Lab-grown and plant-based meat can help us move towards a more sustainable food system

With the March launch of Impossible Foods’ plant-based meat in Singapore and this month’s announcement of S$144 million research funding in food innovation under the Government's Research, Innovation and Enterprise 2020 plan, Singapore has further established itself as a leader in shaping the food system of the future.

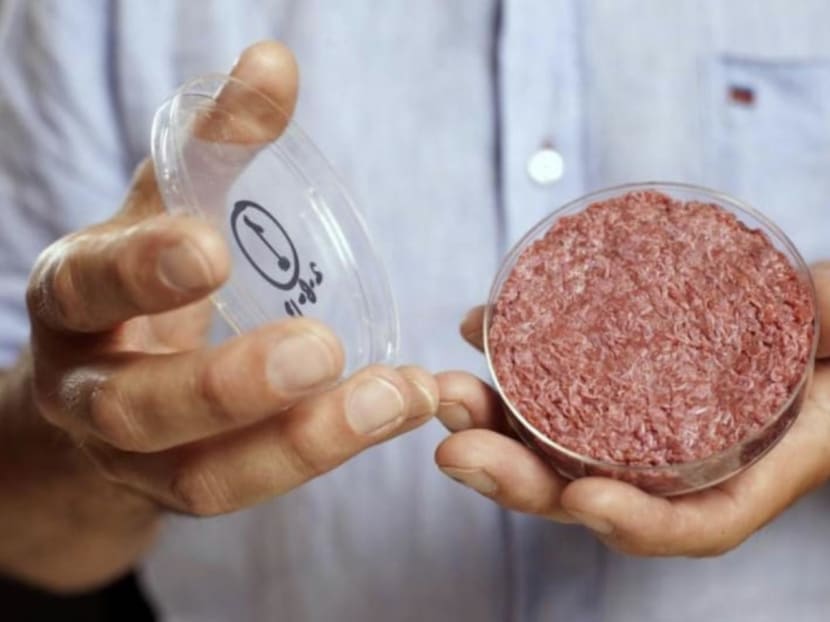

The world's first lab-grown beef burger, cultured from cattle stem cells, is shown in London in 2013.

With the March launch of Impossible Foods’ plant-based meat in Singapore and this month’s announcement of S$144 million research funding in food innovation under the Government's Research, Innovation and Enterprise 2020 plan, Singapore has further established itself as a leader in shaping the food system of the future.

This new research plan includes funding for cell-based meat, and is in line with Singapore’s previous investments in alternative proteins, including Temasek Holdings’ stake in Impossible Foods.

The recent sea change in public and private interest towards meat alternatives as well as the popularity of plant-based meats are an encouraging indicator of a larger transformation taking place in our food system.

I believe the combined forces of technological innovation, far-sighted investment decisions, and conscious consumption are leading us towards a not-too-distant future in which animal agriculture is obsolete.

While the environmental costs and food security concerns surrounding animal agriculture are increasingly publicised, the industry’s significant contribution to urgent public health issues like antibiotics resistance, zoonotic disease, and chronic lifestyle-related illness also make this transition crucial to our future well-being.

According to the European Food Safety Authority, about 70 per cent of the new diseases that have affected humans over the past 10 years have originated from animals or products of animal origin.

There is also growing scientific evidence that implicates rising consumption of meat and animal products as a primary driver of chronic yet preventable lifestyle-related illness and death.

Medical researchers like Dr Michael Greger and Dr T. Colin Campbell have consistently demonstrated the potential for whole food plant-based diets to prevent and in some cases reverse many of these chronic illnesses, particularly cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of deaths worldwide.

While these health challenges might seem daunting, they also signal an exciting opportunity to help address some of the most pressing concerns we face by transforming our food system.

Many individuals are already initiating this change due to health, environmental, or ethical concerns, with Nielsen reporting that 39 per cent of US consumers are adding more plant-based foods to their diets.

Some may dismiss these changes as another food fad, but the production efficiencies of plant-based foods give them a long-term market advantage over animal foods.

A lifecycle analysis of the plant-based Impossible Burger found that it requires only 13 per cent of the water, 4 per cent of the land, and generates 11 per cent of the emissions of a conventional beef burger.

READ ALSO:

The effect of these efficiencies on cost competition could become especially pronounced as climate change and environmental degradation constrain the availability of freshwater and arable land.

While the current price of the Impossible Burger is closer to premium-grade rather than mass-market meat, its trial in select Burger King locations in the US at a US$1 premium over normal burgers is yet another step towards price parity and mass-market distribution.

At a presentation at the National University of Singapore last month which I attended, Impossible Foods founder and CEO Pat Brown predicted its prices will lower considerably over the next year as production scale increases.

At the same time, it is reasonable to doubt that the world will go entirely plant-based any time soon, given the current global trend towards increased meat consumption, especially with the growth in the middle class in developing markets.

This is where a second technological advancement comes into play: clean meat.

Also known as “cell-based meat” or “lab-grown meat”, this new production method grows animal tissue by taking a small sample of cells from an animal, and providing them nutrients and a clean environment to grow that is free from the antibiotics, disease, hormones, and bacterial contaminants that are often present in conventional production.

READ ALSO:

Enormous quantities of clean meat can be grown from a sesame-seed-sized sample taken harmlessly from an animal.

Although clean meat does not offer all the nutritional benefits of plant-based foods, it will still help address the concerns of antibiotic resistance and zoonotic disease while providing ecological advantages comparable to a plant-based production system.

The enticing economics and efficiency of clean meat production may enable it to supersede conventional production once the technology matures.

Clean meat can be grown in two to three weeks rather than years, and requires only three calories of feedstock rather than 23 to produce one calorie of beef.

Instead of growing an entire animal, this technology enables us to grow only the tissue desired for consumption and utilise nutrients to grow tissue rather than having to power the many biological processes that support a farm animal during her life.

While clean meat production is not yet at scale and the technology is still maturing, some experts predict clean meat will be cost-competitive with grass-fed meats within the next three to five years, compete with all meat products in about a decade, and eventually become less expensive than conventionally-produced meats.

When the first lab-grown burger was developed in 2013, the cost per kg was US$2.4 million, but by 2017 this cost dropped to US$5,000 per kg, and is now about US$11 for a patty.

This is what Dr Kelvin Ng, head of strategic innovation at Singapore’s Bioprocessing Technology Institute which has started trials on producing clean meat, told The Straits Times in a recent interview.

At a food-tech conference in Singapore last November, I was fortunate enough to get a taste of this future when I sampled a clean meat chicken nugget by JUST, which is scheduled to be available in some restaurants this year.

Another strong signal that this is the future direction of our food system is that the biggest meat companies in the world like Tyson Foods and Cargill are investing in plant-based and clean meat technologies, with many other food companies like Nestlé incorporating plant-based foods into their product strategies through acquisition or investment.

In addition to the ecological, economic, food security, and public health benefits, this shift towards a plant-based and clean meat food system will lead to a cultural change that could fundamentally alter our relationship with nonhuman life from one characterised by exploitation to compassion.

As Jacy Reese explains in his book “The End of Animal Farming”, human history has seen a steady expansion of humanity’s moral circle along many different dimensions including race, gender, and sexual orientation.

With the development of a more humane food system, the next chapter in this march of progress could see the inclusion of nonhuman species as well.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Peter Lewis, a vegan and a graduate of Yale-NUS College, does business development for Open Sesame, the food startup incubator and enterprise business of At-Sunrice GlobalChef Academy.