Gen Z faces different forms of stress, may be more anxious, depressed than others before them, says IMH CEO

SINGAPORE — Even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, researchers have predicted that people from Generation Z (Gen Z) are poised to be one of the most stressed, anxious and depressed generations of all time.

Dr Daniel Fung, head of the Institute of Mental Health, said that he has observed an uptrend in teenagers with emotional dysregulation, who may display destructive behaviour either towards themselves or towards things around them.

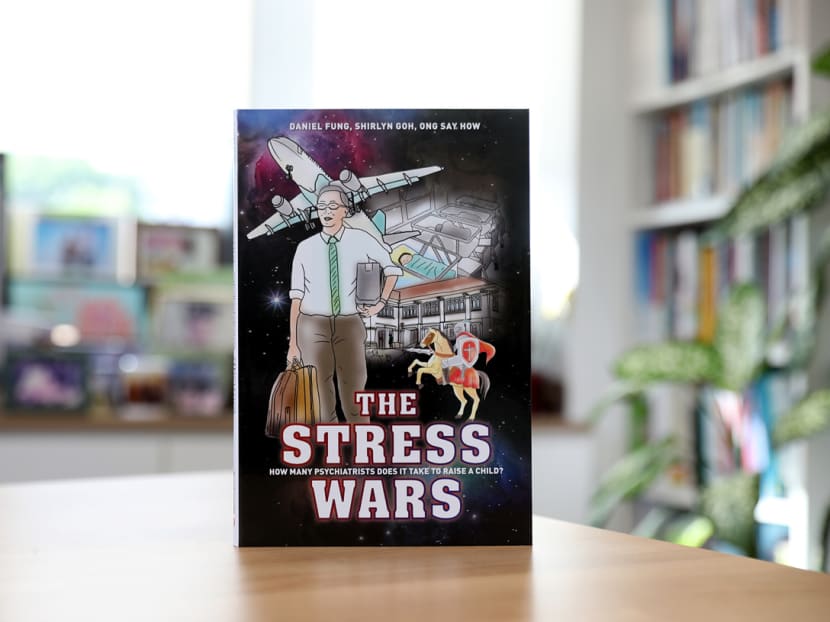

- The Institute of Mental Health recently launched a graphic novel titled The Stress Wars

- It chronicles Singapore’s 50-year journey of child mental health services

- The book also provides parenting tips on how to raise children who are well-prepared for life

- Veteran child psychiatrist Daniel Fung gave some insights into the mental health issues among the young today

- He urged parents to set time aside for their children during their early years

SINGAPORE — Even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, researchers have predicted that people from Generation Z (Gen Z) are poised to be one of the most stressed, anxious and depressed generations of all time. This is the demographic group that come after the millennials. They are born after 1995 and are now in their teens and early 20s.

Although Gen Zers are the most digitally connected generation, they are less likely to report good or excellent mental health compared with the previous generations.

The ongoing global health crisis appears to have taken an even heavier mental toll on this age group.

For example, a recent study that looked at more than 1,000 Gen Zers aged 18 to 24 in the Asia-Pacific region, including Singapore, found that they faced the highest levels of stress compared with other generations.

They were also the most likely age group to report symptoms of depression during the pandemic, based on a survey conducted by Sandpiper Communications, a communications agency with offices in Singapore, Australia, China and Hong Kong.

Are Gen Zers really doomed to be one of the most anxious and depressed generations?

It is possible, veteran child psychiatrist Daniel Fung said. The chief executive officer of the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) said that this may happen if they do not learn to manage stress, which is one of the factors that increase the risk of mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety.

However, it is not just the prevalence of modern-day stress and the ongoing pandemic that is worrying.

“I think it also has to do with the fact that we haven’t really equipped people to handle (stress) well,” Dr Fung said.

The 55-year-old recently co-authored a graphic novel published by IMH titled, The Stress Wars: How Many Psychiatrists Does It Take To Raise A Child?. The other authors are Dr Ong Say How, senior consultant psychiatrist at IMH, and Ms Shirlyn Goh, a senior lecturer with Nanyang Polytechnic.

Stress among youth in Singapore is one of the topics covered in the book, along with parenting strategies.

PEOPLE ARE MORE ISOLATED THAN EVER

Dr Fung said that children growing up in today’s modern, urbanised environment face very different forms of stress compared with the previous generations.

Singapore is one of the most densely populated countries in the world.

“While living density has increased, we also experience a lot of isolation. We may not be physically distanced but we are socially distanced. Of course, the pandemic does not help,” he said.

Even within homes, Dr Fung said that there is a certain degree of isolation because family members are each in “some sort of social media bubble”.

“That is not good because parents’ relationships with their children are the basis for their future and development. We are not relating to one another the way we should,” he added.

