primates and land bridges for land crossings.

In addition to the existing Mandai bridge, Dr Vilma D'Rozario, the co-director of the Singapore Wildcat Action Group (Swag), proposed that peninsulas in Upper Seletar Reservoir near Mandai be connected by land bridges to help animals cross them.

Apart from eco-bridges, Ms Anbarasi said that specially designed culverts for wildlife would be useful for animals which prefer travelling underground. Pythons, smaller mammals and even pangolins currently rely on the connectivity offered by large canals and pipes around Singapore, she said.

NParks said that it has installed underground culverts in areas such as Old Upper Thomson Road for small mammals, such as pangolins and porcupines, and larger mammals such as the lesser mousedeer.

The agency has also installed aerial rope bridges across carriageways to facilitate the safe movement of tree-residing animals, such as the Raffles’ banded langurs. The latter have been spotted to use the rope bridge above Old Upper Thomson Road to move between Thomson Nature Park and Central Catchment Nature Reserve.

Nature groups which spoke to TODAY reiterated the need to enhance connectivity between more green patches through eco-links including bridges.

Dr Ho Hua Chew of Nature Society (Singapore) flagged several areas requiring eco-bridges: These include across Upper Thomson Road, between Thomson Nature Park and the forest patch north of Tagore Drive, and also across Mandai Road between the Central Catchment Nature Reserve and its sliced-off patch to the north of the road.

He also recommended that two major eco-links be installed, with one at the Kranji Expressway between Tengah forest and the areas around Old Chua Chu Kang Road and another linking up Tengah forest to Bukit Gombak across two roads there.

These links would facilitate the dispersal of wildlife along the planned Tengah Nature Way between the Western Water Catchment area and Bukit Timah Nature Reserve.

But in building these bridges, Dr Ang said it is important for different agencies in the same development vicinity to communicate with each other to ensure that the crossings will be used by animals.

“If an eco-bridge is built to link up forest A and forest B but the latter is going to be cleared for development, the animals will have nowhere to go,” she said.

She added that eco-bridges should be seen as a valuable but complementary tool to restore habitat connectivity, especially if trees and lianas are also planted to establish natural connectivity.

Ms Chua of MWG described eco-bridges as an "opportunity" and “investment”.

“You can’t just build it wherever you like because it is also an investment. You want to build it in a place where the chances of the bridge being used are high.”

REDUCING ROADKILL

Despite the advantages of eco-bridges, it is not foolproof in eliminating roadkill.

Ms Chua of Mandai Wildlife Group recalled how the team was disappointed to learn that a Sunda pangolin had ended up as roadkill along Mandai Lake Road in March last year.

“It was quite upsetting because it was one year after the bridge was set up. We had been anticipating for the Sunda pangolin to cross the bridge but then, it appeared on the road,” she said.

The investigations into the incident were inconclusive, showing that the pangolin could have tried to enter from Mandai Road, which cannot be fenced up as it is not under MWG.

It could also have come from the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, climbed over the fence into the Night Safari and walked out to the road, said Ms Chua.

Even before the eco-bridge opened, MWG had put up fencing along Mandai Lake Road and closed the road to motorists from 1.30am to 6am daily to reduce roadkill. Speed humps, signages and rope bridges for long-tailed macaques and squirrels to use were also installed.

Despite such efforts, seven roadkill incidents were reported between January 2020 and December 2021 within 500m of Mandai Road, which lies about 350 north of the eco-bridge.

Besides the pangolin, other animals that died included the Malayan colugo, the long-tailed macaque, wild pig, red-tailed pipe snake, the Asian house rat and Javan myna.

When asked about the number of roadkill incidents, Ms Chua said that rather than relying on such figures, the effectiveness of anti-roadkill efforts should be based on the type of species that is affected.

“In this area, because it is around the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, there is a high chance of roadkill. Occasionally, we have monitor lizards (as roadkill) because they are able to climb over the fence. Snakes and rats too," she said.

