The Big Read in short: Deciphering Malaysia's political future in the wake of a polarised youth vote

SINGAPORE — After several days of being kept on tenterhooks following an inconclusive general election (GE), a sense of cautious optimism finally pervaded many young Malaysians after a unity government was formed on Nov 24, with reformist opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim as the prime minister.

While the majority of urban youth voters whom TODAY spoke to in the wake of the hustings had been optimistic about Pakatan Harapan taking the reins of government, political observers said these youngsters represent only one half of the youth story for GE2022.

Each week, TODAY’s long-running Big Read series delves into the trends and issues that matter. This week, we look at the impact of the youth vote on Malaysia's 15th General Election and what the results mean for the country's political landscape. This is a shortened version of the full feature, which can be found here.

- The results of the recent Malaysia General Election reflect an electorate that is more divided than ever, and the youth vote was no different

- While a majority of urban young voters cheer Pakatan Harapan leader Anwar Ibrahim’s appointment as prime minister, the news was met with disappointment by rural youths

- They had hoped that Perikatan Nasional would form the new government, with Malay and Muslim concerns getting top priority

- The split in Malaysia's youth vote, despite youths being a symbol of progress in other countries, is not surprising, say observers

- The lack of formal political education, the effective use of social media by some political parties, as well as the impact of Covid-19 have left youth in Malaysia more ideologically divided than ever

SINGAPORE — After days of being kept on tenterhooks following an inconclusive General Election (GE), a sense of cautious optimism finally pervaded many young Malaysians after a unity government was formed on Nov 24, with reformist opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim as the prime minister.

Ms Tiffany Yeo, 27, a firm supporter of the new government led by Mr Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, said: “I’m relieved… if the result had gone another way, I think there’s not much hope left for many of us.”

The magazine writer, who voted in Petra Jaya in Sarawak, was referring to the possibility of the other rival coalition, led by former prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, coming to power instead.

Like many urban youth voters whom TODAY spoke to, Ms Yeo made no secret of the fact that she had voted for Mr Anwar’s PH coalition, which she believes holds more progressive and needs-based values, compared to other political parties that had campaigned based on racial lines.

Now that the 75-year-old Mr Anwar — whose decades-long journey to the top had been filled with twists and turns, as well as jail terms — is in the driver’s seat, Ms Teo said that she can breathe easy.

But another young voter, business consultant Kaz Mansor from Muar, Johor, is keeping any optimism in check for the time being, despite being cheered by the formation of a unity government.

While the 28-year-old hopes that Malaysia can move forward as a nation after a tumultuous two years, he is afraid that history may repeat itself, with the country falling into another round of political turmoil, as it did shortly after the previous GE in 2018.

“I’m just afraid that these political leaders will do something like the Sheraton Move again, and the whole political drama will never end,” said Mr Mansor.

The Sheraton Move occurred in early 2020, less than two years after PH took power, when a faction within the coalition defected to form Perikatan Nasional (PN), and establish a new government with Mr Muhyiddin as prime minister.

The preference by Ms Yeo and Mr Mansor for a PH-led government dovetailed with the view held by some analysts that young, urban voters tend to support Mr Anwar’s coalition.

As the country headed into its 15th GE last month, the needs and wants of this demographic had come under scrutiny, after a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 added millions of new voters to the electoral rolls.

In a commentary published by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) earlier this year, political science professor Meredith Weiss from the University at Albany wrote that it is natural to think of youth as liberals championing for various causes, and this had led to speculation that the “expansion of the suffrage could push Malaysian politics sharply leftward”.

The reality, however, is “far more complicated”, she said.

While Malaysian youths have a long history of activism for left-wing or “progressive causes”, she noted that the 2018 GE also uncovered a significant share of young voters who backed the Islamist Parti Islam SeMalaysia (PAS) instead.

Indeed, while the majority of urban youth voters whom TODAY spoke to in the wake of the hustings had been optimistic about PH taking the reins of government, political observers said these youngsters represent only one half of the youth story for GE2022.

The other part is crafted by those who tend to vote more conservatively — mainly the Malay rural youth, whom experts said had voted largely for PN, based on anecdotal evidence.

At the time of writing, there has been no data publicly released by the Election Commission of Malaysia or studies by think tanks looking at the voting patterns according to demographics such as age and race.

