Uproar in China over Vogue’s depiction of Chinese model: Who’s wrong, who’s over sensitive?

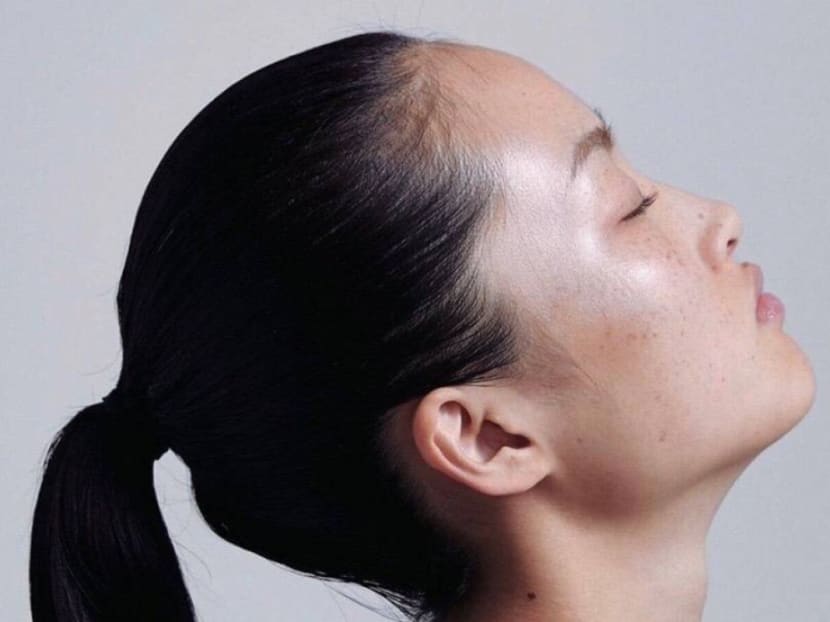

Earlier this month, American fashion magazine Vogue came under fire in China because of an Instagram photo it put out featuring Chinese model Gao Qizhen, a textile design major student in London.

Earlier this month, American fashion magazine Vogue came under fire in China because of an Instagram photo it put out featuring Chinese model Gao Qizhen, a textile design major student in London.

Critics say the image exaggerated her wide-set eyes, fine eyebrows and indiscernible nose bridge, and take issue with Vogue’s caption that she “brings a kind of singular appeal”.

Before long, the original Instagram as well as the related Weibo post were flooded with angry comments, like, “You’re giving people a weird idea of what Chinese people look like”. Some accused Vogue of “purposely uglifying Chinese people” and even being racist.

As a Chinese female journalist currently working in the United States, I am well aware of the cultural gap between the Chinese and westerners around this debate.

To many Chinese social media users, Ms Gao apparently falls short of their idea of being a beauty. In recent decades, with rising commercialism, the definition of beauty in China has converged around doe-eyed, pale-skinned Barbie looks and slender figures.

Today, almost all of the most popular Chinese female pop stars share these features.

The popularity of plastic surgeries and widespread use of mobile phone apps like BeautyCam also contribute to the increasingly similar representation of beauty: big eyes, slim face, sharp chins as well as pale, smooth skin.

Women who don’t look this way are subject to be labelled as “ugly”, or worse, even get bullied on social media. This time with Ms Gao, it was just a lot harsher.

Read also

- The beauty industry aims to be more inclusive

- Beauty industry chalks up most complaints in 2018; watchdog flags ugly practices

The Vogue saga came hot on the heels of the “freckle-gate” of Spanish cosmetics brand Zara, which was lambasted for featuring a Chinese model with freckles clearly visible in its ad campaign “Beauty is Here”.

“You spent such an effort searching for a model with freckles, like finding a needle in a haystack, how hard you must have worked on this”, one comment in Chinese read.

It is notable that such reactions towards Vogue and Zara have come amidst rising nationalist sentiments in China.

Over the past few years, the combination of victim mentality rooted in past mistreatment by Western powers and jingoistic national pride as a result of recent economic miracles has turned many into overzealous vigilantes.

They often see evil motives in those they believe to have “hurt Chinese people’s feelings” and demand apologies across the world.

Escalating what is an aesthetic debate into one on “patriotism” however, is not only unnecessary, but self-defeating. The narrow definition of beauty and the hurtful words said to these Chinese models in essence reveal how hard some have fallen for the eurocentric standard of good looks, and could lead to internalised racism.

But at the same time, I can understand where some of the Chinese netizens who took offence to Vogue were coming from.

While Vogue may have wanted to promote diversity in this case, some critics do have legitimate questions as to why Western fashion brands tend to have a fixation on the perpetual “exotic” stereotypes of “Asian-ness” and not recognise the diversity among the Asian people.

The image of Asian women that has been portrayed on the international fashion stage is still relatively unitary rather than diverse, such as wide-set eyes and flat nose bridges.

The tendency of always depicting a stereotypical appearance of an ethnic group is insensitive when the intention is to be inclusive.

At the same time, the attention that Ms Gao has drawn speaks of the fact that Asian women are still disproportionately underrepresented on the international fashion stage.

This ironically explains simultaneously why Vogue is making efforts to showcase Asians on its diversity-promoting campaign and why some Asian women feel offended when they realise that as they are finally represented, they are still more or less viewed through the lens of orientalism.

Yet I won’t call it discrimination or racism, let alone “uglifying China”.

In sum, Vogue did not cover itself in glory with the way it presented a Chinese model. At the same time, some of the reactions in China are overboard.

Ms Gao is confident, natural and cute, but there are many other styles of beauty in Chinese women. Of course we may not agree on what is beauty, but the best way to bridge differences in opinion it to listen to each other.

And what did Ms Gao, who is with London-based modelling firm Anti-Agency, make of the saga?

“Anti is a word that applies as a negative thing in some fields, but in terms of fashion and modeling I think it challenges the norms of beauty and looks," she says.

Hopefully, “anti” here will also apply to “anti-stereotype” and “anti-victim-mentality”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Audrey Jiajia Li has been a broadcast journalist for more than 10 years and is also a non-fiction writer whose columns have appeared in various international media.