“So when people talk about the number of roadkill, you really need to think deeper. Our fences cannot keep out birds, monitor lizards, snakes but we see a reduction in other animals like mammals. The pangolin was a one-off.”

NParks told TODAY that through its feedback system, it has recorded an average of three roadkill incidents per month islandwide in the past six months. The incidents involved wildlife such as macaques and wild boars.

Specific to the area around Eco-Link@BKE, the statutory board had registered pangolin roadkill of an average of about two per year from 1994 to March 2014, to just one between April 2014 and January 2022.

It has also recorded an average of one roadkill incident involving other wildlife, such as macaques and wild boars, around the area between 2015 and 2022.

The agency said it is looking to install more barriers and guide fences along the highway and in forested patches around the area to guide animals towards the bridge and reduce roadkill.

Statistics compiled by Acres, on the other hand, showed a steady increase in animals that had died at the hands of motorists in the last five years islandwide.

According to its figures, the number of roadkill more than doubled, from 93 in 2016 to 194 in 2021.

There were sharp increases across the board from 2020 to last year for reptiles, birds, mammals and pangolins, although the numbers for primates remained similar.

“The animals are forced to cross little pathways that people are on to get to their homes. The animals exposed (to humans) risk becoming roadkill.Ms Anbarasi Boopal, co-chief executive officer of Animal Concerns Research and Education Society”

Ms Anbarasi said that the increase could partly be due to the fact that Acres has been including roadkill reported by others in the nature community from 2020, on top of calls to its hotlines as well as greater awareness among the public that led them to report such incidents.

Moreover, initiatives to green Singapore, such as tree-planting, building of nature trails and park connectors had brought animals into greater contact with people.

“The animals are forced to cross little pathways that people are on to get to their homes. The animals exposed (to humans) risk becoming roadkill,” said Ms Anbarasi.

She also highlighted how some animals such as macaques had become conditioned to come out to the roads to wait for food, due to motorists illegally feeding wildlife.

“They expect the car to stop and feed them, but they end up becoming roadkill,” she said.

Common hotspots flagged by the nature community include areas flanked by forested areas such as Rifle Range Road, Upper Thomson Road, BKE, Mandai Road, Mandai Lake Road, Dairy Farm Road, Neo Tiew Road, Lim Chu Kang Road and Jalan Bahar Road.

