Singapore students with depression, anxiety symptoms miss 24 days of school yearly on average: Study

SINGAPORE — When 19-year-old Fitriah found herself displaying symptoms of depression and getting easily overwhelmed at school, she did not seek professional help or a formal diagnosis due to the high costs involved.

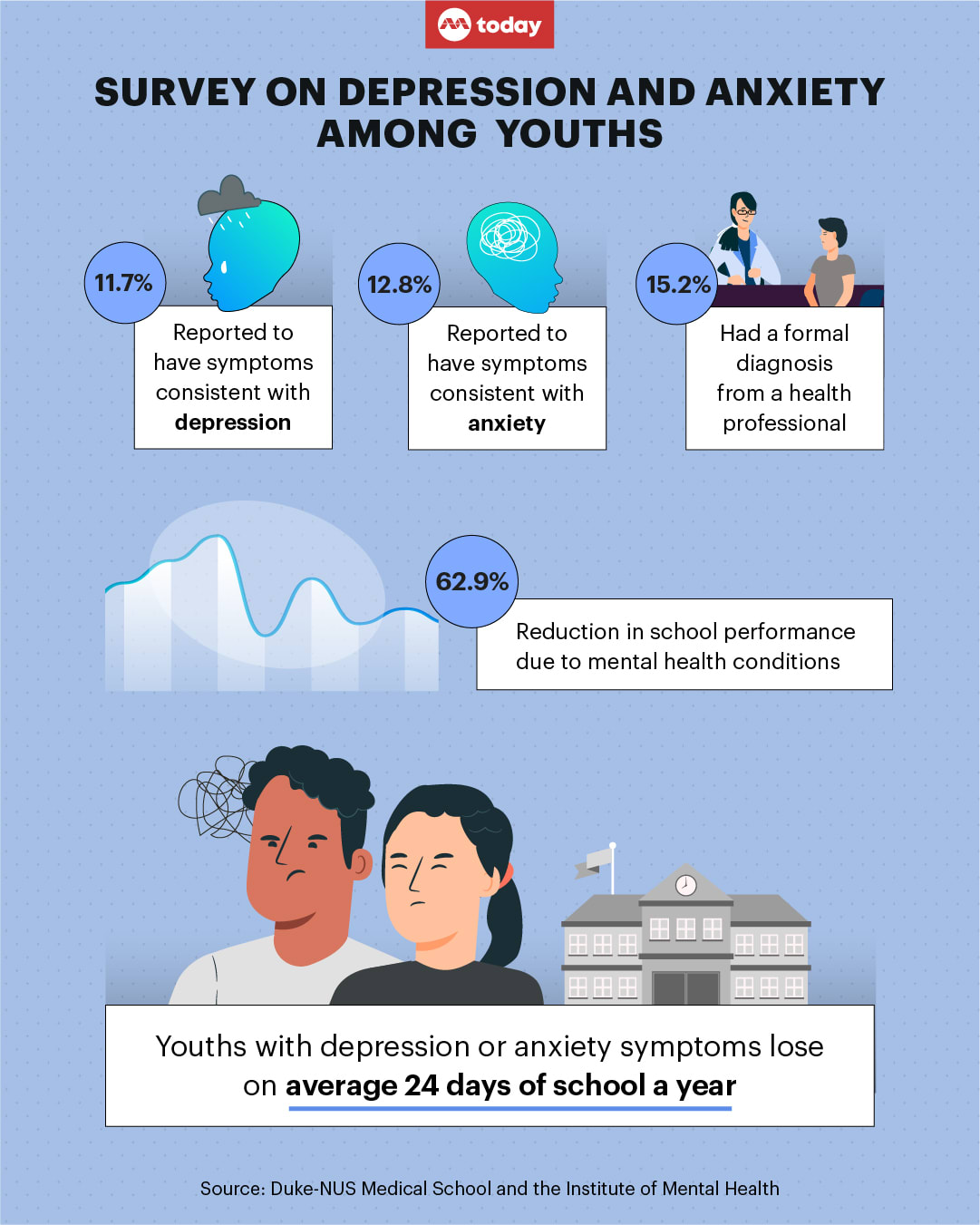

- Depression and anxiety symptoms among Singaporean youth have resulted in them missing an average of 190 hours, or 24 days, of school a year

- The study findings by Duke-NUS Medical School and the Institute of Mental Health was published on May 11

- It also found that more than one in eight, or 13 per cent, missed the equivalent of three months or more of school

- Yet, 84.8 per cent of children with symptoms consistent with depression or anxiety did not have a formal diagnosis from a healthcare provider

- High treatment costs, parental consent, and confidentiality and privacy concerns were deterrents in seeking help, youth and medical workers said

SINGAPORE — When 19-year-old Fitriah found herself displaying symptoms of depression and getting easily overwhelmed at school, she did not seek professional help or a formal diagnosis due to the high costs involved.

