Can Singapore and rest of South-east Asia rise to the challenge of surging seas?

Why are sea levels rising and how will it affect the region and Singapore? And what can we do about it?

Accelerating arctic melting has revealed uncharted islands in Greenland and threatened to raise sea levels all over the world. If all the ice in Greenland melts, it would raise sea levels by 7m. Antarctica has enough water to raise sea levels by 65m.

The Government announced in March that it will start a National Sea Level Programme this year to bring together research expertise and better understand how rising sea levels will impact Singapore.

On Wednesday (July 17), Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli said that the Government will set aside S$10 million in funding for the programme over the next five years and set up a new office to strengthen Singapore’s capabilities in climate science.

Why are sea levels rising and how will it affect the region and Singapore? And what can we do about it?

While all coastal cities will be affected by rising sea levels, Asian cities will be hit much harder than others given their population, economic activity and landmass.

Furthermore, many of the processes that control sea-level rise are amplified in Asia. As a result, about four out of every five people impacted by sea-level rise by 2050 will live in East or South-east Asia.

WHAT CAUSES SEA LEVELS TO RISE?

Sea-level rise is one of the more certain impacts of human-induced global warming. The world is getting warmer because of the release of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere.

The last five years are the warmest ever, according to the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration which has been tracking global heat for 139 years. The Earth's average global temperature has risen by 1 degrees Celsius since the 1880s.

If you think this is not a lot, then you are wrong. Twenty thousand years ago, the ice was up to three kilometres thick in North America. The average global temperature had only to change 5 degrees Celsius to eliminate all of this ice and raise sea levels by 120 metres.

That change in temperature took 10,000 years, eliminating almost all the glacial ice mass between the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, creating the conditions where human culture, civilization, and economy could thrive.

Earlier this month, the Centre for Climate Research Singapore predicated that the nation could also face days of 40 degrees Celsius as early as in 2045. This was followed by a warning from a group of climate scientists from Crowther Lab that Singapore is among cities that will face “unprecedented” climate shifts by 2050.

Global warming affects sea level in two ways. About a third of the rise in sea levels since the beginning of the 20th century comes from thermal expansion — from the fact that water grows in volume as it warms. The rest comes from the melting of ice on land.

So far the melting of ice has been mostly mountain glaciers, but the big concern for the future is the giant ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. If all the ice in Greenland melts, it would raise sea levels by 7m.

Antarctica has enough water to raise sea levels by 65m. You only need to melt a few per cent of the Antarctic ice sheet to cause devastating impact.

Satellite-based measurements of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets show that the melting is accelerating.

For example, Greenland's glaciers went from dumping only about 51 billion tons of ice into the ocean between 1980 and 1990, to losing 286 billion tons between 2010 and 2018. The result is that out of nearly 14 millimetres of sea-level rise caused by Greenland since 1972, half of it had occurred in just the last eight years.

Since at least the start of the 20th century, the average global sea level has been rising. Between 1900 and 2016, the sea level rose by 16 to 21 centimetres.

But the amount of sea-level rise will vary from place to place. Regional sea-level trends include land subsidence or uplift due to geological processes, the influence of ocean currents and gravity.

At a local scale the amount of groundwater withdrawal and tidal range variation may be important. The sum of global, regional and local trends leads to certain areas of the Earth having far greater rates of sea-level rise. One of these hotspots is Singapore.

Future sea-level rise will generate hazards for coastal populations, economies and infrastructure of South-east Asia with over 450 million people living in low-elevation coastal zones. Twelve nations have more than 10 million people living on land at risk from sea-level rise, including China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia and Japan.

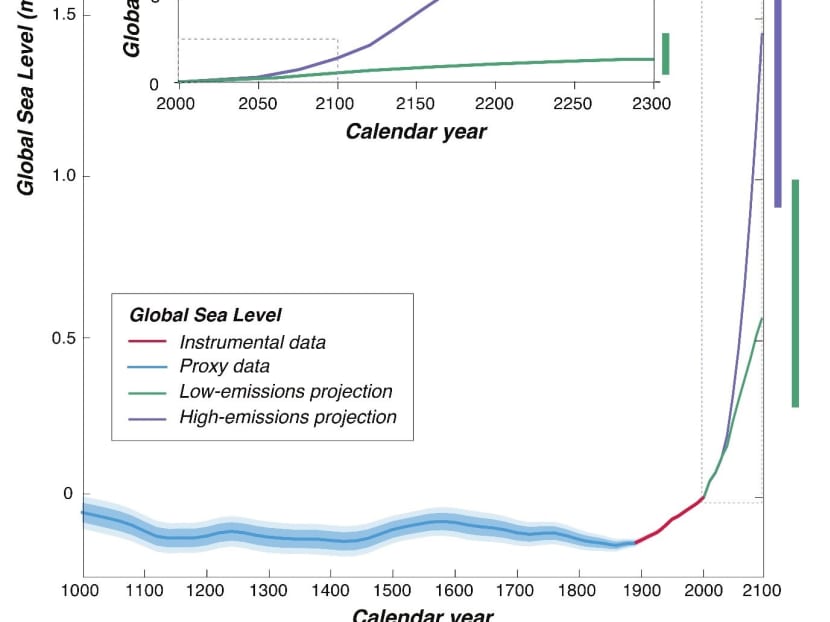

This graph on projected sea levels is combined from a variety of datasets compiled by the author. The low-emission projection is one where commitments to the Paris climate agreement are met, whereas the high-emission projection is based on a business-as-usual scenario.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

We need to identify the potential solutions that could reduce flood risk from sea-level rise in ways that support the long‐term resilience and sustainability of communities and the environment, and that reduce the economic costs and risks associated with flood damage.

There are three options.

First, we can defend against floods with infrastructure that keeps tidal waters at bay, such as bulkheads, pumps, and mangrove restorations.

Second, we can also elevate existing houses and build new ones on stilts. Changi Airport, for example, is building Terminal 5 at 5.5m above sea level to protect against rising seas.

We can further think about engineering advances that will enable Singapore buildings to "float". These buildings could be semi-submersible, with foundations on the sea bed, like oil rigs, or floating structures that are kept stable by mooring systems, which are already used for homes in Ijburg, Amsterdam.

Third, those living in cities that could be severely affected by rising seas could relocate altogether. Indeed, we cannot rule out the possibility of such mass migrations in the decades ahead.

Ultimately, the best way to mitigate rising sea levels is to slow down climate change by implementing the commitments laid out in the Paris Agreement.

If every country meets its commitment, the Earth will warm about 2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century compared with its pre-industrial average.

It is believed that somewhere between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius of temperature rise lies a tipping point where the Antarctic ice sheet will slip into rapid and shattering collapse, with catastrophic consequences for cities around the world.

Whether or not we meet the Paris Agreement depends on how sustainably we can live.

Fortunately, in the last 15 years, attitudes across the world toward the environment have shifted. Where once there was ignorance, inattention, and disbelief about environmental problems, now there is concern, a modicum of political will, and a growing understanding of the causes of environmental problems and their solutions.

Policymakers, scientists, and the thinking public now have a will to find solutions — be they engineering, financial, or institutional — that can be brought to bear to solve climate change.

I am commonly asked what an individual can do to live sustainably and combat climate change. We must make sacrifices and break our habits.

Every political, business and lifestyle decision needs to be taken with an understanding of how it affects the environment. For example, we could pose a very simple question “will this action add to or reduce greenhouse gas emissions?”

If it will increase them, then don’t do it, or offset it. The decisions we make today and in the coming years will affect life on Earth.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Professor Benjamin Horton is Chair of the Asian School of the Environment, Nanyang Technological University.