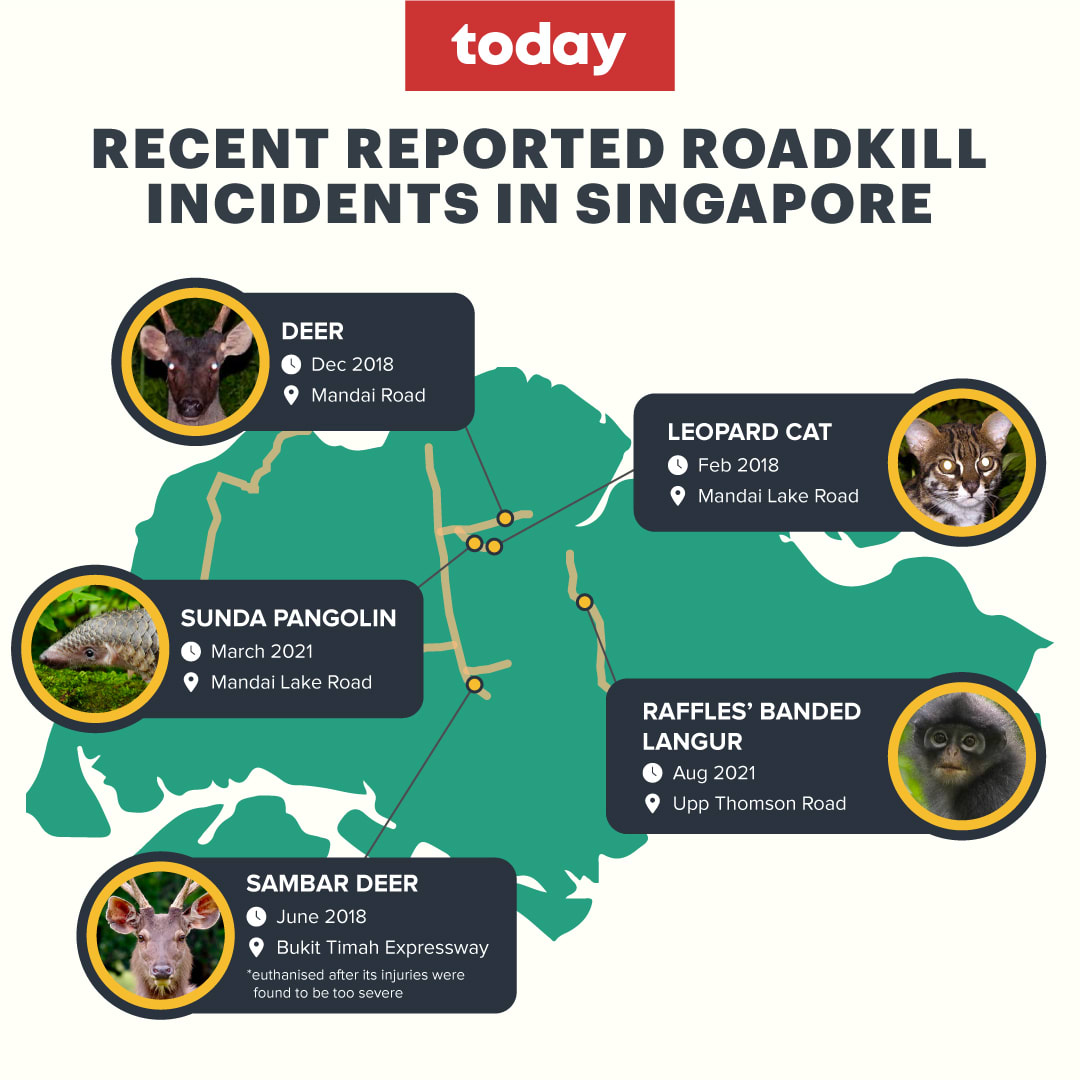

Among the more prominent deaths that have hit the news include the death of a leopard cat in 2018 in Mandai. There are fewer than 50 of these cats left in Singapore and its surrounding islands, including fewer than 20 on the mainland.

A deer had also died after colliding with a motorcyclist along Mandai Road the same year.

A Raffles’ banded langur was also killed in Upper Thomson Road in August last year. There are only about 70 of these critically endangered monkeys left in Singapore.

“(People) drive fast both on highways as well as on narrow roads. They just have to stop driving fast if they are near a nature reserve.Dr Vilma D'Rozario, co-director of the Singapore Wildcat Action Group”

EDUCATING MOTORISTS

Besides the lack of connectivity in some of the roadkill hotspots, animals continue to wander onto roads due to other reasons, said environmentalists.

For one thing, the eco-bridges themselves may not be attractive to certain types of animals.

Dr Ang, who is president of the Jane Goodall Institute (Singapore), said that arboreal animals which live in trees such as langurs, slow lorises and civets that are not comfortable travelling on the ground may find it challenging to get on a bridge if there is not enough tree canopy leading up to the structure.

Likening it to jaywalking, Ms Anbarasi said that not all animals may go up to the bridge to make the crossing if there are not enough measures such as fences to funnel them there.

But a common problem pointed out by nature groups is the lack of education among motorists themselves, who are not mindful of the need to slow down when driving into areas with wildlife.

“People drive fast, and they drive fast both on highways as well as on narrow roads. They just have to stop driving fast if they are near a nature reserve,” said Dr D'Rozario.

She recommended that speed limits be lowered at roadkill hotspots. For instance, the speed limit at Rifle Range Road could be reduced to 20 km per hour, below the current default of 50km per hour, she said.

Also, measures to get drivers to reduce their speeds near sensitive areas can be imposed such as through road humps or the Roadway Animal Detection System (Rads), she said.