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT THE YOUTH VOTE

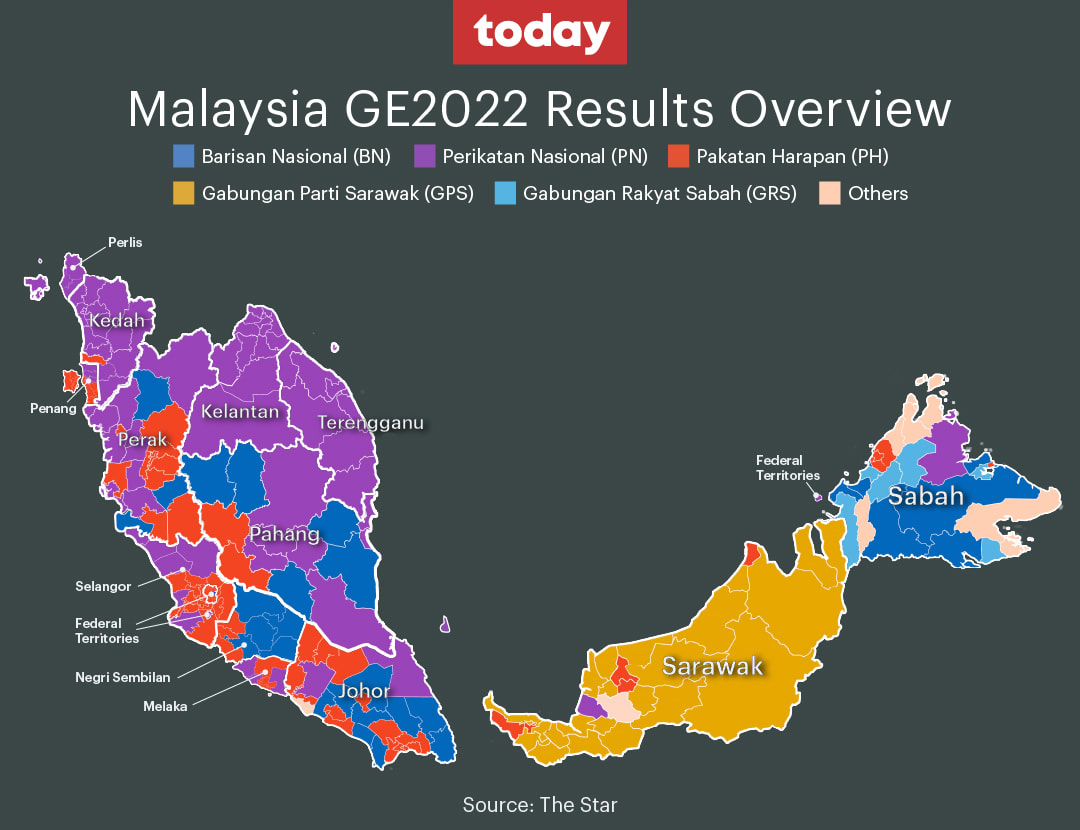

Of the 222 parliamentary seats up for grabs in the election, PH won 82 seats, the most among all the coalitions, with Mr Muhyiddin’s PN taking 73 seats.

The incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition — led by the once-powerful United Malays National Organisation (Umno) — won 30 seats, its poorest-ever showing in the elections.

Instead of the youth vote being a straightforward case of left-leaning tendencies — as some pundits had thought — preliminary assessments suggested that the vote had been divided between conservative and progressive camps.

The split very much mirrored the share of votes gained by PN and PH, both on the opposite ends of the political spectrum.

Dr Oh Ei Sun, a senior fellow with Singapore’s Institute of International Affairs, said that though the official analysis of the voting data has not been published yet, it is “safe to say youth vote did impact the results”.

“Those voting for the conservative versus the progressive ends of the political spectrum are at least comparable,” he said.

In the Malaysian context, the progressive camp refers to those who focus on governance and anti-corruption, and shun racism and religious bigotry. The conservative camp embraces more ethnic Malay-Muslim views.

Elected Members of Parliament (MPs) across the political divide, who were privy to the raw voting figures in their respective constituencies, largely agreed with Dr Oh.

