The Big Read in short: Online petitions galore and what this means for the Govt

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at how people in Singapore are increasingly turning to online petitions, and how the Government — which has traditionally not taken these petitions very seriously due to their procedural shortcomings — should respond in this new environment. This is a shortened version of the full feature.

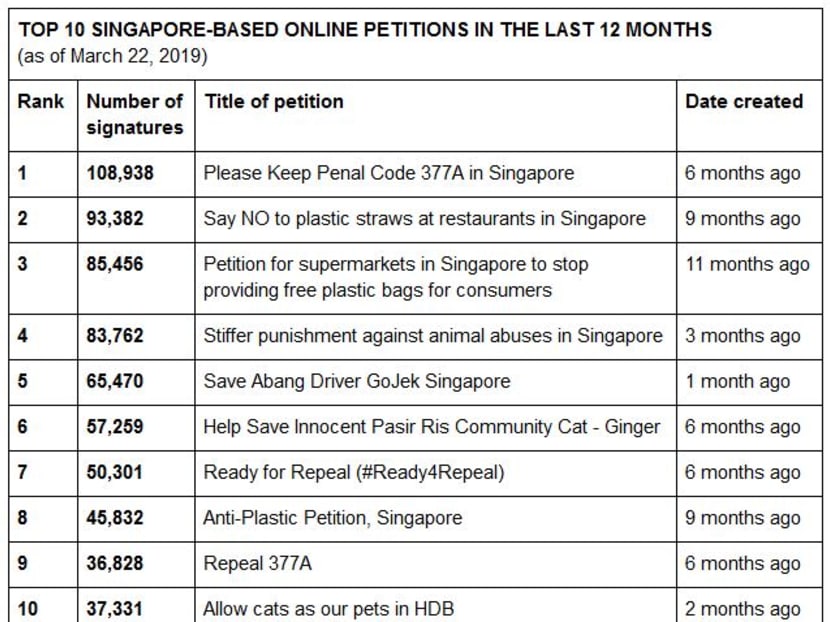

Online petitions here have generally gained significant traction in the past few years, with recent petitions garnering increasingly large numbers of signatures.

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at how people in Singapore are increasingly turning to online petitions, and how the Government — which has traditionally not taken these petitions very seriously due to their procedural shortcomings — should respond in this new environment. This is a shortened version of the full feature, which can be found here.

SINGAPORE — The proliferation of petition websites — which offer online users a one-stop and anonymous platform to solicit collective action — and Singaporeans’ growing readiness to use them have given rise to several questions: How should online petitions factor into policymaking, if at all? How should the Government deal with these public appeals, which make up public feedback yet could be susceptible to abuse and manipulation?

While several Members of Parliament (MPs) and experts interviewed by TODAY pointed out the dangers of allowing policies to be swayed by online petitions, which are fraught with procedural shortcomings, some noted that it is a legitimate form of public feedback which should not be discounted entirely.

Online petitions here have generally gained significant traction in the past few years, with recent petitions on popular sites such as Change.org, GoPetition and iPetitions garnering increasingly large numbers of signatures.

While only some 40 petitions emerged in 2016, 2017 saw more than 100, followed by more than 150 petitions last year.

In the first three months of this year alone, Singaporeans had already created about 60 petitions — a stark contrast to a decade ago when TODAY counted only 11 petitions for the whole of 2009.

GOVT'S POSITION

In response to TODAY's queries, the Office of the Clerk of Parliament said parliamentary rules dictate that it only considers petitions with signatures that are dated and handwritten to ensure that they are not duplicated. These have to be accompanied by the signatory’s name and address. Also, the original copy of the petition printed on paper has to be submitted.

Petitions must also be “respectful in language” and “specific as to the nature of the relief sought”, the spokesman said.

“These procedural requirements help to ensure that a petition presented to Parliament is an authentic request from real and distinct individuals and is not abusive in nature,” he added. While it does not consider online petitions, MPs can raise them by filing a parliamentary question or proposing a motion for debate in the House, he noted.

Earlier this month, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) raised “security concerns” and cancelled the concert of Swedish black metal band Watain — a day after a 19,000-strong petition calling for its ban emerged. Nevertheless, Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam made clear that the petition "per se did not influence the decision”.

The viewpoints of senior clerics, MPs, and “people in the community” were also taken into consideration, he added.

In response to TODAY’s queries on the Government’s position on online petitions, an MHA spokesperson said that it generally remains “cautious” about treating petition as a reliable feedback mechanism “for obvious reasons”.

Noting that the Government “does not rely solely on one channel” to ascertain public sentiments, she said: “Public sentiments is one of many factors we take into consideration when drafting policies. This can come through public consultation, individual emails, or other feedback channels such as Reach (the Government’s feedback unit).”

Read also

MONEY TALKS LOUDER

The advent of the Internet may have facilitated the collection of signatures but it does come at a price. The hosting sites support online petition for “free”, but solicit money from the petitions’ supporters.

Change.org, where most Singaporeans host their petitions on, is one such site. Change.org spokesman David Barre did not respond directly to concerns about the platform's methods, but he reiterated that the funds are used to boost the number of people who would see a particular petition. “The more support a petition has, the more likely it is to reach their decision maker,” he added.

WHAT MPS AND EXPERTS SAY

While some have criticised online petitions as a form of “slackivism” that should not be taken seriously, Dr Carol Soon, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies, calls them “a form of political expression and engagement (that) should not be discounted”.

People’s civic engagement is usually “not static” as it evolves with their life stages and social networks, she added.

Dr Soon also said that online petitions are based on what social movement researchers call “the logic of numbers”, so inevitably, the bigger the number, the more likely the cause would attract the attention of those whom the petitioners are targeting, such as the Government.

Read also

“To a certain extent, online petitions is a numbers game,” she said. “We have seen how online petitions which accumulate many signatures within a short period of time attract the policymakers’ attention.”

While petitions may raise important issues that warrant a response, some MPs still find it hard to take them seriously, considering the high-profile case of a 2016 online petition for a second Brexit referendum that was found to be rigged with some 77,000 signatures.

There are also concerns that there are no mechanisms to limit signatories of petitions on local issues to Singaporeans only, and to prevent a signatory from impersonating another person.

Still, Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC MP Teo Ser Luck said that policymakers should not be immediately “sceptical” and should instead “give a listening ear”. “We may not want it to be, but the numbers do give you an indication of the interest in a segment of the public,” he said.

For him, it is about separating the gems from the junk, or issues that “may not be perceived as substantial”. “The Government needs to decide if it (the petition) is real and substantial enough to represent the larger views and critical enough to review or act on it,” Mr Teo said.

Singapore Management University law professor Eugene Tan noted that most petitioners here do not expect concrete results, as they recognise how the Government operates.

Still, it is "desirable enough" for them to be able to argue and show that there is a certain depth of support for their cause.

“It is a form of self help by putting into the public domain one’s stand on a matter of public interest. Further, it conveys the narrative that ‘I am not the only one feeling this way; that the view is shared by hundreds or thousands of people’," he said.