‘WE NEED MENTAL HEALTH LITERACY’

Dr Fung, who has five children aged 21 to 28 and who just became a grandfather, started his career in IMH in 1994.

His research interests include anxiety and disruptive behaviour, and he is the president of the International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions.

He said that stress, in itself, is not necessarily a bad thing.

In manageable doses, short-term stress can push one to perform better.

However, when it becomes chronic, long-standing, unexpected or uncontrolled, that is when stress can contribute to mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.

“If there are any preventable mental illnesses, that would be anxiety and depression. These are the two (mental illnesses) that are linked to environmental factors like stress,” he said.

“So, what we can do is to work on teaching people to manage stress, maybe not so much reduce it. Having coping skills, what I call mental health literacy, is important.”

TYPE OF CASES SEEN

In the new book he co-authored, Singapore’s 50-year journey of child mental health services is chronicled, starting with the Child Guidance Clinic that was first set up in 1970 to better understand and manage mental health issues among the young here.

IMH now runs two Child Guidance Clinics located at Buangkok Green Medical Park and the Health Promotion Board on the grounds of the Singapore General Hospital. They are for children and teenagers aged 18 and below who are facing emotional and behavioral problems.

The number of new cases seen at these clinics are around 2,400 a year and have remained more or less stable in recent years.

However, Dr Fung observed that some cases seen here have changed over time.

He has observed an uptrend in teenagers with emotional dysregulation, who may display destructive behaviour either towards themselves — for example, those with suicidal tendencies — or towards things around them.

Emotional dysregulation is used to describe the inability to control or regulate emotional responses.

“I’ve been seeing cases of young people (who are emotional dysregulated) who thrash up their house. We have always seen such cases in the past but we’re seeing more of them now.”

He said it is hard to pin down a specific cause. It could be due to factors such as poorer stress coping management in teenagers or an issue with parenting style.

THE SPOILT CHILD SYNDROME

Dr Fung has also encountered a number of out-of-control “spoilt” children in recent years.

“Their parents don’t know what to do (with their children). They say they have done everything, given the child everything and the child is out of control,” he said.

A notable case he encountered involved a teenager who was well-behaved in school but was “a monster” at home to the mother and would beat her up.

Dr Fung thinks that a more permissive style of parenting favoured by the new generation of parents might have played a role in the phenomenon.

Permissive parenting, sometimes called indulgent parenting, is a type of parenting style characterised by low demands but high levels of responsiveness towards the child.

While permissive parents can be very warm and loving, they provide few clear guidelines, structure and rules for their children or are inconsistent in enforcing rules.

This style is different from authoritative parenting. While authoritative parents are also warm and responsive to their children, they are relatively “demanding” in that they set limits, rules and enforce standards of behaviour.

Studies have linked permissive parenting to a higher risk of behavioural problems and misconduct in children. They are also less likely to perform well in school.

However, Dr Fung added that parenting is personal and there are also children who turn out well, regardless of the parenting style.

“This is where parents must understand their child and take the child’s individual temperament into consideration. Different children have different needs. Parents should be responsive (to their child) but not demand less of their child. It should be a balance,” he said.

PARENT-CHILD BONDING IN EARLY YEARS

When asked whether he thinks Singapore is an ideal and fun place to raise children, Dr Fung said: “We want Singapore to be the best place to do that. We have created the infrastructure for that. Our social compact, the learning and living spaces are all there, but at the heart of it is the family, and I think that’s where work still needs to be done.”

Emphasising the role that families and parents play in children’s growing-up years, Dr Fung said that the first three years are critical for healthy child development.

Research has shown that the early years of a child’s life, particularly the first three years, are critical for brain development and much depends on the child and parents or significant caregiver forming a loving bond.

Studies, such as those by Dr Martin Teicher from Harvard Medical School in the United States, have found that children who suffer neglect, parental inconsistency and lack of love in their early years may experience impaired growth in the brain that could increase the risk of mental health problems such as depression and anxiety disorders as well as learning and memory impairments.

In the book by IMH, the authors wrote about the importance of the caregiver-child bonding in the upbringing of a child, and provided tips on how parents ought to interact with and respond to their child in a positive manner.

For instance, instead of always saying “no” to the adolescent child, consider saying “yes” but with some conditions, Dr Fung said.

An example is when the teenager asks if he or she could stay out late with friends during the weekend. Parents may agree to that but suggest an acceptable time that the child should be home.

Dr Fung said that setting clear rules and responsibilities within the family when children are young is also important. For example, sharing among siblings, imposing limits on the amount of time spent using gadgets and digital devices and making sure there is a healthy sleep routine. These rules can be adjusted along the way as the child grows.

The Stress Wars, priced at S$22.47, is available at IMH’s e-shop, and on Goguru, Kinokuniya and Amazon online bookstores.