PH’s Adam Adli told TODAY that within the urban polling stations within his constituency of Hang Tuah Jaya in Melaka, there were more youth votes for him and his party.

The 33-year-old said that he was privy to the number of votes he received in each polling station where the votes were divided roughly according to age groups. The younger age groups in urban areas made up a larger proportion of his votes compared to the others, he said.

However, he said that this was “not necessarily true” in rural areas within his constituency, where he saw a significantly lower proportion of younger voters.

Similar youth voting patterns were observed for PN candidate Wan Ahmad Fayhsal Wan Ahmad Kamal.

Mr Wan Fayhsal, 35, emerged victorious in Machang, Kelantan, which is relatively more rural, and has a higher Malay demographic.

He said over a phone interview that he and his coalition had won a “massive swing of new votes” — based on the numbers presented to him at each polling station, he said that PN had swept virtually all of the youth votes.

The big divide in the youth vote has contributed to what experts have described as a “new stage in Malaysian politics” that is more fractured than ever.

Indeed, Islamist PAS, a PN member, is now the biggest single party in Parliament with 49 seats, while PH’s component party, the Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party, is second-largest with 40 seats.

WHAT YOUNG RURAL VOTERS SAY

Young rural voters told TODAY that they had voted for parties linked to PN, such as PAS, largely due to a perceived lack of alternatives — the other coalitions were either marred by corruption scandals or were not seen as champions of the Malay race.

PAS supporter Nik Hafizuddin, 20, believes the Islamist party and its coalition PN are free from the corruption scandals that have dogged BN, and have a clear focus on preserving Malay rights and Islamic values — issues which he feels have been neglected by Mr Anwar's PH coalition.

The polytechnic student who had voted in Kuala Krai, Kelantan, said that he knows PAS is “clean” as he had been watching campaign material on social media featuring the party's candidates and had fact-checked their claims online.

“I also voted PAS because they uphold Malay and Muslim rights more compared to other candidates or parties who denigrate Muslim rights,” he said.

The need to protect Malay interests and Islamic values was evident among young PN supporters.

Civil servant Zaim Irsyad, 38, said that he had not always been a PAS supporter, having been “on the fence” since he came from Selangor, which has been a PH-dominated state.

Over the last three elections, however, he began to see the need for a strong government that is both free of corruption and stands up for Malay rights, which is why he began voting for PAS. While he used to vote in Selangor, he now votes in Pasir Puteh, Kelantan.

He clarified that those who support PAS should not be seen as doing it solely for the “Islamic cause”.

“I studied in a (secular) school, but I still vote for PAS. Among Malays, there are many who do not have a background in Islamic schools, but they still think of the survival of the Malay race and Islam," he said.

FACTORS BEHIND POLARISED YOUTH VOTE

Political observers highlighted several factors behind the progressive-conservative split in the youth vote.

- Social Media

Social media was key in polarising young voters, especially in helping PN do exceptionally well among young Malay voters, said the observers.

A key difference from the 2018 GE was that the conservative parties during this year’s polls had much greater success in rallying support from young voters through social media.

Dr Bridget Welsh, an analyst from the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, said that PN’s success was partly due to the clever use of TikTok and social media influencers to spread its messages.

“The effective framing of the PN campaign (meant that) many were not even aware that PAS was part of PN, they voted against Umno and in favour of less corruption and stability,” she said.

During the hustings, several TikTok posts, mostly from the PN camp, had gone viral.

Most notable was a fan account featuring PN leader Muhyiddin dancing to the hit rap song “Swipe”, which racked up four million views in a single day.

Aside from fun and quirky content online, there were also ones that promoted divisions along racial and religious lines, with the potential to stoke ill-will among young voters, said the observers.

For instance, a portion of a speech by Mr Muhyiddin during his campaign was shared on TikTok, with the PN leader making unsubstantiated claims that the rival PH alliance was colluding with “groups of Jews and Christians” whose aim was to convert Malay Muslims.

SIIA’s Dr Oh said that he observed that “quite a number” of young voters had been “enamoured by the TikTok propaganda generated by the conservative camp”.

“The TikTok videos appeared to have employed somewhat alluring influencers to emphasise voting for PN such that race and religion could be preserved and promoted,” he said. “This could be particularly alluring to youngsters who were long inculcated with racialist and religious sentiments, and are at times lonely and bored.”