Instead, she admitted that she took “mental health days” off school when she needed them, which led to her faking multiple illnesses over the years to cover up her mental health challenges.

The young woman, who wished to be known only as Ms Fitriah, told TODAY that her fragile mental state dragged her down from being a top scorer at school to “flopping horribly”.

“I feel like I’ve wasted so much of my potential academically,” she added.

Her troubled experience is emblematic of the findings of a study by Duke-NUS Medical School and the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) published on May 11.

The study found that depression and anxiety among Singapore youth resulted in them missing an average of 190 hours, or 24 days, of school a year.

But for about one in eight, or 13 per cent, the outcome was even worse because they missed the equivalent of three months or more of school, the survey found.

Researchers from Duke-NUS and IMH surveyed 991 parents, representing 1,515 children and youth aged four to 21, between April and June last year.

The survey found that of the 1,515 participants, 178 (or 11.7 per cent) had symptoms of depression and 194 (or 12.8 per cent) had symptoms of anxiety, with a proportion of them reporting both symptoms.

WHY IT MATTERS

The researchers said there is evidence that the prevalence of anxiety and depression among youth is increasing, which contributes to the high healthcare costs that they face and their poor school performance.

Given significant potential for underreporting, the researchers added that these results reveal concerning numbers of young people here with symptoms consistent with depression and anxiety, many of whom remain untreated.

The results also reveal the short-term problems caused by these symptoms, and hint at longer-term consequences resulting from poor school performance.

These findings should highlight the importance of early intervention among youth facing mental health challenges, the researchers added.

PARENTS SAY CHILDREN WITH DEPRESSION, ANXIETY DO WORSE AT SCHOOL

On average, young people with symptoms consistent with depression or anxiety missed 190 hours of school in the past year, which is equivalent to about 24 days.

In total, nearly four in 10 or 39 per cent of the youth missed the equivalent of one month of school or more, and 13 per cent missed the equivalent of three months of school or more, the study found.

Parents were asked the degree to which the child's depression or anxiety symptoms affected performance at school, on a scale of zero to 10 where 10 indicates that the symptoms completely prevented the child from attending school.

They were also asked to give a similar rating about their child’s performance of regular daily activities.

Among parents who reported that their children had symptoms of depression or anxiety, the average rating they gave to the question about school performance was 6.3 and the average rating for daily activities was 5.8.

Dr Adrian Loh, senior consultant psychiatrist at Promises Healthcare, said that the long-term effects of untreated mental health conditions could include academic and occupational difficulties, such as dropping out of formal schooling or an inability to hold a secure job.

Mr John Shepherd Lim, chief well-being officer of Singapore Counselling Centre, said that leaving mental health conditions untreated had been shown to reduce levels of employment and salary, among other outcomes.

In a media release on Thursday (May 18), the senior author of the study Eric Finkelstein said: “The real effects of untreated mental health conditions among youth will extend well into adulthood when they are less able to obtain rewarding and high-paying jobs due to poor school performance and other challenges resulting from their illness.”

Professor Finkelstein is a health economist from Duke-NUS’ Health Services & Systems Research (HSSR).

Ms Fitriah told TODAY that her inability to find the support system she needed in school had made her condition worse.

“There was some empathy from some teachers but not enough to aid me in the mental health struggles that I faced,” she told TODAY, adding that still having to work on assignments and examinations did not help either.

“I went from a top scorer to a student in the lower rankings and that further increased the weight on my shoulders as well as the guilt that I faced.”

She said that she felt her dwindling mental health in her teenage years played a big role in her academics “flopping horribly”.