The system detects wildlife approaching the road using video analytics and alerts motorists to slow down via a flashing sign.

NParks told TODAY that it will be extending Rads to Rifle Range Road, which lies between the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, and the upcoming Rifle Range Nature Park. The system was originally implemented at Old Upper Thomson Road in 2019 and was found to be effective, said NParks.

GOING BEYOND REMEDIAL MEASURES

Ultimately, environmentalists stressed the need to go beyond remedial measures.

Said Dr Ho of Nature Society: “More and more developments are going on and gaps are increasing. In a way, we are playing catch up, but we are lagging far behind to fill the existing gaps and more gaps keep coming up.”

To sustain Singapore’s biodiversity, the basic problem of development would have to be addressed, he added.

To this end, the “first important principle” is to preserve existing stretches, belts and patches of forests that are left in Singapore. The preservation target should approach the United Nations Convention of Biological Diversity's benchmark of 17 per cent for terrestrial nature conservation.

However, the authorities have been reluctant about preserving green spaces on dry land which is more suitable for development, said Dr Ho.

He noted that although the authorities have said that there are no immediate plans to develop Clementi forest, after a public petition early last year, it still remains classified for residential use.

Similarly, it is unclear if secondary forests such as Windsor Nature Park which are buffer areas for forested nature reserves will be preserved in the long-term, he said.

Despite massive development in the city-state, environmentalists acknowledged that the authorities have made efforts to attract wildlife and rebuild habitats. These include intensifying greenery with native trees and shrubs as part of NParks’ rewilding plan, as well as the aim to plant more than a million trees by 2030.

Ms Anbarasi of Acres noted that such efforts have paid off. For instance, hornbills have repopulated Singapore with help from conservation efforts by NParks, and wild animals such as otters are adapting to the urban habitat.

'CAN'T BE NEGOTIATING WITH A MONKEY'

But while Singapore has been successful in attracting nature, there is still “a long way to go” before Singaporeans learn to coexist with nature, said Ms Anbarasi.

She cited the example of a school student who had pleaded with a monkey that had snatched his school bag to return it. The incident which was captured on video had gone viral on social media last week.

While the boy’s pleas were non-aggressive, Ms Anbarasi said that people have to be more aware.

“We cannot be negotiating with a monkey. It would be a completely different conversation today if the monkey had turned aggressive and scratched the boy,” she added.

She hoped that there would be more awareness, especially among young children, to know how to prevent their belongings from being snatched, and to not try to take their items back from a monkey. They also need to understand why the monkey was sighted in the vicinity in this instance.

“We still have a long way to go in terms of embracing all wildlife and sharing space, even with animals that cause a little bit of inconvenience that we want to get rid of,” she said.

Despite Acres’ public education efforts, Ms Anbarasi said that animals are still “paying the price” for people’s lack of wildlife awareness and etiquette when encountering animals. Animals are forced to relocate or be even euthanised for coming into contact with humans.

Striking a hopeful tone, Dr Ang said that with more people being exposed to Singapore’s biodiversity during the Covid-19 pandemic, public sentiment has become more positive towards the country’s natural heritage and people are more engaged in discourse about the environment.

“Wild pigs and monkeys are part of nature and our ecosystem, just like pangolins and otters are.Dr Andie Ang, president of the Jane Goodall Institute (Singapore)”

She cited how public consultation had contributed to the development plans for Dover forest last year.

The Government had announced last July that part of the forest would be set aside for housing and another for a nature park following public outcry over the forest being earmarked for residential development.

However, public interest in wildlife remained selective, said Dr Ang.

“Wild pigs and monkeys are part of nature and our ecosystem, just like pangolins and otters are,” she said.

To be a biophilic state, where people have a deep-rooted sense of respect, appreciation and love for nature, people will “need to know what nature is, and understand nature as it is”.

Different people and different sectors have a role to play in shaping public education and helping Singapore, which has long strived to blend nature with urban living, to become a biophilic state.

She said: “It is still a distance, but we are getting there.”