Referring to claims that some of the pro-PN content could be seen as racially and religiously divisive, Mr Wan Fayhsal, the elected PN MP for Machang, said: “Most of the statements have been misquoted, taken out of context, with the accusations against us unfounded.”

“When people talk about how religion and race affect politics, it’s a fact and not a fiction, we are not going to be apologetic about it.Wan Ahmad Fayhsal Wan Ahmad Kamal, an elected Perikatan Nasional MP for Machang, Kelantan”

He said that as much as the “liberals” believe that race and religion should not be raised, these issues are part and parcel of the “social fabric” of Malaysian society and should be addressed.

“When people talk about how religion and race affect politics, it’s a fact and not a fiction, we are not going to be apologetic about it,” he said.

- Political education

Malaysia’s educational system does not equip its students with sufficient political knowledge, which means that they are often left to find out about politics on their own, said the observers interviewed.

This has become more evident in GE2022, compared to the elections in 2018, with approximately 1.4 million voters between the age of 18 and 20 being able to vote this year. This was the first time that Malaysians of this age group — many of whom would still be studying — could vote.

Dr Serina Rahman, a lecturer at the department of Southeast Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, said: “Ideally, there should be national education in the sense that youth learn about what it means to vote, campaign and serve the people.

“But in reality, this 'education' is biased and written by the winners… so there is no guarantee that there is no misinformation being taught.”

The lack of political education among the average Malaysian has prompted non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to kickstart initiatives to educate youths on the democratic process.

One such NGO is Undi18, which had successfully advocated for the minimum voting age to be lowered from 21 to 18.

Its co-founder and education director Qyira Yusri said that the group has been trying to better educate young voters so that they make informed decisions, but knows it can only do so much.

“We have been consistent in calling out the education system for being not adaptive… and resistant to changes,” she said. “This leaves young people with no choice, but to get their political information through social media, such as through the usage of TikTok.”

- Impact of Covid-19

Another key difference between previous elections and GE2022 is the impact of Covid-19, which had led to political and economic uncertainties for Malaysians.

The turmoil of the past two years had led to frustrations among the electorate, especially the young, said observers.

Mr Kevin Zhang, a senior research officer in the Malaysia Studies Programme at the Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said that those aged between 18 and 24 were especially impacted, with many in that age group having just started out their careers.

“If you look at the median income numbers and unemployment numbers, those below 24, it has created a lot of discontent among Malay youths for BN,” he said.

He added that the BN-led post-pandemic recovery for this age group has been the slowest compared to other age groups.

“Essentially, the pay gap between those in the 18-24 compared to those in mid- 30s is large and it doesn’t seem that the gap has narrowed, or it has even widened,” said Mr Zhang.

POTENTIAL REPERCUSSIONS OF POLARISED YOUTH

With the youth vote more split than ever, the outlook for the nation is a gloomy one, some observers argued.

Dr Oh said that the youth voting patterns signal a “rather grim” future, as it has become clear that instead of being more progressive like the youth of other societies, a large proportion appear to be “even more conservative than their elders”.

“It represents an unexpected dusk in Malaysian politics, as from now on, religious discourse and race supremacy will be front and centre in Malaysian political development,” he added.

Looking ahead, one can also expect all parties to contest the social media space more keenly, taking a page from gains by PAS and PN during GE 2022.

Undi18’s Ms Qyira said: “I think in this election, PN had gotten ahead of everyone else. If (parties) want to control the narrative, it’s about understanding the medium, and how they want to communicate their message.”

Overall, the trends affecting the youth vote in GE2022 will be the ones that Malaysia will continue to face in the next few decades.

“Why would you assume that the younger voters will be less racial or less religious minded? The schools that they’ve been going to in the last 10 to 15 years have been the same, so there shouldn’t be any difference.Professor James Chin from the Asian Studies department at the University of Tasmania”

Professor James Chin from the Asian Studies department at the University of Tasmania said that the assumption that younger generations will tend to be more progressive cannot be applied to the Malaysian context.

“Why would you assume that the younger voters will be less racial or less religious minded? The schools that they’ve been going to in the last 10 to 15 years have been the same, so there shouldn’t be any difference,” he said.