HIGH HEALTHCARE COSTS A DETERRENT

Over the past year, 63 per cent of children with symptoms consistent with depression or anxiety visited the emergency department, and 54 per cent were admitted to the hospital, the study found.

Direct healthcare costs due to depression or anxiety averaged S$10,250 a child, with emergency department visits, hospitalisations and diagnostic tests accounting for 43 per cent of these costs.

The survey also found that at the population level, direct healthcare costs for youth with these conditions were estimated to be S$1.2 billion.

Mr Lim from Singapore Counselling Centre said that concerns about affordability, especially for long-term treatment, were among the combinations of reasons why young people do not seek professional help.

TODAY interviewed three young people who said that they had experienced symptoms of a mental health condition such as depression or anxiety, but only one of them had sought help. The other two said that the high costs of therapy and formal treatment were a deterrent. The third eventually stopped counselling, due to the high fees as well.

Ms Qistina Farisha Safrani Mohamed Faizal, 20, who is awaiting enrolment into university, said that she did not seek professional help because she found it unnecessary and “too expensive”.

She thought that it was a phase and she would eventually get over it.

Mr Aqil Nazhan, who is turning 19 this year and awaiting his National Service conscription, said that he had sought help from a counsellor last year, but eventually stopped because he was funding his own counselling sessions, which were too expensive.

He stopped the counselling sessions even though he believed that they had helped him.

“I was also on financial aid, where I paid S$5 a session, but only for the first 10 sessions. Afterwards, it was S$50 a session,” Mr Aqil said, adding that the fee was “a lot” for him.

“Since I'm self-funding, I'm trying to save more than S$50 in case of any emergencies. I'm looking for a job or internship right now, so my process of saving up has been very slow.”

NOT COMFORTABLE TELLING PARENTS

Despite this high level of interaction with the health system, the survey found that 84.8 per cent of young people with symptoms consistent with depression or anxiety did not have a formal diagnosis from a healthcare provider.

This presents a concerning possibility that many young people with mental health conditions in Singapore remain untreated or under-treated, the researchers said.

Counsellors and mental health professionals told TODAY that the perceived stigma over seeking help and support for mental health conditions could deter young people from seeking professional help or an official diagnosis.

Ms Fion Zheng, a professional counsellor at Talk Your Heart Out, noted the “prevalence of the different platforms and channels de-stigmatising and normalising seeking help and support for mental health issues”.

Despite this, "some youths might still worry about being judged or labelled, or facing backlash, especially if their immediate family members or cultural beliefs are not supportive of them seeking help”, she said.

“Youths may also be afraid of confidentiality issues when they seek professional help, in fear that their parents may find out about the issues they face.Mr John Shepherd Lim, chief well-being officer of Singapore Counselling Centre”

Specific to young persons, concerns about confidentiality and privacy, as well as difficulties negotiating conversations with their parents, have also come to the fore.

Mr Lim from Singapore Counselling Centre said: “Youths may also be afraid of confidentiality issues when they seek professional help, in fear that their parents may find out about the issues they face.

“One factor that impedes youth from seeking help would be the age requirement and the need to seek parental consent. Some youths may not feel comfortable disclosing their mental health needs to their parents and hence, may deter them from seeking the help that they need."

Agreeing, Mr Aqil said: “I've never been upfront about my emotions to my family members. Frankly, I get awkward when I have to be vulnerable around them.”

He added that although he would like to seek a referral to IMH for treatment, he has not begun the process.

“I have to be 18 to seek a referral without the need of a parent, and I only turned 18 last November. Since I don't want my mum to know, I have been stalling,” he added.

Responding to queries from TODAY, Prof Finkelstein from Duke-NUS said: “Youths mostly rely on parents for healthcare. For mental health, there is stigma that may prevent them from telling their parents and from their parents taking them to seek care.

"There are also cost considerations, questions about whether it is ‘real’ or just a phase, and concerns about whether treatment would even help.”

Ms Mariya Angelova, a senior counsellor at Sofia Wellness Clinic, said that parents and caregivers have a key role to play in supporting their children on mental health issues.

“Most of the time, what youths really want is for their parents or caregivers to take their concerns seriously and be there to support them along the way.

“If more parents are open to learning about mental health and equipping themselves with knowledge of better communication with their children or even where and how to seek help, a lot of positive changes can happen.”